“People Were Being Nasty”: White Fragility and Calls for Collective Violence against Scholars of Color

Scholars from marginalized communities have consistently lamented the erasure of our work and of the unrecognized and uncompensated labor exacted upon our bodies to articulate the corpus of this work on demand (Calvente, Calafell, and Chávez; Mejia; Sowards; Valdivia). This double-bind of being the invisible academic whose work is not read by your peers—though it appears in the same venues—but whose knowledge is expected to be available on demand, like a genie conjured for their master, is racist. This unrecognized and uncompensated labor is part of the reason our ratio of tenured and full professors is lower than that of white academics, as our considerable accomplishments are evaluated as less noteworthy than the equivalent (or even lesser) accomplishments of our peers (Gutiérrez y Muhs, Flores Niemann, González, and Harris; Mejia; Moffitt and Harris). Moreover, our time as first-generation, Latinxs is spent providing services to our peers on skills they themselves should possess (e.g., how to use a search engine or read through a reference list to learn more about any aspect of marginalization). None of this is new information, nor should it be surprising, but to some it will be, as to them we are invisible after all—until we are not.

Marginalized scholars are expected to speak on demand and be grateful for having been demanded. Dominant scholars mistake our strategic acquiescence as consent, presuming that because one of us has answered the call—or even perhaps because we had once answered the call—that we as a collective should always answer the call. This is to mistake our war of position for a war of manoeuver. As Stuart Hall, interpreting Gramsci, argued, there needs to be a distinction between those struggles “where everything is condensed into one front and one moment of struggle” (the war of manoeuver) and that “which has to be conducted in a protracted way, across many different and varying fronts of struggle” (“Gramsci” 17). As Hall continues, “what really counts in a war of position is not the enemy’s ‘forward trenches’ but […] the whole structure of society” (“Gramsci” 17). Hall believed the only “game in town worth playing is the game of cultural ‘wars of position’” (“What” 258), as “there is rarely a single break-through which wins the [socio-political-economic] war once and for all” (“Gramsci” 17). Sometimes we consent because we hope that our answers will work towards the transformation of the whole structure of society—where our work is read and engaged like others—and sometimes we refuse because we believe that our answers will only work to keep the system of summoning intact. Neither should be mistaken for a war of maneuver: we answer with the hope of transforming the system, we refuse with the hope that we might survive the system.

This essay is concerned with what we have described above as the politics of summoning. We offer our own experiences as a case study in order to demonstrate how white scholars evoke these summonings, the means by which they reprimand and attempt to retain control of those who refuse to answer their call, and their calls for collective violence against scholars of color when we refuse to comply.

Setting the Stage: White Fragility

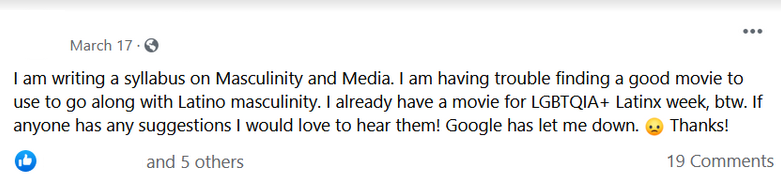

On March 17, 2021, we were summoned. The ritual took place on the Facebook page for a large group of scholars from the field of communication studies. The group “Communication Scholars for Transformation” (CST) was created on June 13, 2019 in response to a convergence of events in the field of communication (e.g., #CommSoWhite). The CST FB page was envisioned as a space for developing and implementing “diversity and inclusion strategies in the communication field writ large” and providing “support for colleagues on the margins.” Two years later (July 26, 2021), the group consists of 4,033 members. With a membership of this size, it was only a matter of time that we would be summoned:

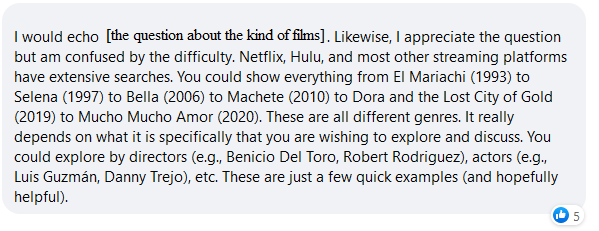

Immediately people began answering the call: “Maybe look at Y Tu Mamá También or Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights”; “https:en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_Moons”; “The Remake of West Side Story?” Most responded in this format, likely as the summoner had hoped—offering straightforward responses and not deconstructing the implications of the original poster’s request. One respondent did request more information—“Are you looking for examples that are disruptive? Films that challenge norms? Films that reinforce stereotypes”—but their question was ignored.

This lack of public gratitude by the original poster [hereafter OP] is consistent with the historical practice of white people and institutions feeling entitled to, not recognizing, nor compensating the work done by people of color (Gutiérrez y Muhs, Flores Niemann, González, and Harris; Martínez; Moffitt and Harris). The historical record shows that people of color are more likely to be reprimanded (often violently) for real or imagined violations of white entitlement than we are to be recognized, praised, let alone compensated for acting as desired (Ore; Martínez). This is especially so when the case involves perceived transgressions against white women (as is the case with the OP), for white women have long been “metonymically constructed […] as the physical embodiment of the nation” (Ore 20). This metonymic positioning means that though “the subordination of white women took the form of protection of the ‘weaker sex,’ [with] white women’s agency […] severely constrained,” white women “were permitted to have a derivative relationship to power denied to Black women” (Harris 322). This derivative power, Cheryl Harris argues, produces the “structural and ideological incentives for white women’s alliance with white male power” (322). White women are taught that the “restoration” of their “honor” is a virtuous act: “the circuit between white women’s tears and white men’s rage means that because [white women] cry, marginalized people can die” (Phipps 90; see also Ore). Consistent with this historical record, outside of five Facebook likes, only one of the 18 responses was deemed “transgressive” enough to receive any public comment from the OP: our own.

Minutes after the commenter above asked about the kind of films being requested, one of us responded to the original post with: “‘I am having trouble finding a good movie to use to go along with Latino masculinity.’ How?  F.” The comment was meant as a sign of sympathetic frustration regarding the state of Latino representation in the media—as in the popular 2014 meme of “press F to pay respects” from the Call of Duty franchise.1 As people continued to respond with recommendations (with some liking our comment), one of us added a few hours later:

F.” The comment was meant as a sign of sympathetic frustration regarding the state of Latino representation in the media—as in the popular 2014 meme of “press F to pay respects” from the Call of Duty franchise.1 As people continued to respond with recommendations (with some liking our comment), one of us added a few hours later:

15 minutes later, another one of the authors would reply to our “How?” comment with “right?” Though they had received 14 fairly straightforward recommendations, our comments were deemed by them to be transgressive, as two hours later the OP responded to our “How?” and “Right” comments with “[author’s name] Fuck you both,” then subsequently shut off all commenting for the post.

The reaction of the OP to our presumed frustration—which the OP inferred correctly for one of us but incorrectly for the other—regarding the flippancy of their request and erasure of our work and culture is illustrative of white fragility.2 The concept of white fragility states:

White people in North America live in a social environment that protects and insulates them from race-based stress. This insulated environment of racial protection builds white expectations for racial comfort while at the same time lowering the ability to tolerate racial stress […]. White Fragility is a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation.

(DiAngelo 54)

Everything about the OP’s request and subsequent response resonates with this description of white fragility: (1) the OP’s reliance on Google—instead of a specialized academic search engine or engagement with prior scholarship on Latinx media studies (which is a robust field)—suggests that they have limited to no expertise, knowledge, or experience on the topic of which they are interested in teaching. Whereas most would recognize the limits of their qualifications, the OP’s insulated intellectual environment builds their expectations for racial pedagogical comfort. (2) The moment the OP is challenged, they respond with anger and by leaving the “stress-inducing situation” (in this case turning off the comments). Whereas most would conclude their analysis of white fragility here—as a psychological symptom of whiteness—we need to recall that white fragility functions to “reinstate white racial equilibrium” (DiAngelo 54), not just on the interpersonal level, but the socio-political-economic as well (Applebaum).

With Friends Like You, Who Needs Enemies?

Had the incident with the OP ended with the original post, then it would be an example of an isolated microaggression. As Sue et al. define them, microaggressions are those “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities […] that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (“Racial Microaggressions” 271). Though these slights may be brief, as Sue et al. argue, the term microaggression is meant “to refer to ‘everyday’ rather than being lesser or insignificant” (“Disarming Racial” 131). Even when seemingly insignificant, however, microaggressions add up. As Chester Pierce notes, “at the end of the day I may have, in fact, done all the same things that a white man did. Yet I had to use up much more energy ‘being black.’ [….] I dissipated myself where the white did not, judging and gaging if I should speak to a person and if so how enthusiastic a greeting I should express (for the […] white [person] may prefer not to recognize me)” (301-302). Microaggressions, hence, matter on their own terms; and, as Sue et al. note, microaggressions and macroaggressions (i.e., institutional and structural oppression) are intimately related, feeding into and sustaining each other (“Disarming Racial”). Our experiences are illustrative of this phenomenon.

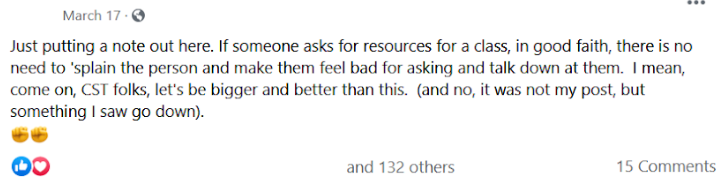

As previously mentioned, the Communication Scholars for Transformation group consists of 4,033 members with a proclaimed commitment to developing and implementing “diversity and inclusion strategies in the communication field writ large” and providing “support for colleagues on the margins.”3 Considering the public display of white fragility, it is not unreasonable to expect some level of support for us to manifest from a sizable group of proclaimed advocates. But support came from only 5 much appreciated members (in the form of likes), or approximately 0.13% of the group.4

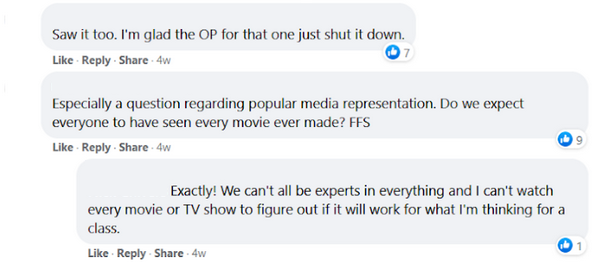

To be clear, we understand there are numerous reasons people may not have responded (e.g., social anxiety, not having seen the post). What is striking is not that only 5 colleagues responded with support for us, but rather that 134 people responded in support of the OP, or 3.4% of the group—27 times as much support as we received.5 And whereas we received 5 likes, this individual received 12 public comments in support (not counting the OP’s responses). The support began less than an hour after the OP told us “fuck you both” and shut off comments, when a senior scholar of color in the field posted:

From here, the backlash against us quickly followed:

The OP soon chimed in as well, responding to the senior scholar who initiated the backlash post: “Thank you. I turned off the comments because people were being nasty. A [L]atinx scholar saw the post and shared some insights with me. That’s what I joined these groups for, to learn from other scholars. I could teach white masculinity all day but that’s not really helpful if we want to grow. Thanks again.” This single comment from the OP received more support than we did. Another response said that we—the authors of this piece—are a “disgrace for everything academia [is] built for.” This individual’s comment also received more support than the three of us received combined.

The rest of the comments are too lengthy and numerous to list them all here but it is notable that the OP responded to the comment above with, “thank you. I’ve found people like [the authors of this piece] on multiple communication professionals fb [Facebook] pages. It’s very disheartening and scary. [….] It’s fine, those people [the authors of this piece] will get it back in some other way. And if not, we all saw it and know who the a-holes are.”

Let us put the OP’s fear and the collective anger of these 134 individuals in perspective. We wrote from a space of frustration and exhaustion regarding not only their erasure of our culture and scholarship, but also their calling upon us to do their work for them. Latinx media is mainstream. Even if the representation is not always what we would like, Latinx entertainers and entertainment have been a part of the mainstream for decades, with actresses and actors like Dolores del Rio, Rita Moreno, Edward James Olmos, Luis Guzmán, John Leguizamo, Jennifer Lopez, Eva Longoria, Danny Trejo, and many others, and movies like Selena, Desperado, Spy Kids, Machete, Dora the Explorer, and others receiving blockbuster promotions and significant box office success. Latinx media studies as well has been around for decades, with scholars like Hector Amaya, Charles Ramírez Berg, Bernadette Calafell, Isabel Molina-Guzmán, Angharad Valdivia, and many other prominent individuals. From the perspective of this erasure of a century of Latinx film representation and over three decades of Latinx media scholarship, and the OP’s hubris in believing they could teach about Latinx masculinity without having ever experienced or engaged our culture and scholarship, our responses of “How?”, “Right?”, and “confused by the difficulty” are quite frankly restrained. Nonetheless, even after the OP received the support of 134 individuals—with many calling us “nasty,” a “disgrace,” “assholes,” “elitist,” and simply unreasonable—the OP speaks of being disheartened and scared by our response.

We are compelled to interpret the OP’s public performance of fear and righteous indignation as what Barbara Applebaum terms the “active performance of [white fragility as] invulnerability” (862). As Applebaum argues, “white fragility is a form of racial violence” because, as a performative enactment of invulnerability, its objective is to protect the self from “harm and suffering, [and] to pursue safety measures that will counter the possibility of being vulnerable” (869). We see this in the OP’s response to our frustration with their public reply to one of their supporters that the authors of this piece “will get it back in some other way. And if not, we all saw it and know who the a-holes are.” That no one publicly condemned this call for collective violence against three scholars of color on the FB page of a 4,000 strong group with a claimed commitment to anti-discriminatory work speaks to the power of white fragility.

The power of white fragility is that it works to position white perpetrators as innocent victims in need of comfort and people of color “who offer antiracist critique […] as ‘angry’” offenders who threaten antiracist solidarity (Applebaum 865). “In other words,” Applebaum continues, “white comforting becomes the mechanism by which white women can avoid confronting their complicity in racism and whereby power inequities in the organization can be maintained” (865). Indeed, white fragility, including falsifying emotions and victimization, has historically (and contemporarily) been utilized to accuse, vilify, and kill people of color (Ore). It fabricates non-existent threats to manipulate others into collective violence. One must understand this historical gender and racial context of victimhood and performative allyship to fully understand the consequences of white fragility for people of color, whether those spaces are openly hostile or possess the veneer of inclusion, diversity, equity, access (IDEA), and dare we say, justice.

This is again true of our experiences, for in the moment we critiqued the nature of the OP’s request, the three of us who previously operated as distinct individuals with no prior relationship—a graduate student, recently tenured professor, and senior professor—were collectively ostracized as “assholes” who are “a disgrace to everything academia is built for.” Whereas 134 people came out in public support of the OP, and emphasized the special protections owed to her and other students, no one spoke of any special protections owed to the student of color co-author of this paper, whom was told “fuck you both” by the OP, whom was called a “disgrace,” “asshole,” “elitist,” who “will get it back some other way,” and witnessed 134 people rally against us in support of the OP. No one noticed when this student of color quietly left the group.

Postscript

One week later, at the behest of one of the authors of this piece, the admins of the Communication Scholars for Transformation posted a response to the events described above:

Though we understand that the statement was well-intentioned, the authors of this piece had hoped for much more. The admins—many of whom we know and respect—responded to the event by laying out the principles needed for a “good faith” dialogue to occur. But that good faith had already been breached by numerous members of CST: the OP when they said “fuck you both”; the senior scholar of color who came to the defense of the OP and chastised us for talking “down” to the OP and making “them feel bad”; the commenters who called us assholes, elitists, disgraces; and the 134 people who came in support of the OP without consideration of the racialized contexts and sources of our frustration. When that good faith has been breached, then a neutral response only has the effect of creating a false equivalence of “both sides” at best, or absolving the offending party of any responsibility at worst. Moreover, as Nina M. Lozano-Reich and Dana L. Cloud have argued, appeals to civility assume no power imbalance, and further operate as forms of hegemony to silence those on the margins. This may be why the admin’s post received 149 likes, from many of whom had only one week earlier come out in public support of the OP—including the OP herself, the senior scholar of color, and those who had publicly called us assholes, elitists, and disgraces to the discipline.

In closing, we are reminded of bell hooks’ writing on the politics of the racial encounter. Reflecting on the film Without You I’m Nothing, and its positioning of Blackness as “a personal metaphor for being on the outside,” hooks writes: “like her entertainment cohort Madonna, [white actress Sandra] Bernhard leaves her encounters with the Other richer than she was at the onset. We have no idea how the Other leaves her” (italics added, 380). Reflecting on our experiences: we know that white members of social movements leave their encounter with the Other richer than they had at the onset. We now know how the Other leaves the movement.

Endnotes

- We understand that some—including the other authors of this paper—may have interpreted our “F” as shorthand for profanity. Be this as it may, as we explain in the analysis that follows, none of the OP and group’s actions towards us is justified by the (possible) misunderstanding of this message. As Stuart Hall argues in Encoding/Decoding, “No doubt some total misunderstandings […] do exist. But the vast range must contain some degree of reciprocity between encoding and decoding moments, otherwise we could not speak of an effective communicative exchange at all” (“Encoding” 515). This is to say that what matters is not whether one of us used profanity towards the OP—which we did not—but rather that the OP believed that an appropriate response to our (in this case) imagined frustration towards them, was that of “Fuck you” (as documented in the following sentences). return

- Indeed, on March 17, 2021 at 10:29 PM, just hours after the OP told us “Fuck you both,” one of the authors of this paper sent a private Facebook message to the OP apologizing for any miscommunication, stating: “I want to apologize for my comment. It wasn’t meant to insult you or your work in any way. In mainstream media it seems that all there is are representations of Latinos masculinity (particularly toxic machismo). I echo the scholars [who commented on the OP’s thread] who provided their examples.” The OP would not respond three days later on March 20, 2021 at 5:41 PM. Though the OP would express appreciation for having been contacted, at no point did they apologize privately or publicly for their behavior nor the subsequent events (of which they had endorsed and encouraged). Indeed, this private message was sent two days after the OP called us “nasty,” “a-holes,” who “will get it back in some other way.” return

- The full text of the Communication Scholars for Transformation Facebook “About” reads: This group is now a PUBLIC one. Based on the previous goals articulated here, we have identified the following as salient topics of conversation going forward: 1. Develop and implement diversity and inclusion strategies in the communication field writ large. 2. Initiate collaborative initiatives on diversity and inclusion outside the field’s professional organizations. 3. Provide support for colleagues on the margins. If you would still like to sign the open letter in response to the recent editorial drafted by Marty Medhurst, letters drafted/endorsed by NCA Distinguished Scholars, and broader concerns regarding diversity and social justice in our discipline, please follow this link: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSfMyosNWkZvTu7TK5JsZxx4bpYO_vJp_3f2ERozw5QWnaJN8w/viewform?fbclid=IwAR0uuI6cOxyH_2Xp5I0sYrMZQYMCyWF-Qn4jqbbaAY8V3pAasnfmbL8zaog =============== Greetings! This page is designed to facilitate signatures to an open letter in response to the recent editorial drafted by Marty Medhurst, letters drafted/endorsed by NCA Distinguished Scholars, and broader concerns regarding diversity and social justice in our discipline. Please follow the link in the discussion section to add your name. (Communication Scholars for Transformation, About) return

- This percentage is approximate and calculated based on the closest membership estimate we have for the date of the event—which is a screenshot documenting 3,891 members on May 20, 2021 (two months after the incident). In the two months since that screenshot was taken, the group has added 142 members. Even if we were being incredibly generous, and assumed that the group added 891 members between March 17 and May 20 (or over six times the amount of new members added between May and July), the ratio of support for us is only marginally affected (from 0.1285% [of 3,891] to 0.1667% [of 3,000]). return

- Related to our prior note, this percentage is approximate and calculated on the basis of the group’s May 20, 2021 membership total of 3,891. return

Works Cited

Applebaum, Barbara. “Comforting Discomfort as Complicity: White Fragility and the Pursuit of Invulnerability.” Hypatia 32.4 (2017): 862-75.

Calvente, Lisa B. Y., Bernadette Marie Calafell, and Karma R. Chávez. “Here Is Something You Can’t Understand: The Suffocating Whiteness of Communication Studies.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 17.2 (2020): 202-09.

Communication Scholars for Transformation. “About.” https://www.facebook.com/groups/457629181722810/about

DiAngelo, Robin. “White Fragility.” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 3.3 (2011): 54-70.

Gutiérrez y Muhs, Gabriella, Yolanda Flores Niemann, Carmen G. González, and Angela P. Harris. Presumed Incompetent: The Intersections of Race and Class for Women in Academia. Boulder, CO, Utah State University Press, 2012.

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding, Decoding.” Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks. Eds. Durham, Meenakshi Gigi and Douglas M. Kellner. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 1973/2012. 507-17.

—. “Gramsci’s Relevance for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 10.2 (1986): 5-27.

—. “What Is the “Black” in Black Popular Culture?” Black Popular Culture. Ed. Dent, Gina. New York: The New Press, 1983. 21-33.

Harris, Cheryl. “Finding Sojourner’s Truth: Race, Gender, and the Institution of Property.” Cardozo Law Review 18 (1996): 309-409.

hooks, bell. “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance.” Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks. Eds. Durham, Meenakshi Gigi and Douglas M. Kellner. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 1992/2012. 308-18.

Lozano-Reich, Nina Maria and Dana L. Cloud. “The Uncivil Tongue: Invitational Rhetoric and the Problem of Inequality.” Western Journal of Communication 73.2 (2009): 220-226.

Mejia, Robert. “Forum Introduction: Communication and the Politics of Survival.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 17.4 (2020): 360-68.

Martínez, Diana Isabel. “Archival Impulses: Rhetorics of Nepantla, Memory, and the Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa Archives.” Lanham, MD, Lexington Books, 2022.

Moffitt, Kimberly R., and Heather E. Harris. “The Imperatives of Community Service for Afrocentric Academics.” Journal of Black Studies 34.5 (2004): 672-85.

Ore, Ersula. “Lynching: Violence, Rhetoric, and American Identity.” Jackson, MS, University Press of Mississippi, 2019.

Pierce, Chester. “Is Bigotry the Basis of the Medical Problem of the Ghetto.” Medicine in the Ghetto. Ed. Norman, John C. Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, 1969. 301-14.

Phipps, Alison. “White Tears, white rage: Victimhood and (as) violence in mainstream feminism.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 24.1 (2021): 81-93.

Sowards, Stacey K. “Constant Civility as Corrosion of the Soul: Surviving through and Beyond the Politics of Politeness.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 17.4 (2020): 395-400.

Sue, D. W., et al. “Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice.” Am Psychol 62.4 (2007): 271-86.

Sue, Derald Wing, et al. “Disarming Racial Microaggressions: Microintervention Strategies for Targets, White Allies, and Bystanders.” American Psychologist 74.1 (2019): 128-42.

Valdivia, Angharad N. “Amnesia and the Myth of Discovery: Lessons from Transnational and Women of Color Communication Scholars.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 10.2/3 (2013): 329-32.

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: Robert Mejia. This image was created by isolating the woman of color at the center of the photo and applying a dark strokes filter, then a black and white filter and sponge filter was applied to the remainder of the image. Photo Credit: Oneinchpunch/Canva. Original Photo Title: Activists Demonstrating Against Social Issues.

KEYWORDS: white fragility, politics of summoning, collective violence, microaggressions, whiteness

Robert Mejia is the Communications Manager at A New Way of Life Reentry Project. His work focuses on transforming the narrative surrounding incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and systems-impacted communities, especially regarding women and LGBTQ communities. His research interests span the intersections of media, technology, race, class, and gender, and has appeared in outlets such as Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, Critical Studies in Media Communication, Rhetoric of Health and Medicine, and other venues. He is the past recipient of the 2018 National Communication Association’s Critical and Cultural Studies Division's (CCSD) New Investigator Award and the 2019 CCSD Outstanding Article Award.

Robert Mejia is the Communications Manager at A New Way of Life Reentry Project. His work focuses on transforming the narrative surrounding incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people and systems-impacted communities, especially regarding women and LGBTQ communities. His research interests span the intersections of media, technology, race, class, and gender, and has appeared in outlets such as Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, Critical Studies in Media Communication, Rhetoric of Health and Medicine, and other venues. He is the past recipient of the 2018 National Communication Association’s Critical and Cultural Studies Division's (CCSD) New Investigator Award and the 2019 CCSD Outstanding Article Award.  Nina Maria Lozano is an Associate Professor with the Department of Communication Studies at Loyola Marymount University. She received her Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her work has been published in Communication Quarterly, Western Journal of Communication, Text and Performance Quarterly, and numerous other academic outlets. She is a regular contributor to the Huffington Post, and other political public outlets and news media. Her most recent publication, Not One More! Feminicidio on the Border, published with the Ohio State University Press, has received stellar reviews. Her current book project extends this work by examining feminicidio and gendered asylum.

Nina Maria Lozano is an Associate Professor with the Department of Communication Studies at Loyola Marymount University. She received her Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her work has been published in Communication Quarterly, Western Journal of Communication, Text and Performance Quarterly, and numerous other academic outlets. She is a regular contributor to the Huffington Post, and other political public outlets and news media. Her most recent publication, Not One More! Feminicidio on the Border, published with the Ohio State University Press, has received stellar reviews. Her current book project extends this work by examining feminicidio and gendered asylum.  Ariana Cano is a doctoral student in the Institute of Communication Research at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She graduated from California State University of San Bernardino with an MA in communication studies (2018) and was awarded the Outstanding Graduate Student and Teaching Associate in her department. Her work focuses on how Chicana and Indigenous communities (particularly womxn) use social media to challenge matrices of domination (white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, capitalism, settler colonialism) and create opportunities of personal, communal, and civic value. Ariana was recently accepted as the 2021 Student Scholar for the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity (NCORE).

Ariana Cano is a doctoral student in the Institute of Communication Research at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She graduated from California State University of San Bernardino with an MA in communication studies (2018) and was awarded the Outstanding Graduate Student and Teaching Associate in her department. Her work focuses on how Chicana and Indigenous communities (particularly womxn) use social media to challenge matrices of domination (white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, capitalism, settler colonialism) and create opportunities of personal, communal, and civic value. Ariana was recently accepted as the 2021 Student Scholar for the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity (NCORE).