Public Marginalia: (Re)Markable Conversations (Re)Surfacing and (Re)Buffed

Annotated transcript for the video essay:

The AUTHOR marks and reads text from H. J. Jackson’s article “Writing in Books and Other Marginal Activities”:

“Marginalia are conventionally responsive, personal (though anonymous), critical (in the sense of evaluative), and economical. They respond to an antecedent text; . . .”

The AUTHOR interrupts himself.

Text . . . Mmmm . . . Maybe con/text . . . Yeah. All right, let’s see:

“they express the separate (usually contrary) views of the marginalist, and thereby assert a separate personality; they make a critical appraisal of the original statement; and they must do it economically because of the physical constraints of margins” (219).

Yeah . . .

The AUTHOR tries to annotate the text but discovers he has very little room to do so.

Wait. Shit.

He writes “Yes!” on the very narrow right-hand margin.

The AUTHOR writes the TITLE of the episode, “Public Marginalia: (Re)Markable Conversations (Re)Surfacing and (Re)Buffed,” on the article and on Post-its. We fly into one particular word at the end: margins.

Just as book historian Heather Jackson attests to here, . . .

The ANNOTATED PAGES of an opened book move through a tunnel.

I am also drawn to the margins: I am drawn, though, away from the pages of a book and into those margins emerging from the shadows of brick and concrete and steel, of places that are out of place, on whose surfaces we play in other embodied ways: walking and creeping and scratching into the nooks of an urban alleyway, behind the back of an abandoned building, along the gravel of an unwatched train yard, and deep inside the viscera of a dark tunnel.

AUTHOR marks and reads text from Jean Baudrillard’s article “Kool Killer.” A second voice, then a third, interject and read along—and against—the author’s. We focus on one word spray-painted into a stencil: scream.

They are the marks of those who Jean Baudrillard says “burst into reality like a scream, an interjection, an anti–discourse, as the waste of all syntactic, poetic, and political development, as the smallest radical element that cannot be caught by an organized discourse” (78).

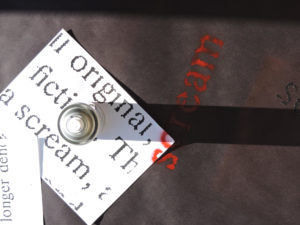

A PAINT CAN watches on, producing a shadow along the word scream, pointing to a text from Ralph Cintron’s chapter from Angels’ Town. Another shadow flips through tighter frames of a single, pixilated word: shadow.

Such anti-discourse emerges from the shadows and, in the words of Ralph Cintron, become themselves shadows, shadows of a system world; “the system world” he says, “is the ‘substance’ that casts the shadow, a shadow that has the shape but is not equivalent to the system itself. The result is that the shadow system mimics the system world through many appropriations of and improvisations upon the system world’s material” (176).

We pull into Cintron’s text, narrowing in on the word shadow.

We have then voices from the margins appropriating the organized behaviors and discourse of the system world, improvising upon the surfaces of that world in order to form their own shadows. The shadows mimic but resist organized behavior and discourse by shifting them into something unsanctioned, unexpected, as the shadows dance and play in the margins.

The word scream reappears, dancing across the word shadow.

The mimetic shadows of graffiti, then, encourage their writers to scream, to interject their own subjectivities through “tactics of language”—a concept Cintron develops as he discusses gang graffiti:

The AUTHOR marks another of Cintron’s passages, joined by another voice: It’s “an important narrative ‘tactic’ available to gang members for the public expression of their subjectivities, subjectivities that were constantly being suppressed by the public sphere” (176)—that is, the public sphere of the system world.

Montage of graffiti, of “tactical interjections,” ending at a sign posted: NO TRESPASSING.

These tactical interjections can become public rhetorics that to the unknowing eye seem to have little outward purpose beyond marking that someone was there, those marks that are inscribed on unsanctioned surfaces, performed through unsanctioned behavior—performances I call public marginalia.

Public marginalia can take place anywhere, of course, but it’s their urban margins that I like to explore most: an abandoned building in New Orleans, for example, sits next door to a building owner who’s got their own message to convey; the back of a street sign in Austin that plays mediator for competing grassroots and guerrilla marketing; some construction scaffolding near the 9/11 memorial in downtown Manhattan—all invisible everyday spaces that reflect, reclaim, but resist the discourse of the system world.

DEBRIS and BRICKS appear, with the word unremarkable spray-painted across some of the bricks.

They are, as Cathryn Molloy might say, “generative sites where unremarkable underlife public writings emerge” (19). Molloy develops the idea from Robert Brooke, who calls underlife “those behaviors which undercut the roles expected of participants in a situation” (141).

A broken word unremarkable sits along four bricks. The AUTHOR further breaks and refashions the word to form remarked.

Emphasizing and breaking apart the word “unremarkable” reveals a use for looking at things unworthy of being responded to, unworthy of being remarked upon. Unworthy of being re-marked.

Pull back to reveal the word scream painted across other bricks just above those holding the word remarkable.

It is, however, the underlife that does re-mark that I am called to—those that prompt their writers to engage each other in interjections of competing yet mimetic subjectivities in the margins of anti-discourse.

The ANNOTATED PAGES of an opened book again move through a tunnel.

In this episode I explore one of these generative sites—a tunnel on the campus of my university, where students and a university organization re(-)mark upon each other’s marks. These are remarkable in two senses of the term: they are marks that have been erased or “buffed”—as graffers might say—by a university organization, prompting students and perhaps others to take up the second sense of the word, performing what criminologist Jeff Ferrell calls “intertextual dynamics”—marks that are written around, beside, on top of other marks that respond to each other, remarking on what’s come before, re-marking on top of what’s come before.

This remarkability confers with Jackson’s definition of “normal” marginalia.

SOUND of JACKSON QUOTE: “Marginalia respond to an antecedent text; they express the separate (usually contrary) views of the marginalist, and thereby assert a separate personality; they make a critical appraisal of the original statement; and they must do it economically because of the physical constraints of the margins.”

Her definition frames marginalia as those that grow from, talk to, or in some way engage Text that has already been shaped, judged, legitimated, and published. Jackson differentiates such annotation from other forms of responsive markings, such as graffiti, which at times can exist independently from any Text, she says, without an inspiring rhetorical situation:

AUTHOR marks another passage of Jackson’s text, read by another voice:

“Although graffiti may be conditioned to some extent by their locations—desktops, hoardings, washroom walls; although they may respond to earlier graffiti [. . . ]; and although they may be limited by custom to certain themes, graffiti have an autonomy that is denied to marginalia. They are not necessarily initiated by other texts, and they freely, without complication, displace other graffiti to foreground themselves” (219-20).

Montage of graffiti.

Graffiti scholars such as Nancy Macdonald and Jeff Ferrell agree that much graffiti is intended to be acontextual and indecipherable to those outside graffer communities, who strive to maintain their work as anonymous, private, marginal, and unsanctioned. Much graffiti, however, is contextualized, inspired by other graffiti, “initiated by other texts,” or other symbolic and material practices, even simply by the surface itself—all of which inform how an audience should be reading it and making meaning from it. There are many instances of graffiti and other forms of public marginalia that inspire conversations—through words and visuals or even simply silence.

Establishing shots of campus.

In 2010, my institution, James Madison University, completed construction of the Forbes Center for the Performing Arts, which houses the academic programs of theatre, music, and dance as well as their performance spaces. The center, along with an adjacent parking deck, was built across the street from what we call Bluestone or Old Campus, which houses many of the humanities as well as the Quad. To help folks more easily move back and forth between Old Campus and the Forbes Center and the parking deck, a tunnel was built underneath the street. The tunnel soon became a surface that drew on the artistic skills of students on this side of campus, a space that became what I’ll call a chalkscape. Here is Anne Frank:

“Whoever is happy will make others happy too. He who has courage and faith will never parish (sic) in misery.”

Beaker celebrating Pride Week:

“Haters gonna hate, lovers gonna mate.”

“The PenIs: Mightier than the Sword.”

And some other nods to popular culture.

In October 2013, a faculty- and student-sponsored organization called the Madison Society, which “seeks to create, enhance, and commemorate positive traditions at JMU,” did in fact create a new tradition for the campus when it painted each wall of the tunnel purple with a quote by the school’s namesake, James Madison, himself:

“Knowledge will forever govern ignorance.”

It’s painted top-to-bottom and side-to-side, what graffiti writers themselves call going “whole car.”

Founding member of the Madison Society, Dave Barnes, said that “The idea of putting the quote up somewhere on campus came to us and we thought, well, this is something we’d definitely be supportive of. [. . .] This is something that’s been created as another lasting landmark on campus for students, faculty, and staff to get excited about.” Some students did get excited about it but not perhaps in the positive way Barnes would’ve hoped for.

STUDENTS work at their laptops in a classroom.

A year later, one day in October 2014, a few students in my genre theory course, which had been studying a unit on graffiti, came into class asking if I had seen that the Forbes Tunnel had been tagged. We flipped the class into a field trip and headed out into the Quad and down into the tunnel.

CRAYON along the floor of the tunnel: “These walls were a place of expression.”

CHALK along the wall of the tunnel: “Now they are agian (sic). The Power of chalk overwhelms the love of qoutes (sic), this wall will be dope again. Bring the chalk back.”

We follow the quote “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance.” to its end, landing on a misplaced period.

The quote comes from a letter Madison had written to Kentucky statesman W. T. Barry in August 1822. It famously if tersely demonstrates Madison’s views on self-governance and the importance of an educated populace. The period at the end of the quote assumes that’s the end of the quote. But “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance” is followed not by a period but by a colon in the original source, suggesting a continuation of thought, that there is indeed something else to come: “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.”

Students may have been inadvertently fulfilling Madison’s wish there upon the wall in a tunnel on the literal margins of campus, performing the missing half of the quote; as their own Governors, students had indeed taken up arms with the power of crayons and chalk against what one marginalist said “the love of quotes.” Their response becomes, as communications specialist Dean Scheibel might say,

The AUTHOR marks Scheibel’s text, annotating it with students fulfilling the missing quote.

“a counter-ideology [. . .] created and [. . .] positioned against the dominant ideology of other sectional interests” (4). Students counter the dominant ideology of the first half of the quote but perhaps unknowingly shadow the counter-ideology not apparent in the missing second half of the quote. Students are responding to what is not there, mimicking the sentiment they cannot see.

Before the Madison quote went up, students had appropriated the space for what seemed like innocuous messages, written in chalk, resonating with childhood practices of scribbling and drawing on neighborhood sidewalks. And then a year later, we find students not simply chalking on the painted wall, but responding to Madison’s message, responding to the power structure they perceived shut them down in the first place.

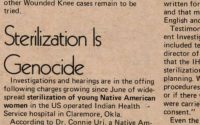

Arguably, the marks that students had drawn previously were not public marginalia as I am attempting to define it: as responses to established contexts in unsanctioned spaces. These were students who took up a space seemingly appropriate for such kinds of artistic license: a tunnel that leads to a center for the performing arts. Such uptake inspires cultural geographer Tim Cresswell to explore “a questioning of boundaries” (333), asking, who has the right to this space? In his exploration, Cresswell analyzes media reports

Montage of headlines from The New York Times.

about graffiti during its heyday in New York City 40 years ago, culling popular and political reactions to what he terms a “discourse of disorder”: “a set of descriptive terms which imply that graffiti is out of place and suggest how it might be put back in place” (329). By chalking in a performing arts tunnel, students may have thought they were adding to the atmospherics of such a space, taking advantage of marks that are already in their place. But as a more authoritative entity such as the Madison Society rebuffs students’ performances by buffing the space, their performances become out of place. It might not have been graffiti before,

Montage of student responses to the painted quote in the Forbes Tunnel.

but it is now, as the tunnel provides an intertext of ideology: of school pride, as students chant the university motto, “Be the change”; of nostalgia, heralding the return of the chalk and artwork; of popular culture; of inspiration. A political context as hot as the 2016 presidential season is encouraged some to use the dirt on the surface of the tunnel to perform reverse graffiti. Though some of the text is illegible here, the intent is clear: “Hate speech is protected in the US by the First Amendment.” One student annotated Madison’s claim with a hopeful nod to then-presidential candidate Donald Trump. We might see this as a student’s attempt at sarcasm and not actual support for Trump. But another student perhaps thought the latter and responded in kind.

The playfulness of students in a space where play is encouraged obscures into a radical element and becomes graffiti mediated by a system world.

Return to the opening title—“Public Marginalia: (Re)Markable Conversations (Re)Surfacing and (Re)Buffed”—on the article and on Post-its, but the AUTHOR’s writing of it is reversed, as if being erased.

As students play in the shadows of the tunnel, they are playing with the shadows of a system world that seemingly attempts to keep them from playing where play is kairotically welcome and fostered, where students are fighting for a place where their voices can be in place. The system world itself, though, has interjected its own voice, its own anti-discourse by taking a beloved quote out of context, out of its own place. The system has turned its own voice into a scream that students have heard and have reclaimed and remarked upon with the discursive power which knowledge gives.

Works Cited

- Baudrillard, Jean. Symbolic Exchange and Death. Sage, 1978.

- Brooke, Robert. “Underlife and Writing Instruction.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 38, no. 2, May 1987, pp. 141-53.

- Cintron, Ralph. Angels’ Town: Chero Ways, Gang Life, and Rhetorics of the Everyday. Beacon P, 1997.

- Cresswell, Tim. “The Crucial ‘Where’ of Graffiti: A Geographical Analysis of Reactions to Graffiti in New York.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 10, no. 3, 1992, pp. 329-44.

- Ferrell, Jeff. “Freight Train Graffiti: Subculture, Crime, Dislocation.” Justice Quarterly, vol. 15, no. 4, 1998, pp. 587-608.

- Gross, Stephanie. “Madison Society Pushes for New Tradition, Paints Forbes Tunnel.” The Breeze, 14 Oct. 2013, www.breezejmu.org/news/madison-society-pushes-for-new-tradition-paints-forbes-tunnel/article_219b8fd8-346c-11e3-a567-001a4bcf6878.html.

- Jackson, H.J. “Writing in Books and Other Marginal Activities.” University of Toronto Quarterly, vol. 62, no. 2, Winter 1992-93, pp. 217-31.

- Leavins, Peter A. “Coping with Graffiti.” Letter. New York Times, 30 June 1975, p. 28.

- Macdonald, Nancy. The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity, and Identity in London and New York. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

- Madison, James. The Writings of James Madison, Volume IX, 1819-1836. Edited by Gaillard Hunt, GP Putnam’s Sons, 1910.

- Molloy, Cathryn. “‘Curiosity Won’t Kill Your Cat’: A Meditation on Bathroom Graffiti as Underlife Public Writing.” Writing on the Edge, vol. 24, no. 1, Fall 2013, pp. 17-24.

- Prial, Frank J. “Subway Graffiti Here Called Epidemic.” New York Times, 11 Feb. 1972, pp. 39, 75.

- Scheibel, Dean. “Graffiti and ‘Film School’ Culture: Displaying Alienation.” Communication Monographs, vol. 61, no. 1, 1994, pp. 1-18.

- Schjeldahl, Peter. “Graffiti Goes Legit—But the ‘Show-Off Ebullience’ Remains.” New York Times, 16 Sept. 1973, p. 147.

- Schumach, Murray. “At $10-Million, City Calls It a Losing Graffiti Fight: Lindsay, Decrying ‘Vandalism,’ Reports $24 Million a Year Would Be Needed to Reduce Defacement Appreciably Beautification Suggested.” New York Times, 28 Mar. 1973, p. 51.

- “‘Taki 183’ Spawns Pen Pals.” New York Times, 21 July 1971, p. 37.

Music

- EUS. “El Camino.” Tras El Horizonte, ccCommunity, 16 May 2011. FreeMusicArchive.org, CC Attribution Noncommercial-No Derivatives 3.0.

- Mitoma. “Formless.” Formless: EP, Section 27, 23 Aug. 2015. FreeMusicArchive.org, CC Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0.

- Podington Bear. “Rarified.” Yearning, Music for Video, 11 Mar. 2014. FreeMusicArchive.org, CC Attribution Noncommercial 3.0.

Additional voice-overs provided by

- Cecille Deason

- Cathryn Molloy

Additional photos provided by

- Rachael Linthicum

Additional thanks to

- Juliana Garabedian

- Kevin Jefferson

- Dave Stoops

- The Center for Instructional Technology, JMU

- The Center for Faculty Innovation, JMU

- Traci Zimmerman

- Students who have shared stories and images over the years

Cover Image Credit: AUTHOR

Keywords: graffiti, transgressive, marginalia, counter-public, multimodal

Scott Lunsford is associate professor of Writing, Rhetoric & Technical Communication at James Madison University. His research focuses on the intersections of multimodality, genre, mobility, and embodied knowledge and rhetoric. Through methods of sonic and video research and production, he explores graffiti and other counter-rhetorics in transgressive spaces. He has published in the RSA 2016 Proceedings, Present Tense, Writing on the Edge, Rhetoric Review, and Studies in Popular Culture. Biography photo by Nytzia Deason

Scott Lunsford is associate professor of Writing, Rhetoric & Technical Communication at James Madison University. His research focuses on the intersections of multimodality, genre, mobility, and embodied knowledge and rhetoric. Through methods of sonic and video research and production, he explores graffiti and other counter-rhetorics in transgressive spaces. He has published in the RSA 2016 Proceedings, Present Tense, Writing on the Edge, Rhetoric Review, and Studies in Popular Culture. Biography photo by Nytzia Deason