Sex Doesn’t Sell: Bitchmedia’s Schema for Effective Branding and Financial Viability

Feminist media seek to find niches within Western brand-obsessed markets while simultaneously staying true to feminist values and remaining financially viable. It is a complex juggling act, one where even “big name” magazines like Ms. have historically found themselves struggling financially, attempting, but ultimately failing, to subsist without advertising revenue (Steinem). Feminist media conglomerates, like Ms., Bust, and Bitchmedia, face a conundrum: how can they stay true to their feminist audience while still maintaining financial sustainability given that traditional advertising embraces a sex-sells mentality that directly conflicts with those values? To do so effectively, as I argue Bitchmedia does, requires rhetorical savvy through visual advertising, an advertising averse financial structure, and varied media.

The founding editors of Bitch: Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Andi Zeisler and Lisa Jervis, began with the vision of viewing popular products through a feminist lens. The goal: to give their readers a way to talk back to a sexist mainstream culture. Launched in January 1996, Bitch began as a 501(c)3 feminist, media-critical magazine highlighting “insidious daily sexism that is present in popular culture, proposes alternatives and celebrates pro-woman, pro-feminism popular products” (“About Us”). At first a black and white biannual magazine, Bitch has morphed into a colorful media conglomerate with a quarterly magazine, a blog, two podcasts, a Campus Outreach program, internships, and fellowships. At the time of this writing, it has “an audience of 6 million feminist readers and listeners” broken down into a yearly readership of 47,000; a monthly online visitors average of 500,000; 75,000 email subscribers; 22,000 monthly listeners of the podcasts Popaganda and Backtalk; 10,000 magazine subscribers in 46 countries and all 50 states; and 84 issues to date with issue 85 in the works.

Bitch’s readers tend to be young, educated and progressively minded. Forty-three percent of them are between the ages of 25-34, 78% are urbanites, 49% are college graduates, and 89% identify themselves as politically liberal, progressive, or radical, with almost the entire polled group (85%) claiming to have voted in the previous year’s local, state or federal election (“Sponsorship Kit”). Revenue for the magazine is directly related to the demographics of its readers. Historically, Bitch has warned advertisers that it will not include “imagery or statements that [they] believe may offend readers or that promote organizations, products or opinions that do not match Bitch’s values and mission” (“Ad Specs”). To achieve this goal, Bitch mostly relies on advertisements that are visually bland. Many of them are black and white and resemble business cards; those that are in color are simple in design. It’s Bitch’s use of a few, minimalist advertisements that I analyze in this essay, both quantitatively and rhetorically. I contend that Bitch magazine effectively enacts its feminist values through its minimization of advertisements as a financial lynchpin, its insistence on one-dimensional ad appeals when they are used, and its focus on digital media output to aid that ad avoidance.

Feminism, Looking, and Advertisements

In Western culture, third wave feminism views the act of looking “more than the other senses, [as] objectifying. […] It sets at a distance, [and] maintains distance” (Irigaray quoted in Owens 70). Viewing women’s bodies as objects from a distance makes them more likely to be seen as Other. To counteract the vision of women’s bodies as things, Bitch supplants the typical advertisements one might find in Vogue or Cosmopolitan, where women’s bodies are viewed in parts and paired with idealized commodities, with one-dimensional ads that provide basic information and few images. The use of black and white and visually simple advertisements, resembling in many cases, business cards, intentionally veer away from the sexist consumerism so often found in advertisements, and instead forces the focus back to the media’s content, which is feminist.

In using its visual rhetoric to re-situate the reader’s gaze from consumerism and sexism, Bitch has been able to build its radical, feminist brand successfully and bypass a political economy “that values efficiency and profit over gender equity” (Riordan). In doing so, Bitch highlights the assertion that consumption is not power (McRobbie 75). In 2009, Bitch officially became BitchMedia and moved even farther away from visual advertising and toward a ‘sponsorship’ model, complete with its own kit. The main difference between a sponsor and an advertiser, according to BitchMedia, is that businesses who are sponsors support Bitch’s mission first rather than simply utilizing the magazine or blog as a way to market their own business or product (“Sponsorship Kit”). The move allowed businesses and organizations interested in supporting Bitch’s programs or mission to associate themselves with the non-profit’s ideals.The sponsors get visibility and marketing opportunities in Bitch magazine and on the B-Hive (Bitch’s website and blog), while Bitch gets to reorient the readership’s attention toward radical feminist content and away from the consumerism so prevalent in typical U.S. media.

Methodology

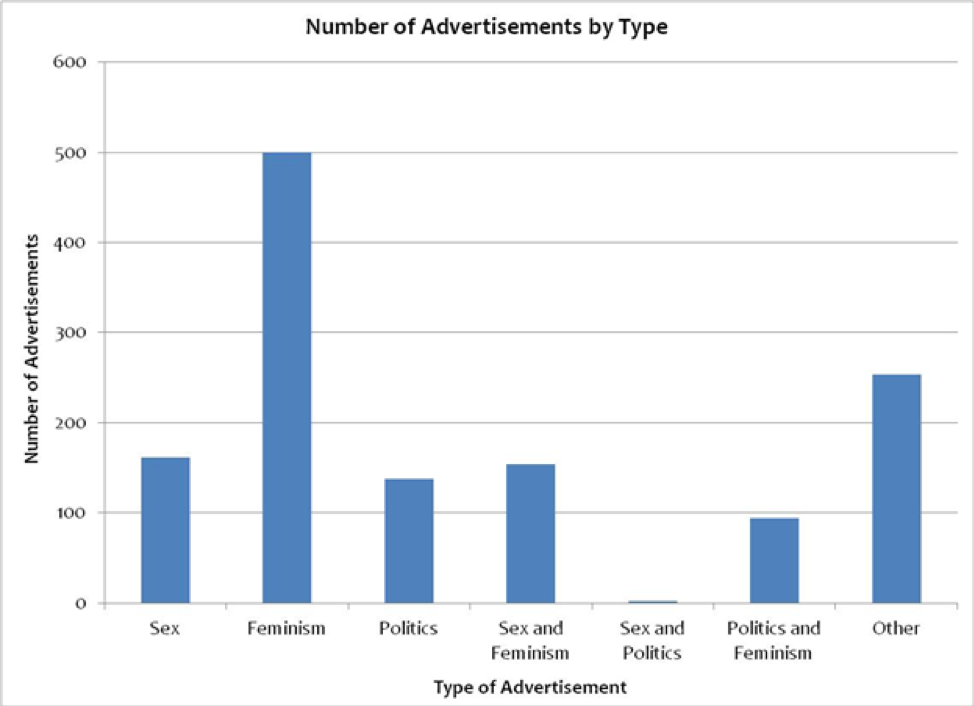

Drawing on Suzy D’Enbeau’s feminist work in media studies, and my own interest in how a media conglomerate might move away from advertising as a financial support, I quantitatively analyzed 865 advertisements from 43 Bitch magazine issues, spanning 1997 to 2013. I excluded issues: 1-5, 7-11, 15, 17, 20-22 and 25, as those issues were not available for backorder or digitally, and issues 59-84 because the advertising trend within the magazine hasn’t changed significantly in the last five years. Any advertisement specifically promoting Bitch magazine and/or Bitch Media was excluded. I observed the frequency of specific types of categories of advertisements using, as a base, the categorical rubric designed by Suzy D’Enbeau in her own published study of Bust magazine. Her three categories were:

1) sex appeals that equate sexual commodities with a tenet of feminism;

2) sex appeals that foster feminist political protest; and

3) sex appeals that promote a feminist commitment to alternative identities (58).

The categories I used were broader and more numerous than those originally identified by D’Enbeau. Based on a preliminary review of a small number of issues, it was apparent that Bitch magazine avoids publishing mainstream (traditional) advertisements using sex to sell products, even when those advertisements, like the ones in Bust magazine, queer notions of sex and sexuality. Thus, I collapsed all advertisements of a sexual nature into one category. D’Enbeau’s third category, sex appeals that promote a feminist commitment to alternative identities, is not relevant to this study since all of the sex appeals would have qualified. Instead, I used the following categories:

1) ads using sex appeal to sell products;

2) ads using a tenet of feminism to sell products;

3) ads using political protest to sell products;

4) ads using sex appeals that foster feminist political protest (that is, a conglomeration of both 1 and 3 above);

5) ads using sex appeals that equate sexual commodities [PEH16] with a tenet of feminism (that is, a conglomeration of 1 and 2); and

6) ads using something other than sex, feminism, political protest or some conglomeration of those to sell products.

Once the advertisements were coded, the frequency of each type of advertisement was tabulated overall and by issue. No inter-rater reliability for coding was done for this study. Finally, linear regression and correlation analysis were used to determine if the total number of advertisements significantly declined over time. Linear regression analysis was performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Findings

Bitch: Feminist Response to Pop Culture manages to operate within its ideals and subsist entirely on revenue from subscriptions, business sponsorships, donations, and a relatively small number of completely non-traditional advertisements. These advertisements strategically upend the traditional “sex sells” style of advertising by instead using basic advertising structures that exemplify radical feminist values, allowing the magazine content rather than the advertisements themselves to build the Bitchmedia brand.

Of the 865 ads reviewed across 43 issues of Bitch magazine, only 161 (20%) used sex appeals to sell their products. Instead, advertisements most often utilized various tenets of feminism (500 or 58%) or other forms of salesmanship (253 or 29%) to sell their products (See Figure 1). This trend persists in the most recent issues of the magazine as well. For instance, the back cover of issue 77 is an advertisement for SheBop, a “female friendly sex toy boutique: for every body.” The advertisement is visually appealing, in that it is in color, and illustrates a photo of nature. It avoids sexual innuendo entirely (See Figure 2). Rhetorically, there is no overt argument here. The only indication that this is an advertisement, and not simply a photo gracing the back cover, is the small, plain SheBop logo centered beneath the photo and its motto “for every body” playing on the fact that every type of female body, not merely highly sexualized or photo-shopped ones, are welcome. This ad represents the Other category since, though it’s in color, it shows no people, in no way relates to its product, and does not indicate a feminist ideology, except in its tacit acceptance of women using sex toys.

The next most popular type of advertisement in Bitch are those with a political protest slant (154 or 18%). Many of these ads, for companies like GladRags, Lunapads, or the Gaia Collective focus on sustainability and environmentalism to sell their products to the readers of Bitch media, knowing that the Bitchmedia audience leans left and cares about such issues. These ads appear repeatedly in subsequent issues of Bitch magazine with little to no change. Some, like GladRags, have a rotation of ads they use, whereas the Gaia Collective’s ad generally stays the same across issues. In issue 64, the Love/Lust issue, the Gaia Collective uses its standard advertisement (see Figure 3).

From a financial point of view, monochromatic advertisements that are reused save the advertised companies money. Likewise, Bitch rarely changes the layout of these ads on the page and generally maintains the same space for advertisements across issues: inside the front and back cover, on the back cover, and a two-page spread in the center of the magazine. This consistency saves Bitchmedia the hassle, time, and expense of having to reorganize proof pages prior to printing. Not changing ads or the layout of the ad pages and their placement in the magazine also underscores that the content of the articles is what’s most important here–not the advertisements, the products they sell, or the companies that sell them.

Given the audience for Bitch, it is unsurprising that 94 (11%) ads used a combination of political protest and feminism. A common advertiser in Bitchmedia is Ms. Magazine. One of its ads, in issue no. 77, pushes for readers to get the tablet edition of Ms. and illustrates the feminist, political protest category (See Figure 4).

The crowd is meant to be an image of the Women’s March, as indicated by the small words “Spring 2017 Women’s March Issue” that appear in the upper left-hand corner of the tablet image. The ad itself is visually simple; the three easy steps neatly printed below the tagline explain just how easy it is to go paperless. Like the colorful Shebop ad on the back cover of the same issue (Figure 2), this ad makes little attempt to push its product on the Bitchmedia audience. It presents a fellow feminist publication, one likely to be well-known by Bitchmedia’s audience, shows them how to get the online version in three easy steps, and simultaneously acknowledges the Women’s March. Ms. varies the focus of the ads it prints in Bitch but not the image/layout used across several issues. The topics range from fast-food workers’ rallies for improved wages to activist movements like the Women’s March, but all of them clearly understand their audience’s values: feminist, activist, and digitally-savvy. The ads do not attempt to distract from the magazine’s content with further visual appeals, an interesting rhetorical choice for the advertisers to accept, given the traditional use of visuals to attract readers’ attention. It’s clear that the advertisers are in agreement with the editors of Bitchmedia that what is being said matters more than what is being sold. In fact, of the 161 sex appeals found in Bitch magazine, only nineteen did not share a feminist tenet or political protest message, and all of those ads were from the same sex toy company, Shebop.

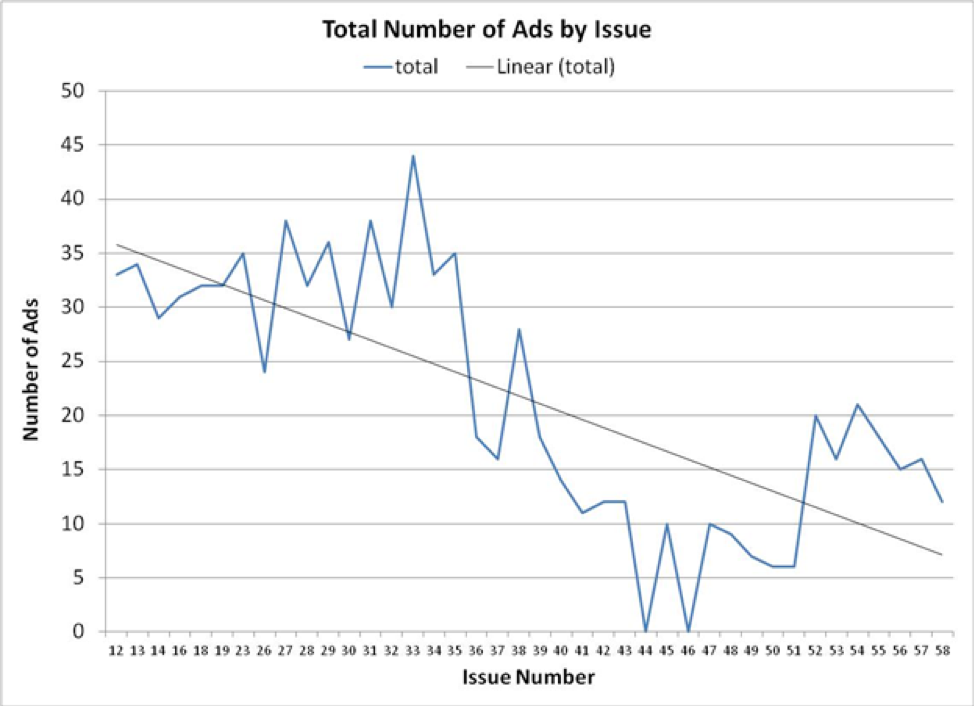

The total number of ads by issue is shown in Figure 5. Linear regression revealed a significant downward trend in the number of ads in Bitch (p-value < 0.0001). As Bitch has become more popular, more colorful, and more expensive, it has also managed to utilize fewer ads in its magazine, thus adding to its particular brand iconography: idealistic, feminist, radical, and savvy. In fact, 2 issues, numbers 44 and 46 had no ads at all. There is a caveat to this: three issues of Bitch: issues 52, 53, and 54 had more than double the number of ads than the average number in the previous ten issues. Although the total number of ads increased, none were noted to be contrary to Bitch’s feminist ideology. Likewise, the downward trend returned with the subsequent issues and is continuing.

Bitch Branding and Financial Struggles

The industry of news/media is vulnerable to manipulation; that capitalist culture is a society built out of brands where consumerism is how we “express our sense of social belonging” (Sinclair 216) means that companies vying for consumer ‘affections’ must work hard to maintain their brand’s reputation via carefully crafted visual, rhetorical appeals. As an independent, feminist magazine, Bitch has had to work harder than many mainstream brands to continually appeal to its audience since traditional sex-sells advertisements were not a financial option.

Bitch maintains its unique brand of feminism by avoiding reliance on large companies’ sex-sells advertising revenue to survive. Doing so has historically meant that they are financially vulnerable and must resort to creative, rhetorical tactics for staying afloat. While Bitch has a self-advertisement of some sort in every issue as well as thank-yous to donors, plugs for the B-hive and Bitchfest, and requests for funds, during 2006 they took a more direct fundraising tactic.

The editors of Bitch magazine included in four straight issues in 2006 (issues 31, 32, 33 and 34) a page-long section detailing Bitch’s history, values, and need for “financial contributions over and above the cost of the magazine itself” (issue 31, 23). This rhetorical move overtly claims that “mainstream magazines devote 65% of their space to ads, [but] ads in Bitch take up [only] about 12%” (issue 32, 22), aligning their financial choices with the values of their feminist audience. Bitch claimed that being so transparent about their finances, financial struggles, and commitment to non-traditional funding sources enabled them to “talk back to the forces-like the cosmetic industry […] without fear of losing their advertising dollars” (22). The end of the one-page ads coincides exactly with Bitch’s move from Oakland, CA (issue 34) to Portland, OR (issue no. 35). It seems possible that overhead may have lessened with the move. However, the funding requests didn’t cease entirely, forcing Bitch to utilize a different visual media to get help from their audience than their typically one-dimensional print advertisements.

In September 2008, Bitch posted a YouTube video asking for $40,000, the cost of one issue’s publication. The editor, Andi Zeisler, cited the dwindling popularity of print media as the source of this shortfall. Doing so via a popular online media was a rhetorically savvy move as it reinforced the exact claim she was making about Bitch’s audience shifting its interests toward media other than print magazines. The fact that the video was watched by thousands of people and produced the donations Bitch needed to stay afloat furthers Zeisler’s point that Bitch’s audience was shifting and Bitch needed to keep pace. Bitchmedia’s current form exemplifies that the founders were listening to their readership as feminists but also, ironically, as consumers. The video also incited, along with several supportive posts, the influx of donations and the eventual move to Bitchmedia, a scathing critique on Jezebel.com.

The September 2008 article by Tracy Egan Morrissey titled “The Struggles of Bitch Magazine Are Neither Surprising Nor New” was unabashed in its condemnation of “why such stringent idealism isn’t exactly realistic” (Jezebel.com), but Morrissey was mistaken. While it’s important to consider whether a magazine’s contribution to the public discourse is significant enough to warrant its survival, the fact is that, since this moment in Bitch’s history, it has thrived and expanded. Its success suggests that its content is desirable, and its ability to rhetorically appeal to its audience, even as it evolves, is on point. Through its now multimedia organization, BitchMedia, the conglomerate has successfully launched the B-Hive, an online subscription-based sustainer membership program; created a free blog site; begun selling merchandise with the Bitch name emblazoned on it; published the book Bitchfest; sponsored two ongoing podcasts; and continues to put out its feminist response to pop culture, all while maintaining ‘stringent idealism’.

A major tenet of feminism is the belief that women should have equality in society and actively work towards that goal. With such a small, affluent, and diverse group of readers, a tiny circulation, and an obvious absence on myriad bookstore and grocery store shelves, Bitch Magazine would likely be less effective in its goal of responding to popular culture using a radical feminist lens. However, with the advent of Bitchmedia, Bitch’s potential to reach larger and more diverse audiences continues to grow. Its endurance via the use of visually bland, one-dimensional, and highly-repetitive advertisements, as well as its extension into new media, allows it to appeal to its feminist audience while staying afloat financially. This clever financial structure, coupled with its savvy use of visual rhetoric and new media technologies, offers other ideological, fringe news sources an effective schema for branding and expansion.

Works Cited

- D’Enbeau, Suzy. “Sex, Feminism, and Advertising: The Politics of Advertising Feminism in a Competitive Marketplace.” Journal of Communication Inquiry, vol. 35, no. 1, 2011, pp. 53-69.

- Jervis, Lisa and Andi Zeisler, eds. Bitch: Feminist Response to Pop Culture, 1996-2011, pp. 1-53.

- McRobbie, Angela. “Bridging the Gap: Feminism, Fashion, and Consumption.” Feminist Review, vol. 55, 1997, pp. 73-89.

- Morrissey, Tracie Egan. “The Struggles of Bitch Magazine Are Neither Surprising Nor New.” Retrieved from Jezebel.com. September 16, 2008. <http://jezebel.com/5050695/the-struggles-of-bitch-magazine-are-neither-surprising-nor-new>

- Owens, Craig. “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism.” The Anti-Aesthetic Essays on Postmodern Culture. Edited by Hal Forester. Bay Press, 1983. pp. 57-82.

- Riordan, Ellen. “Intersections and New Directions: On Feminism and Political Economy.” Sex and Money: Feminism and Political Economy in the Media. Edited by Eileen Meehan and Ellen Riordan. U of Minnesota P, 2002, pp. 3-15.

- Sinclair, John. “Branding and Culture. Chapter 10.” The Handbook of Political Economy of Communication. Edited by Janet Wasko, Graham Murdock and Helena Sousa. Blackwell, 2011, pp. 206-222.

- Steinem, Gloria. “Sex, Lies and Advertising.” Ms. Magazine, vol. 12 no. 2, 1990, pp. 60-64.

Keywords: media studies; rhetorical analysis; feminism; visual rhetorics; branding

Cover Image Credit: Fair Use of Bitch magazine cover

Sarah Austin is a PhD candidate at Texas Tech where she serves as the RSA student chapter Vice President, and studies intersectional feminist rhetorics. Sarah is a Lead English Instructor at USAFA Prep, co-editor of Academic Labor: Research & Artistry, and book review editor for the Journal of Veterans Studies.

Sarah Austin is a PhD candidate at Texas Tech where she serves as the RSA student chapter Vice President, and studies intersectional feminist rhetorics. Sarah is a Lead English Instructor at USAFA Prep, co-editor of Academic Labor: Research & Artistry, and book review editor for the Journal of Veterans Studies.