Pressurized Rhetorical Bodies: Student-Athletes between Feeling Rules and Affective Publics

It’s March 2019, and I’m trying to imagine how my university’s men’s basketball team is handling a tough loss in the NCAA tournament. As the team’s Twitter account offers, “It’s not how we wanted the season to end, but thank you to #BearcatsNation for your support all season long” (GoBearcatsMBB). I’m trying to imagine if players are watching the replies from fans and naysayers on social media. Collegiate athletes put their careers at stake when they compose and respond to messages in the public streams of social media. In recent years, athletes have been punished by––and sometimes removed from––their respective teams based on social media commentary (Hauer; Penrose; Goodwin; Gore). In response to such incidents, many universities have created social media policies for student-athletes. In a recent semester, for example, two student-athletes in my section of first-year composition spoke of an orientation that new student-athletes attend when they arrive to campus. The athletes receive a handbook with rules and policies that encourages athletes who use social media, such Twitter and Facebook, to refrain from posting negative comments about rival teams, teammates, and life events. They are told to accord with directives such as:

Never criticize an opposing team, referee, coach, or teammate.

Engage and be active on social media. Don’t go weeks without a post.

Don’t use social media as an outlet to complain about your life, teammates, school, etc. (University of Cincinnati Athletics)

If you’re a student-athlete reading those rules right now, in a present moment rife with burning cities and anti-racist protests, what might you write on social media?

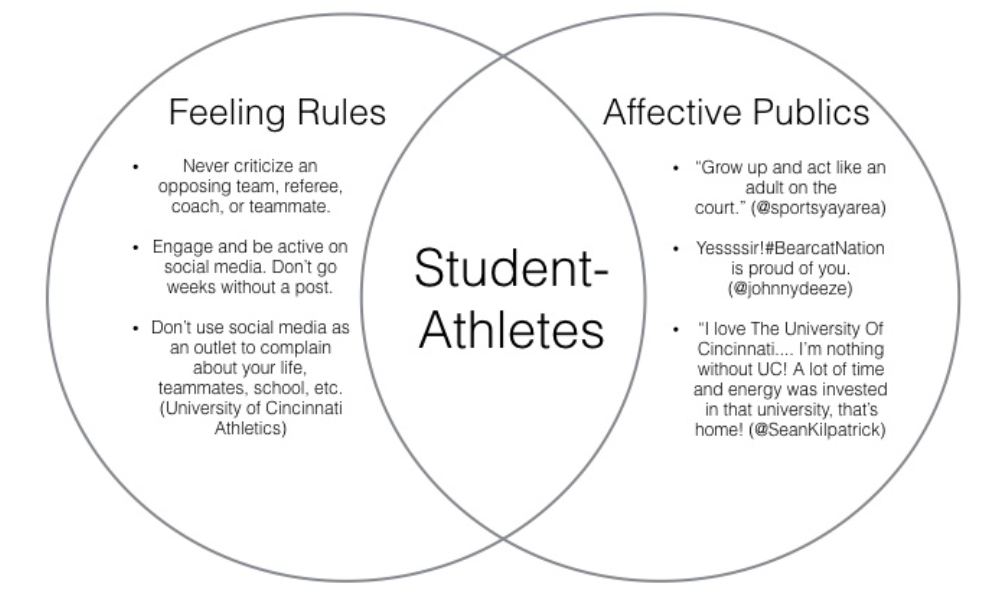

In this essay, I develop and apply a theoretical framework for analyzing student-athletes’ rhetorical activity. This university handbook is a focal point of my analysis, for it chills student-athletes’ negative talk and enacts what Arlie Hochschild and Adia Wingfield define as feeling rules. As Hochschild writes in The Managed Heart, feeling rules attempt to regulate how workers behave in social environments, behaviors that include speaking and writing to peers and publics. Feeling rules are useful for my discussion because they speak to a larger body of scholarship that accounts for ways in which material and immaterial forces––including emotioned texts and communal feelings––impinge on bodies (Ahmed, Gregg, Micciche, Papacharissi). As Melissa Gregg shows, workplaces that privilege positive affect(s)––“serve with a smile”––run counter to the emotions of workers. We might see a breakdown of “professional cool” demanded by the workplace. For Gregg, the website Passive-Aggressive Notes allows affects to proliferate without “local criticism or other embarrassing displays of affect that face-to-face confrontation might threaten” (258). Indeed, “PELASE [sic] DON’T LET ME CATCH YOU STARVING MY CHILD (UNBORN OR NOT) BY TASTING, EATING, OR STEALING MY FOOD” (258) circumvents the professional cool of the office by invoking anger and shame. Professional cool is a managed emotion and the Post-Its serve as an ethos-protecting mechanism.

Similar to training in which office workers learn to muster a smile, student-athletes who accord with university-sponsored feeling rules embrace their positive feelings and leave out the negative. At University of Cincinnati, “social media is the front lawn” (University of Cincinnati Athletics), and the university’s implied message is that positive expressions in public keep student-athletes in good standing with coaches and prospective professional teams. Ethos, then, is contingent on professional cool, on emotionally selective writing and actions on and off the playing field.

I problematize feeling rules and their impingements on students-athletes by calling attention to social media posts by student-athletes and publics. Students-athletes post amid what Zizi Papacharissi calls “affective publics,” a term which describes publics that post and circulate messages that cultivate ambient streams of emotion. The streams circulate and intensify in digital environments. Affective ambient streams apply pressure to feeling rules (e.g., the handbook) that regulate bodies and texts of student-athletes, and conversely, the rules attempt to suppress ambient streams that might instigate student-athletes. Put differently, students-athletes are pressurized rhetorical bodies, caught in the middle of feeling rules and affective ambient streams. While rule-abiding student-athletes are expected to refrain from getting into “heated arguments” (University of Cincinnati Athletics) on social media, those arguments—part of Papacharissi calls ambient streams—keep moving indefinitely and pressing on such rhetorical bodies. For student-athletes, then, the stakes of social media activity are high as they embody professional cool and affective publics.

Figure 1 functions as a guide to my discussion in this essay. Twitter and various social media are rhetorical tools for journalists, activists, presidential nominees and athletes. Understanding how feeling rules and affective publics impact the rhetorical work of student-athletes can help us better understand public rhetorical activity in our present moment. Meg Penrose posits that student-athletes’ messages––say, a Facebook post or a Tweet–– are likely to be circulated by media and fans eager to highlight a public controversy (48). Student-athletes are more vulnerable, that is, to the pressures of affective publics, at a time when their performance and professional cool might lead to a professional career. I work my way back to the above figure and discussion by offering a brief history of social media rules and rulings for student-athletes and then discussing potential pressures from affective publics. Indeed, if ambient streams apply pressure to feeling rules, then students-athletes are pressurized rhetorical bodies. Eventually, something or someone cracks under pressure. We simply cannot ignore affective and institutional forces that limit and drive (physical and digital) bodies of rhetorical action.

Rules and Affects

Social media policies are nothing new among schools and scholarly inquiries in the realms of communication (Sanderson and Browning; Vie, Weber), higher education (Pomerantz et al.; McNeill) and legal studies (Hauer; Penrose). From a legal studies perspective, Penrose reminds readers that student-athletes’ public commentary has long been under scrutiny by coaches and universities. The University of Michigan’s athletics department, for example, prohibits “offensive language, personal attacks or racial comments” and any “information about your team, the athletic department or the University that is not considered public knowledge” (University of Michigan). Elsewhere, the University of Cincinnati student-athlete handbook also implores its readers to withhold “slang/bad language. Don’t reference parties, gambling, drugs, alcohol, etc.” (University of Cincinnati Athletics). While student-athletes have abided by such policies and edicts for decades (see Snyder et al.), social media is a rather new way in which student-athletes embody ongoing affective forces that stem from feeling rules and affective publics. “Student-athletes,” Penrose argues, “wear two separate hats––one as a student, where robust First Amendment rights remain, and another as an athlete, where speech and expression rights have long been regulated by coaches, athletic departments and even athletic conferences” (35). That duality and the affective forces that emerge from rules and publics are in conflict when fans and detractors beckon student-athletes to join social media discourse. In the social media landscape, fans want 24/7 access to athletes, but athletes may not be permitted to respond in kind lest they’re lambasted by coaches or dismissed from the team (see Sanderson and Browning).

Embodying UC’s handbook, former shooting guard Sean Kilpatrick could say something like, “I love The University Of Cincinnati…. I love the city of Cincinnati that’s home for me, that’s where that city turned me into a MAN. I’m nothing without UC! A lot of time and energy was invested in that university, that’s home! #UC” (@SeanKilpatrick). But, if he were upholding his school’s feeling rules, he couldn’t say something like the following: “That tournament game was a brutal one, and so were the fans. I’m glad it’s over.” Rules, in other words, put pressure on student-athletes like Kilpatrick to stay cool and positive. Perhaps earlier in his career Kilpatrick was trained by the athletics department to avoid expressing discontent in public. Perhaps he also understood ways in which foul language and negative talk could feedback into his character, his good standing as a student-athlete on the brink of graduation.

I want to amplify the significance of feeling rules by turning to Marcus Hauer’s claim that a primary conflict between student-athletes and universities is money, or the cashflow that athletic programs build through success, fandom, and more. Despite student-athletes’ training, limitations and outright bans of social media use, “it would only take a single individual (not denied access by privacy settings) to take a screenshot of the social media speech and then place it on a website to make it available to the world” (Hauer 429). Hauer suggests that student-athletes who are dismissed for negative and even racist commentary (see Gore) have a direct impact on a program’s revenue and ethos. In Sara Ahmed’s terms, the “affective economy” of an athletic program is a stake when student-athletes use social media.

Toward Affective Publics and Professional Cool

Legal studies emphasize the stakes for student-athletes and open a discussion that emotion––and its symbiotic sibling, affect––circulates and intensifies in physical and digital spaces. In addition, they demonstrate that fans and publics do not play by the same rules on social media. Fan sentiments as ambient streams––perhaps 24/7, especially for nationally renowned programs––put pressure on student-athletes who abide by feeling rules. Thus, student-athletes are pressurized by competing rhetorics and affects. Under the domain of affect theory, affect is bodily, pre-linguistic, a “background feeling” (Damasio qtd. in Rickert 147). For Teresa Brennan, affect, like an atmosphere, transmits in rooms, objects and bodies: “[By] the transmission of affect, I mean simply that the emotions or affects of one person, and the enhancing or depressing energies these affects entail, can enter into another. A definition of affect as such is more complicated” (3). Emotion is also a social phenomenon, attached to bodies, texts and genres; texts and genres stick to and spread across porous spaces (see Ahmed; Micciche).

Theories of affect and emotion––however social, effable or ineffable––become more tangible with specific case studies. Theorizing “affective publics,” Papacharissi’s work examines the circulation of sentiments on Twitter in response to political unrest and interventions, from the Arab Spring to the Occupy movement. As an online genre in which composers write tweets in 280 characters or less, Twitter has served as a platform for circulating affect and sticking emotions to textual and visual production. Through Twitter, citizens can transmit sentiments on a global scale, and emotions continue to intensify when they see response and uptake from publics, whether news reporters or concerned parties. Intensification leads to what Papacharissi calls ambient streams––those always-on opinions moving across social media like Twitter: “[T]his ambience is essential in providing constant updates, even when not much is happening or other media are not covering the story” (130). Her comment suggests that such an ambience doesn’t go away if I turn off my screen; affective publics continue moving, evolving, subsiding, intensifying…. Papacharissi’s theory is useful here because it addresses sensations and social expressions that drive public compositions across spaces. Twitter users have created change by reporting discontent for political powers. In sports circles, they have praised and heckled student-athletes, even UC’s men’s basketball team coach (see @sportsyayarea; and @SeanKilpatrick and @johnnydeeze). Affective publics show the transitory nature of emotion again, socially performed and transmitted across spaces, even without the initial rhetor’s consent or desire.

Future Pressures

It’s September 2019 and freshman guard Jeremiah Davenport is featured in a tweet by UC’s men’s basketball team: “Growing up, Cincinnati was a big-time school for me… I always loved UC. I always dreamed of coming here. Now I have the opportunity. Now I’m here.” The aforementioned discussions of feeling rules and affective publics cultivates a theoretical framework that implicates student-athletes’ responses. Throughout their academic journey, student-athletes are subjected to rhetorical-affective pressures, tasked with negotiating their university’s feeling rules and the seemingly lawless and limitless world of (sports-related) affective publics that manifest through Twitter and the like. It does not seem easy for them to embody both, to take on those pressures while focusing on said game at hand. Feeling rules and affective publics aren’t constrained to certain spaces, that is. Rather, these amorphous entities of pressure come alive in and pulse through arenas, physical bodies, and online environments. Perhaps it’s needless to say that Davenport has some serious work ahead of him––on and off the court.

Pitting feeling rules against affective publics, and examining how student-athletes are placed at their center, raises future research questions about pressurized rhetorical bodies and social justice movements. How have student-athletes and professional-level athletes accorded with institutional feeling rules and engaged with the rhetorical-affective work of activists and oppositions? In 2015, local publics were circulating messages––doing emotion––in support and opposition of the #Irate8, a student-driven hashtag and social group that called for justice and change after an unarmed African-American man was shot and killed by a university police officer (see Micciche’s “Staying with Emotion” for a rhetorical perspective). In May 2016, local publics distributed and circulated messages with the hashtag #JusticeforHarambe after officials at the Cincinnati Zoo killed a 400-pound gorilla thought to be endangering a young child. Both controversies happened during the regular seasons of the Cincinnati Reds and Bengals. And soon after, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick was kneeling during the US National Anthem to protest systemic racism. As Michael Rosenberg asks in Sports Illustrated, “He lost his career over it. And this brings up the question: What would America make of Colin Kaepernick now?” Put differently, if today’s professional and collegiate athletes affiliate with social justice movements, what pressures and consequences will they face?

Besides studying similar populations who face institutional rules and ambient streams, we also need to explore spaces in which students-athletes and others seek refuge from public scrutiny––to release the pressures they embody. One notable space is the “Finsta” account, or a fake and anonymous Instagram account designed to circumvent scrutiny from coaches and the like. However, Leada Gore and Shaun Goodwin have reported on the consequences of student-athletes who post in seemingly discrete spaces. Besides private and anonymous social media, we might consider campus support programs––from peer groups to counseling––that help students feel their way through opinions and emotions that are not permitted in their public rhetorical spaces. Perhaps my former university’s men’s basketball team has found solace in closed doors, where the pressures of losing a roster spot and fanning the flames of public criticism are neutralized.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Routledge, 2004.

Brennan, Teresa. Transmission of Affect. Cornell UP, 2004.

@GoBearcatsMBB. “Growing up, Cincinnati was a big-time school for me… I always loved UC. I always dreamed of coming here. Now I have the opportunity. Now I’m here.” – Freshman guard Jeremiah Davenport #Bearcats | @J24Davenport.” Twitter, 10 Sept. 2019, twitter.com/J24Davenport/status/1171824558455869441.

Goodwin, Shaun. “Seven Kansas Rowers Suspended amid Social Media Scandal.” University Daily Kansan, 22 Apr. 2018, www.kansan.com/sports/seven-kansas-rowers-suspended-amid-social-media-scandal/article_6be7c8c4-4676-11e8-8a56-13d66c809639.html.

Gore, Leada. “College Athlete Apologizes for Racist Social Media Post: ‘It was Horrendous and Disgusting.’” AL.com, 31 Jan. 2018, www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2018/01/college_athlete_apologizes_for.html.

Gregg, Melissa. “On Friday Night Drinks.” The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Duke UP, 2010.

Hauer, Marcus. “The Constitutionality of Public University Bans of Student-athlete Speech through Social Media.” Vermont Law Review, vol. 37, 2012, pp. 413-436.

Hochschild, Arlie R. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. U of California P, 1983.

@johnnydeeze. “@SeanKilpatrick Yessssir! #BearcatNation is proud of you. One of the best to come through #UC.” Twitter, 17 May 2018, twitter.com/johnnydeeze/status/997311385989238784. Accessed 31 May 2018.

McNeill, Tony. ‘‘‘Don’t Affect The Share Price’: Social Media Policy in Higher Education as Reputation Management.” Research in Learning Technology, vol. 20, 2012, doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.19194.

Micciche, Laura. “Staying with Emotion.” Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, compositionforum.com/issue/34/micciche-retrospective.php.

Papacharissi, Zizi. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. Oxford UP, 2014.

Penrose, Meg. “Tinkering with Success: College Athletes, Social Media and the First Amendment.” Pace Law Review, vol. 35, 2014, pp. 30-72.

Pomerantz, Jeffrey, Carolyn Hank, and Cassidy R. Sugimoto. “The State of Social Media Policies in Higher Education.” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 5, May 2015, doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127485.

Rosenberg, Michael. “What Do You Think of Colin Kaepernick Now?” Sports Illustrated, 1 June 2020, www.si.com/nfl/2020/06/01/colin-kaepernick-and-george-floyd-protests.

Sanderson, Jimmy, and Blair Browning. “Training Versus Monitoring: A Qualitative Examination Of Athletic Department Practices Regarding Student-Athletes And Twitter.” Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, vol. 14, no. 1, 2013, pp. 105-111.

@SeanKilpatrick. “I love The University Of Cincinnati…. I love the city of Cincinnati that’s home for me, that’s where that city turned me into a MAN. I’m nothing without UC! A lot of time and energy was invested in that university, that’s home! #UC.” Twitter, 16 May 2018, twitter.com/SeanKilpatrick/status/996852899115339776. Accessed 31 May 2018.

Snyder, Eric M., et al. “Social Media Policies in Intercollegiate Athletics: The Speech And Privacy Rights Of Student-Athletes.” Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, vol. 9, no. 1, 2015, pp. 50-74.

@sportsyayarea. “Replying to @CoachCroninUC. They’re both more mature than you. Grow up and act like an adult on the court.” Twitter, 29 Apr. 2018, twitter.com/sportsyayarea/status/990636375107035136

University of Cincinnati Athletics. 2019-2020 University of Cincinnati Student-Athlete Handbook. University of Cincinnati, 27 Aug. 2019, p. 60, issuu.com/universityofcincinnatiathletics/docs/2019-20_sa_handbook. Accessed 10 Sept. 2019.

University of Michigan. “Social Media Guidelines.” 2018, mgoblue.com/sports/2017/6/16/compliance-sa-social-media-html.aspx?id=342. Accessed 31 May 2018.

Vie, Stephanie. “Training Online Technical Communication Educators to Teach with Social Media: Best Practices and Professional Recommendations.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 3, 2017, pp. 344-359.

Weber, Ryan. “Constrained Agency in Corporate Social Media Policy.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 43, no. 3, July 2013, pp. 289–315, doi:10.2190/TW.43.3.d.

Wingfield, Adia Harvey. “Are Some Emotions Marked ‘Whites Only’? Racialized Feeling Rules in Professional Workplaces.” Social Problems, vol. 57, no. 2, 2010, 251-268.

KEYWORDS: emotion, social media, sports, public rhetoric

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: https://unsplash.com/photos/vPFu9_rIJFc

Rich Shivener is an assistant professor in the Writing Department at York University. His latest research investigates digital media writing practices and emotions, and he teaches courses in the department's Digital Cultures stream. Rich is also an associate editor for the digital journal Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy.

Rich Shivener is an assistant professor in the Writing Department at York University. His latest research investigates digital media writing practices and emotions, and he teaches courses in the department's Digital Cultures stream. Rich is also an associate editor for the digital journal Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy.