Art and Heart to Counter the One-hour-Zoom-diversity Event: Counterspaces as a Response to Diversity Regimes in Academia

This article outlines the development of a community arts-based project as a counterresponse to the gaps in ongoing institutionalized Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) efforts on our campus and our mutual recognition of the emotional support we provide Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC) students. Contrary to what has been the current approach of creating a racially progressive university campus, such as the implementation of new institutional policies (Kezar 2007), an increase in the representation of diverse students, faculty, and staff (Hale 2004), or changes in organizational practices (Rothman, Kelly-Woessner, and Woessner 2010), critically-minded scholars and practitioners still see DEI initiatives, practices, and programming in higher education as ineffectual and counterproductive (Thomas 2017; Ahmed 2009; Okuwobi, Faulk, and Roscigno 2021; Oliha-Donaldson 2018; Cabrera 2020). We argue that the spaces, strategies, and practices that might allow BIPOC faculty and students to thrive and imagine futures need to stay separate from institutional DEI efforts. We draw on Thomas’ definition of diversity regimes as “a set of meanings and practices that institutionalizes a benign commitment to diversity …[which] entrenches, and even intensifies existing racial inequality” (2017, 141) to contextualize our experiences as faculty of color at a health sciences campus in the Midwest.

Our praxis is also heavily influenced by Yosso, Solorzano, and others’ concept of Counterspaces (Solorzano and Yosso 2001; Yosso 2013; Yosso and Lopez 2010), which are spaces built and maintained by marginalized individuals to find support and develop strategies of survival in unwelcoming social environments. Using reflective vignettes, we show how this collective arts-based project was our counterresponse to our campus’ diversity regime and lack of substantial resources and support for BIPOC students. Due to space constraints, this article only examines the development of a counterspace using art and anti-racism pedagogy and praxis via group workshops. Thus, we invite the reader to immerse and engage with both the written and visual creations of our BIPOC student-artists by going to our public page at www.counterspacesart.com. On this site, you will find a digital archive of visual and written artwork as exhibited at Rochester Art Center, our local museum. Each student piece came to completion via workshop activities, personal exchanges, and emerging mentoring relationships that comprised this counterspace. As an ever-evolving archive, the site will continue to incorporate artistic creations that have emerged from the initial iteration of this project.

Space Invading: Brown in the Midwest

Our positionality influenced the nurturing of a counterspace to support BIPOC students and critique of DEI regimes. We are both faculty at the University of Minnesota Rochester (UMR), a campus connected to an institutional consortium of campuses comprising the University of Minnesota system. About 40% of our students self-identify as BIPOC; in contrast, people of color represent ten percent of the total number of faculty. As faculty of color, we are not only tasked with teaching, research, and service, but find ourselves supporting BIPOC students emotionally while being expected to volunteer our expertise to meet the needs of our institution’s diversity regimes. As “space invaders”—a term by Puwar (2004) to illustrate how minoritized individuals experience inhabiting spaces where they do not fulfill the embodied ideal (in this case, white, often cisgendered male) of these spaces—we are raced and gendered in uniquely distinct ways that shape how we “invade” various spaces and are perceived by others. For example, we have noted the ways stereotypes about working-class Latina femininity influence how some might label Angie as “difficult” and “too passionate” (See Niemann 1999; Saldana, Castro-Villarreal, and Sosa 2013, for more on Latina faculty experiences in the academy). Alternatively, Yuko’s positionality as a 1.5 generation Japanese woman faculty might invoke gendered and racialized stereotypes of Asian women as passive and non-confrontational (Le Espiritu 2008; Pyke and Johnson 2003), which might put many white Midwesterners at ease (see Turner, Myers Jr, and Creswell 1999, for faculty of color in the U.S. Midwest; see Mayuzumi 2008, for work on Asian women faculty). This engagement with and analysis of our space invader statuses also highlight our use of embodied strategies “to counter hegemonic narratives of bodily misrecognition within White, privileged academic social spaces” (Ford 2011, 448). Thus, it is this shared experience of being misrecognized which has also influenced our critical responses (often read by many of our colleagues and members of our campus leadership as resistance) to UMR’s ongoing diversity efforts and how we have learned to support each other and our students.

Art and Heart

Whose Truth? Whose Space?

I’m attending UMR’s February’s one-hour-Zoom Diversity Dialogues. Advertised as a dedicated space for BIPOC students to share their perspectives and for others to learn and support, we begin hearing Black students describe the nature of embodied racial vulnerability in Minnesota. A few more minutes pass, and facilitators are now spending a significant amount of time dealing with a white student who insisted on explanations for the links between racism and police brutality. We are nearing the end of this event when our DEI administrator makes sure to personally thank the student for “sharing [their] truth.”

—AM

Our experiences suggest not only that many white students at UMR] are ill-prepared to dwell in discomfort; DEI programming tends to cater to their comfort and fragility. Once again, the space provided by Diversity Dialogues was dedicated to white students and staff, forgetting the need for BIPOC students to share their perspectives. Since they have yet to provide a transformative space for dialogue, we attend these chats to signal to the BIPOC students our availability to debrief and share what they could not feel comfortable saying.

Moving Mountains

I’m writing a strange poem about mountains made of butterflies. I honestly don’t have the time to be writing a poem. I still have a lot of reflection papers to grade. Earlier, I told my colleague, Katie Cullen, a faculty at the Twin Cities’ campus, that I had to do something. Just two days ago, six Asian women were shot in Atlanta. Hate crimes and violence against AAPI have already been increasing during the pandemic. I’ve been reaching out to my AAPI students. Many said they were scared and angry and exhausted from feeling scared and angry. Our physical appearance can prompt intense hatred in some people. Those people want to push, punch, and kill us. Could this happen to them or their families here in Minnesota? They know the answer: yes, yes, and yes.

—Yuko

Amid these feelings of hopelessness and the emotional exhaustion of supporting some of our Asian students, I remembered Akiko Yosano’s poem from the early 1900s, “The Day the Mountains Move” (1957). I am struck by the last two stanzas—“All the sleeping women/Are now awake and moving.” Sharing this poem with Katie, I wondered how Yosano held such a strong thought back when women had no authority in Japan. How did she find the voice to speak, even if no one believed her? Katie said she got chills from the image of the poem: all the sleeping women are now awake and moving. But I still need to callthe pharmacy back to be placed on the vaccine waiting list. But I also know myself. I won’t sleep unless I write down this image of butterflies shifting the shape of mountains. This image feels exciting to me, like strength or hope. As I’m staying up late, writing this poem as a response to Yosano, I want to see what moving mountains look like.

Truth of Mountains: Art, Space, and Place

What can we do to heal? Is this the time to rest, or is this the time to connect, share our thoughts, and pour our energy into creating something? I can’t always tell what we need, and the only way to find out is by doing. Art is about doing. I exchange some texts with Angie with a vague idea of organizing a gathering. I know that many BIPOC students have been reaching out to her. What if they are given a creative outlet to express their thoughts openly and honestly? A is immediately excited. I don’t exactly know the details of how we need to move forward. But Katie’s chills and Angie’s excitement are telling me that we need to connect.

—Yuko

We have learned from our BIPOC students about the lack of opportunities to discuss issues relevant to their identities as “space invaders,” lest these are open to the rest of the campus community. At the time of writing, the only spaces for students to discuss issues at the societal level were those provided by Diversity Dialogues. Thus, our task would be to nurture a space while making visible the multiple and complex ways these students experienced being othered on this campus, in the Midwest, and as future health science professionals. We also needed to support them without immediately burning ourselves out, so the project needed to tie into our research and teaching agendas.

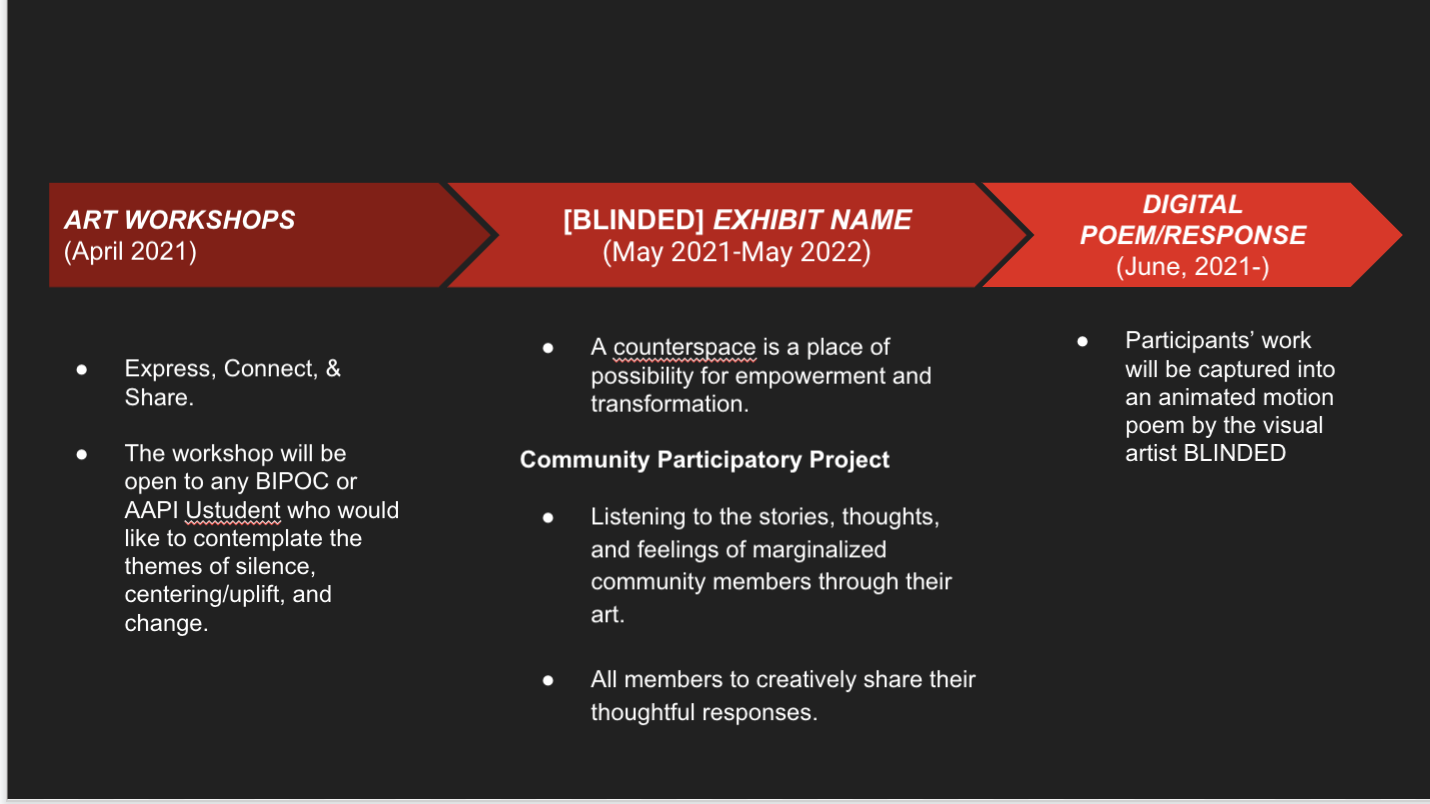

Open to BIPOC students from any of the Universitty of Minnesota system campuses, the project would have three parts—reflective workshops focusing on anti-racism praxis and artistic creation, a public exhibit centering these students’ written and visual artwork, and a digital art motion poem by a visual artist (in response to the students’ creations) once the public exhibit is complete and fully archived in the Counterspaces’ website. Figure 1 (below) depicts a timeline of these interrelated parts (workshops, museum exhibition, and ongoing digital efforts, including archiving) as initially advertised to participants.

To highlight the project as a counterspace for BIPOC students and counterresponse to UMR’s DEI regimes, we decided that the artistic work would need to reach beyond the campus’ walls. Yuko contacted Zoe Cinel, curator at the Rochester Art Center, asking her for a small, temporary space to display some of the pieces. She and the museum staff designed a year-long exhibition area with a rotation of the artwork created in each workshop. Along with Yuko (depicted in the image below), museum’s staff designed a spot on the third floor with seats to invite patrons to contemplate and two additional art stations stocked with supplies to write messages of support or create artwork in response to the exhibit.

The workshops provided a rare moment for many student-participants to feel comfortable sharing their perspectives about being part of a sizeable population of BIPOC and yet being rendered outsiders, somewhat isolated from the broader campus community. For example, during one of our workshops, a participant mentioned the contrast between the visible number of religious Black Muslim students and the university’s lack of space for purification and prayer. Angie had previously learned that some of the students offered their on-campus apartments (going as far as providing copies of keys) to their off-campus peers as a dedicated space to pray. The exhibit and one of the artists, to date, have been featured on the local news. In addition to plans with other campuses to coordinate similar counterspaces-based initiatives, we have planned an upcoming public engagement opportunity (workshop with artwork creation, exhibition, and digitalization) for members of the local community that self-identify as BIPOC and another set of workshops geared to BIPOC medical students.

Pushing Back

UMR student services’ staff has Zoomed-in to discuss if we could deliver the workshops to incoming first-year students. Yuko is Zooming in from her home office. Some of the artwork for one of her future exhibits is visible. As usual, I am silent and with my camera off. (Yuko and I agreed on this dynamic early on: she engages with people first since I have the rare talent of jarring Midwesterners into a further state of discomfort.) Yuko reminds them that workshops are only open to BIPOC students and that we will need to be compensated for any work we do during the summer. “Is there something that can be done for ALL students?” (They forgot to mention, unpaid.) “Like a guided tour to highlight our campus’ BIPOC community.” While the museum exhibit is open to the public, Yuko suggested that students be introduced to anti-racism praxis basics to understand the guided tour. I doubt Yuko is getting through to them. In exasperation, I turn on my camera and blurt out, “You seem to think the exhibit is all about pastels and poems and flowers. It. Will. Make. White. Students. Uncomfortable.” [I clap after each word to emphasize this last remark.] There was a moment of silence before we moved to the similarly awkward ritual of saying goodbye.

—Angie

This last reflection highlights one of the many times we have found ourselves as part of some “Good Cop, Bad Cop” performanceto protect the project from being co-opted under UMR’s diversity regime. For example, an administrator suggested that the workshops should be reworked as an “all-staff diversity training,” and it became uncomfortable when I moved to discuss compensation. As Lerma and colleagues have noted, institutional requests for “racialized equity labor” (2020), that is, the work expected of minoritized staff, faculty, and students as part of institutional diversity regimes, tend to be connected to programming and initiatives that have little to no effect on equity matters.

Discussion: Art+Counterspaces as Praxis and Futures

How does one make a counterresponse to DEI regimes strategically and intentionally visible? For us, we emphasize how the project would not be just a “safe space” for BIPOC students or an additional institutional DEI initiative. The workshops, exhibits, and future digital projects have emerged as a counterspace because of the lack of places on campus, material or otherwise, for our BIPOC students to feel like they truly belong. This is central to every email, discussion, and grant application connected to the project. The message is also in the counterspace’s existence in a place like Minnesota, where racially privileged citizens struggle to reckon with the effects of their “Minnesota Nice” avoidance of racial and similar injustices. Thus, part of nurturing a counterspace for racially minoritized groups to think of new practices is to prevent it from becoming one more diversity display, an “activit[y] centered around the inclusion of heterogeneous groups even if [it is], more or less, divorced from positive or desired outcomes.” (Okuwobi, Faulk, and Roscigno 2021, 3)

The idea of creating or maintaining spaces in the margins to survive precarious and hostile environments is not new. However, finding ways to make these practices visible and intentional enough to communicate where diversity regimes in higher education fail might be new. Our task was to demonstrate how community-based art can serve as a constant critique, highlighting the gaps and limitations of current diversity initiatives on our campus. We believe that BIPOC futures in academia will be found in those practices, spaces, and places that run counter to those connected to diversity regimes. This article highlighted steps we took as we envisioned praxis and space- and place-making via counterspaces. Our digital archive site www.counterspacesart.com includes documentation of our process (including creative writing prompts used in the workshops) for others to replicate and modify. By sharing our model, we hope that we can open up a conversation on strategies to design and sustain spaces and practices that can run parallel to existing efforts that maintain the institutional status quo of systemic forms of oppression.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. 2009. “Embodying Diversity: Problems and Paradoxes for Black Feminists.” Race Ethnicity and Education 12 (1): 41–52.

Akiko, Yosano, and Heihachirō Honda. 1957. The Poetry of Yosano Akiko. Hokuseido Press.

Cabrera, Nolan L. 2020. “‘Never Forget’ the History of Racial Oppression: Whiteness, White Immunity, and Educational Debt in Higher Education.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 52 (2): 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2020.1732774.

Ford, Kristie A. 2011. “Race, Gender, and Bodily (Mis) Recognitions: Women of Color Faculty Experiences with White Students in the College Classroom.” The Journal of Higher Education 82 (4): 444–78.

Hale, Frank W. 2004. What Makes Racial Diversity Work in Higher Education: Academic Leaders Present Successful Policies and Strategies. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Kezar, Adrianna J. 2007. “Tools for a Time and Place: Phased Leadership Strategies to Institutionalize a Diversity Agenda.” The Review of Higher Education 30 (4): 413–39.

Le Espiritu, Yen. 2008. Asian American Women and Men: Labor, Laws, and Love. Rowman & Littlefield.

Mayuzumi, Kimine. 2008. “‘In‐between’ Asia and the West: Asian Women Faculty in the Transnational Context.” Race Ethnicity and Education 11 (2): 167–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320802110274.

Niemann, Yolanda Flores. 1999. “The Making of a Token: A Case Study of Stereotype Threat, Stigma, Racism, and Tokenism in Academe.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 20 (1): 111–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346994.

Okuwobi, Oneya, Deborwah Faulk, and Vincent J Roscigno. 2021. “Diversity Displays and Organizational Messaging: The Case of Historically Black Colleges and Universities.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1–17.

Oliha-Donaldson, Hannah. 2018. “Let’s Talk: An Exploration into Student Discourse about Diversity and the Implications for Intercultural Competence.” Howard Journal of Communications 29 (2): 126–43.

Puwar, Nirmal. 2004. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies out of Place. London, UK: Berg.

Pyke, Karen D., and Denise L. Johnson. 2003. “Asian American Women And Racialized Femininities: ‘Doing’ Gender across Cultural Worlds.” Gender & Society 17 (1): 33–53.

Rothman, Stanley, April Kelly-Woessner, and Matthew Woessner. 2010. The Still Divided Academy: How Competing Visions of Power, Politics, and Diversity Complicate the Mission of Higher Education. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Saldana, Lilliana Patricia, Felicia Castro-Villarreal, and Erica Sosa. 2013. “‘ Testimonios’ of Latina Junior Faculty: Bridging Academia, Family, and Community Lives in the Academy.” Educational Foundations 27: 31–48.

Solorzano, Daniel, and Tara Yosso. 2001. “Critical Race and LatCrit Theory and Method: Counter-Storytelling.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 14 (4): 471–95.

Thomas, James M. 2017. “Diversity Regimes and Racial Inequality: A Case Study of Diversity University.” Social Currents 5 (2): 140–56.

Turner, Caroline Sotello Viernes, Samuel L Myers Jr, and John W Creswell. 1999. “Exploring Underrepresentation: The Case of Faculty of Color in the Midwest.” The Journal of Higher Education 70 (1): 27–59.

Yosso, Tara. 2013. Critical Race Counterstories along the Chicana/Chicano Educational Pipeline. Routledge.

Yosso, Tara, and Corina Lopez. 2010. “Counterspaces in a Hostile Place.” Culture Centers in Higher Education: Perspectives on Identity, Theory, and Practice, 83–104.

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: Picture by Angie Mejia and Yuko Taniguchi.

KEYWORDS: Counterspaces, arts-based research, pedagogy and praxis, diversity regimes, BIPOC in the academy

Angie Mejia, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor and Civic Engagement Scholar at the Center for Learning Innovation at the University of Minnesota Rochester. Trained as a sociologist and feminist methodologist, her research uses intersectional analyses, critical participatory methods, and cross-community collaborations to study mental health inequities in historically marginalized communities of color. Her scholarly work has appeared in several academic journals, including Action Research, Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research (SPUR), Anthropologica, and Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies.

Angie Mejia, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor and Civic Engagement Scholar at the Center for Learning Innovation at the University of Minnesota Rochester. Trained as a sociologist and feminist methodologist, her research uses intersectional analyses, critical participatory methods, and cross-community collaborations to study mental health inequities in historically marginalized communities of color. Her scholarly work has appeared in several academic journals, including Action Research, Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research (SPUR), Anthropologica, and Cultural Studies <-> Critical Methodologies.  Yuko Taniguchi, M.F.A., is the author of a volume of poetry, Foreign Wife Elegy (2004), and a novel, The Ocean in the Closet (2007), published by Coffee House Press. Her awards include finalist for The Dayton Literary Peace Prize, the Kiriyama Prize Notable Book, the Gustavus Myers Center Outstanding Book Award Advancing Human Rights, and the McKnight Artist Fellowship for Writers. Taniguchi is an instructor of Writing at the University of Minnesota Rochester. She is also a founding faculty for Mayo Clinic Humanities in Medicine Arts at the Bedside-Creative Writing Program. Taniguchi is a recipient of a 2016 Bush Fellowship. She is an artist in residence in the Department of Medicine at the University of Minnesota and Weisman Art Museum for the project, Target Studio for Creative Collaboration.

Yuko Taniguchi, M.F.A., is the author of a volume of poetry, Foreign Wife Elegy (2004), and a novel, The Ocean in the Closet (2007), published by Coffee House Press. Her awards include finalist for The Dayton Literary Peace Prize, the Kiriyama Prize Notable Book, the Gustavus Myers Center Outstanding Book Award Advancing Human Rights, and the McKnight Artist Fellowship for Writers. Taniguchi is an instructor of Writing at the University of Minnesota Rochester. She is also a founding faculty for Mayo Clinic Humanities in Medicine Arts at the Bedside-Creative Writing Program. Taniguchi is a recipient of a 2016 Bush Fellowship. She is an artist in residence in the Department of Medicine at the University of Minnesota and Weisman Art Museum for the project, Target Studio for Creative Collaboration.