How To Be Gay with Locative Media: The Rhetorical Work of Grindr as a Platform

In 2015, the mobile gay male dating and hookup app Grindr began a shift in its marketing, technological infrastructure, and interface: While the app remained a “gay dating app” in much of its marketing and uses, it also become a “platform” in an attempt to generate revenue through advertisers and partnerships and to broaden the app’s usefulness for users. Since its launch in 2009, Grindr’s goal had been to help men find other men for sex, dates, or chatting nearby. Using geolocation, profiles are mapped onto a cascading grid so that a user can see and message the 100 profiles closest to him (or 600 profiles, if a user subscribes to the premium version, Grindr XTRA). Grindr thus acts as locative media (also called location-based technologies or geospatial media) that draws on the GPS capabilities of mobile devices in ways that allow users to interact with (and thus change their experiences of) their physical environments. As Adriana de Souza e Silva argues, locative media create hybrid spaces where physical and digital spaces are merged or blurred, allowing for “new way[s] of moving through a city and interacting with other users” (262; see also de Souza e Silva and Sutko; de Souza e Silva and Frith; Farman). In effect, Grindr remaps everyday heterosexual spaces into queer spaces, “cultivating innovative, non-normative intimate cultures through which gay men experience feelings of community and belonging, in the form of friendships, sexual liaisons or romantic relationships” (Batiste 114). However, Grindr’s transformation in its infrastructure, marketing, and interface has led to changes in the mobile app, transforming it from simply a dating or hookup app into a platform that also helps to construct users’ identities. In a 2015 Daily Beast interview about Grindr’s attempt to become “more than a dating app,” Grindr founder and CEO Joel Simkhai explained that the initial goal of Grindr had been “to solve gay men’s problems” by helping them find “Who’s around me,” but now Grindr was developing new, broader goals: By becoming a platform, Grindr sought to become, in the words of reporter Ben Collins, more of “a much larger lifestyle brand” (Collins).

Grindr’s shift to a “platform” is important both materially and discursively in its reconstitution. I understand platform as material “digital infrastructure that enable two or more groups to interact” (Srnicek 43) and as a discursive concept used to shape rhetoric about digital spaces and to shape practices in those spaces. In my understanding of how platforms shape experiences online, I follow Tarleton Gillespie, who in “The Politics of ‘Platforms’” explains how YouTube articulates itself as a platform so that the site can appeal to advertisers, professional content producers, policymakers, and users alike. Through its platform rhetoric, YouTube draws on disparate and potentially conflicting meanings of the concept—a computational platform that can be built upon, a political platform to speak from, an architectural platform to build on, and so forth (349-352)—to then promote itself as “a progressive and egalitarian” site for self-expression (350) and court advertisers and media producers (355). Gillespie argues that through this platform rhetoric, YouTube helps to “[shape] the contours of public discourse online” (358). This shaping is accomplished in part through eliding the tensions among the various meanings of platform. For example, YouTube can tout itself as an egalitarian political platform where users can express themselves while also indexing content in ways that make some videos (like those deemed sexually suggestive) more difficult to find and providing access to media conglomerates to take down content they see as violating copyright (357-359).

In this article, I build on Gillespie’s argument that platform rhetoric shapes public discourse by showing how it also shapes identity: The term “platform” helps to reconstitute Grindr’s marketing and infrastructure in ways that contribute to the reconstitution of users and to resituate the app within a homonormative affective economy. By homonormative I draw on the work of queer theorists like Lisa Duggan and Jasbir Puar who have critiqued normalizing sexual politics and rhetoric. As Duggan explains, homonormativity “is a politics that does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions, but upholds and sustains them, while promising the possibility of a demobilized gay constituency and a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption” (50). Homonormativity works through logics that privatizes citizenship as homo eoconomicus, integrates white gays and lesbians into nationalism, and constructs urban, white gay sensibilities as modern through pathologizing racial, rural, and lower-class others (Halberstam 36-37; Puar).

As Anne Frances Wysocki and Julia Jasken explain, interface design is “also the design of users,” and although that design of users is not totalizing or deterministic—in part “because the contexts in which we use software are so large and unfixed”—interfaces do help to shape subjectivity, identity, and social practices (35). Rhetoric scholars like Wysocki and Jasken, Ian Bogost, and Collin Gifford Brooke encourage scholars to not simply attend to the visual aspects of interfaces, but also to the software and code that creates those visual interfaces (Bogost 24-28; Brooke 48; Wysocki and Jaskin 45). Thus, I attend to both Grindr’s discursive construction as a platform and its computational infrastructure as a platform. Following Anne Helmond, platforms as computational infrastructure do work (2), changing the architecture of sites and apps so that they have two interfaces: “a user interface for human consumption . . . and a software interface for machine consumption,” through Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) (4). Importantly for my brief analysis here, Grindr’s redesign and rhetoric of “platform” do affective work to help to constitute and reaffirm certain types of gay identity. Through both the rhetorical and architectural shifts Grindr deploys, it allows the app to move from a site that “connects men, haphazardly, deliriously” (Corey and Nakayama 21) to one that more closely aligns with homonormative discourses and the so-called pink market.

In order to explore the rhetoric of platforms as it plays out with Grindr, I draw loosely on the heuristic Brooke develops in Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media. Brooke proposes that, rather than analyze “(textual) objects” in digital environments, we instead think “more in terms of (medial) ecologies” and interfaces (23). He proposes a “light structure” (52) for analyzing new media that attends to ecologies of code, practice, and culture (47). I use Brooke’s heuristic to organize my argument: I attend first to Grindr’s platform code, explaining infrastructural changes in the app as it transitioned to a platform. I then turn to practices made possible by these changes in code on Grindr. In particular, I focus on how changes in infrastructure allow for changes in practices regarding advertisements that help to develop and reinforce what Katherine Sender identifies as a “gay sensibility” (“Gay Readers” 75). These advertisements—in conjunction with rhetorics of equality and inclusion promoted by the platform that are in tension with the platform’s laissez faire attitude toward exclusionary profile language—reinforce a normative gay sensibility that idealizes toned, white, youthful, and masculine bodies. Much like the tensions elided in YouTube’s platform rhetoric that Gillespie critiques, Grindr’s platform rhetoric elides a tension between its explicitly progressive political rhetoric and the practices on the app that can make it unwelcoming to nonnormative users and that privilege normative beauty standards. In the conclusion, I discuss the homonormative culture that Grindr participates in with its platform rhetoric, situating the app within larger cultural forces of homonormative gay sensibilities. In effect, Grindr’s platform rhetoric helps it to participate in a broader cultural pedagogy of “how to be gay,” to draw on the title of David Halperin’s well-known book on gay aesthetics and subjectivity.

Grindr’s New Platform Infrastructure

Since its launch in the Apple App Store in 2009, Grindr has been a huge success: As of mid-2017, it boasts 3 million daily active users worldwide who average 54 minutes on the app daily and send a collective 228 million messages and 20 million photos to each other daily (“Fact Sheet”). However, Grindr’s efficiency as an app and development as a company was limited by the programming infrastructure that had been developed over the years. The app had been written on Ruby on Rails, its geolocation algorithms were locally developed, and the chat feature was built in-house using Jabber, the open source extensible messaging and presence protocol. In effect, Grindr was an assemblage of a “bunch of different custom technologies that the team built from scratch” (Jackson). The result of all of this local coding was that developers were constantly re-writing code (at large costs), the app was difficult to scale for a growing user base, the company couldn’t update the app regularly, and users would experience outages during moments of high-volume traffic. Thus, the company saw a need to turn to a platform mentality and infrastructure. In 2015, the company partnered with a variety of services to create a “stack,” or a collection of programming elements, comprised of third-party services like Amazon Web Services and Erlang Solutions’ MongooseIM (an instant messaging platform). The effect of this change was the move from an app programmed in an expensive and ad hoc manner to a platform programmed for efficiency, scalability, and flexibility (Jackson; “What Is GrindrLabs?”).

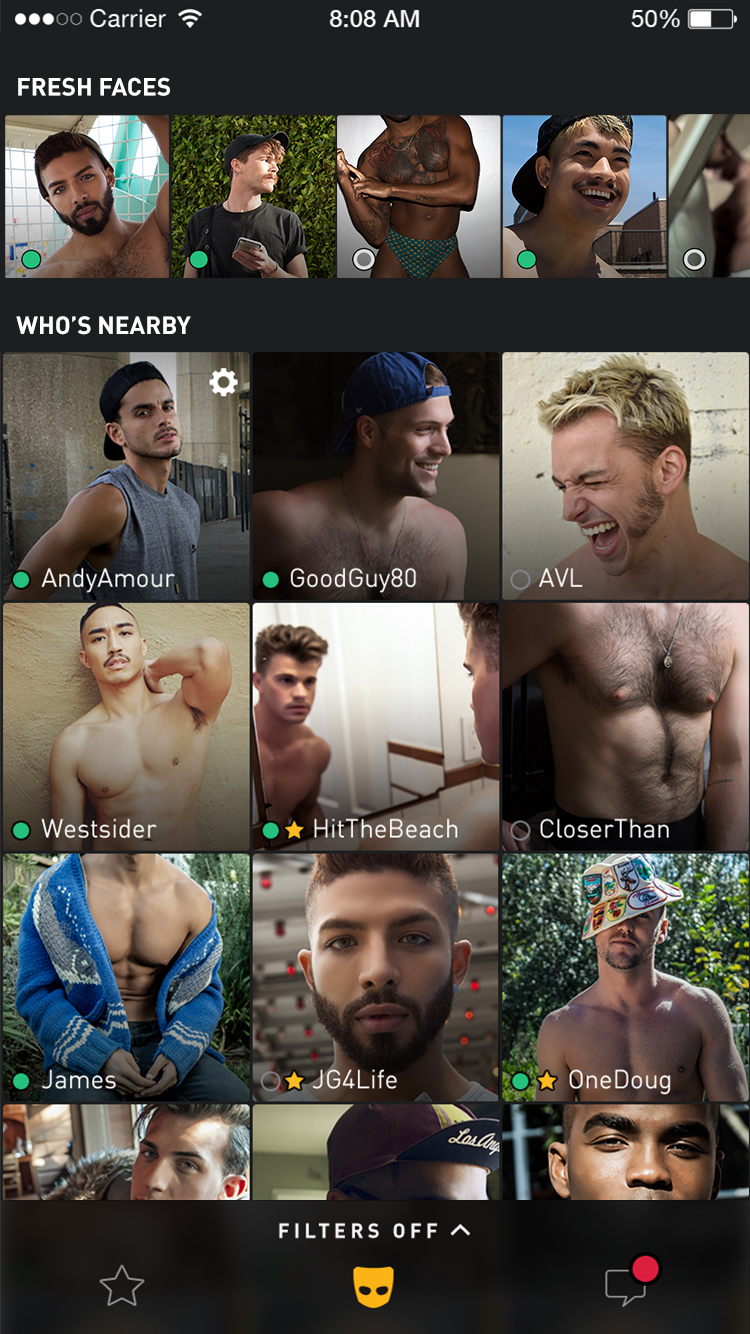

With this new platform mentality, GrindrLabs (Grindr’s agile coding shop) redesigned the infrastructure to work with a variety of already-existing cloud computing and caching services. While these changes were likely not observed by a typical Grindr user (except that Grindr had fewer outages and released a new interface design in 2016, pictured in figure 1 above), this infrastructural change would allow Grindr to scale up from simply a dating app to a platform that assists in the shaping of users’ identities. In effect, Grindr joined the many other tech companies that base their business model on platforms (see Srnicek). As Brooke observes, discursive practices in an interface depend on an ecology of code, or “all those resources for the production of interfaces more broadly construed, including visual, aural, spatial, and textual elements, as well as programming codes” (48). Thus, Grindr’s discursive platform rhetoric is dependent upon its platform code: a computational platform or infrastructure “that bring[s] together different users, customers, advertisers, and even physical objects” (Srnicek 43; see also Gillespie 349). Grindr’s shift to a platform ecology allows it to bring together users and advertisers in different ways than it had before this infrastructural change.

Practices on Grindr: Advertisements, Politics, and Exclusions

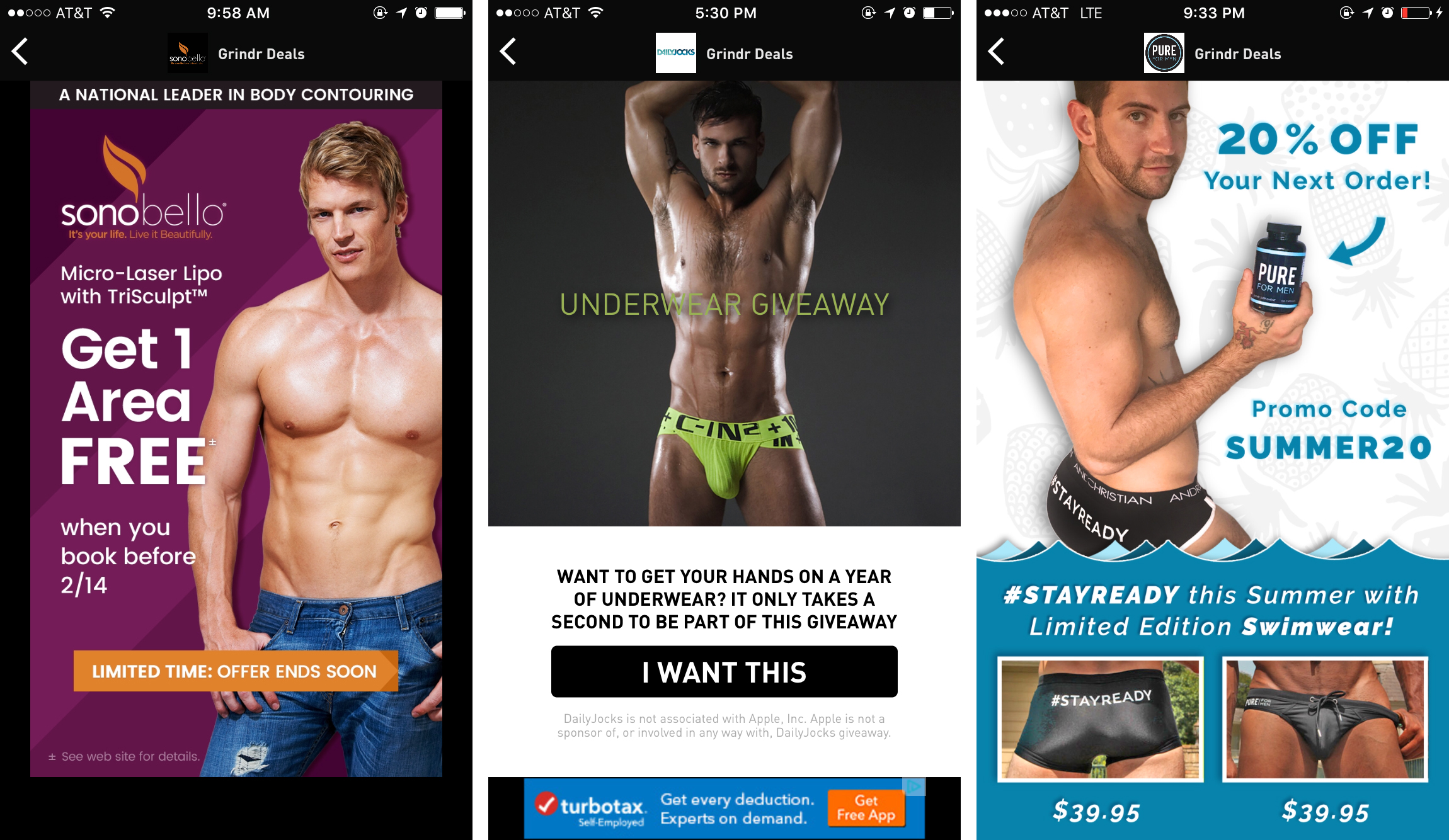

Before Grindr’s rollout of their new interface in 2016, advertisements were minimally invasive. Most were located on a small bar at the bottom of the screen and seemed to be relatively undirected: a random ad for a game, TurboTax, or an underwear website. As a user, I only tapped on these ads accidentally, when my thumb would inadvertently hit the ad as I fumbled with my iPhone. But with the new chat infrastructure in place, Grindr’s new design allowed for visual ads to be sent from “Grindr Deals” through chat messages, such as the three ads pictured below.

These ads are more clearly geared toward a normative gay male market than the small, non-intrusive ads that had populated previous iterations of the app. And because they are delivered through the chat interface, I speculate that they are much more likely to be clicked on and viewed than previous, less intrusive ads. (I have clicked on every advertisement delivered through Grindr Deals, just to keep my chat cleared, and have purchased a few of the advertised products as well, whereas I had never purchased something advertised on Grindr before the introduction of Grindr Deals.) Whereas ads for video or mobile games are not necessarily a part of a gay economy, fashion underwear, laser liposuction, and fiber pills marketed explicitly for gay men circulate within a gay market. These commodities depend on and help construct a market of gay consumerism, which Sender identifies as establishing a “gay sensibility” (“Gay Readers” 75) that focuses on consumerism at the expense of politics and typically promotes the ideals of a toned, white, youthful, and masculine body (93-95). And clearly, these ads are marketed toward the fairly affluent: laser liposuction is costly, gay-marketed underwear like C-IN2 is more costly than a 3-pack of Hanes, and Pure fiber pills (advertised to keep one’s gastrointestinal tract ready for anal sex) are more expensive than ones purchased at a pharmacy. As Sender argues, the gay market helps to construct gay identities, which are formed in part through being addressed (Business 5). Sender argues further that the gay market produces a difference: gays and lesbians are constructed as different from heterosexual consumers. But this is a still a very limited difference, as gay marketing “promotes particular kinds of distinctions . . . marked by privilege and good taste” (Business 236). Particularly, this gay sensibility is racialized, gendered, and classed, as gay marketing tends to homogenize gay identities, ignoring racial, gender, and class differences and focusing on thin and/or muscular, affluent white gay men (154-163).

The three ads shown above are not alone in idealizing thin, masculine, white gay physiques. Of the dozens of advertisements I took screenshots of for this project, nearly each one that featured images of men included an attractive young man. (One exception featured a drag queen advertising Pure fiber pills for Valentines Day. Another ad for laser liposuction featured a man in his 40s or 50s with graying hair and a beard; the accompanying copy read, “Daddy wanting to look a little less ‘Daddy’?”) All these men appeared to be white or could pass as white, and if the image included their torsos, they were generally shirtless with well-defined pecs and abs. These ads—whether for fiber pills, fashion underwear, liposuction, home-STI testing, clothing, or wine—encourage users to identify with and idealize white, able-bodied, toned men, promoting an affluent, white, masculine ideal. Many of these ads seem to function in ways similar to the Abercrombie & Fitch marketing and advertising that Dwight McBride critiques for “celebrat[ing] whiteness—a particular privileged and leisure-class whiteness” (66)

As a user and critic of Grindr, I can’t be certain how many users see these kinds of ads (which I monitored and took screenshots of during the first half of 2017). While Grindr’s practices for targeting ads is somewhat opaque, the company and their third-party partners (like Google Analytics) do collect data on geolocation, device type, profile information, demographic information, and information from third-party platforms like Facebook or Twitter that users might connect to their Grindr profile (“Grindr Privacy Policy”). Grindr has made a concerted effort to increase ad revenue: Whereas 75 percent of the company’s income in 2012 was based on users’ subscriptions to Grindr Xtra, which offers more advanced features like push notifications and unlimited blocks (Hall), Grindr began a campaign in 2014 to bring in more ad revenue as “a potentially lucrative future data business” (O’Reilly). This campaign resulted in a reported 65 percent increase in ad revenue in 2015 (Johnson) by targeting ads using data from users and promoting those users as affluent, ideal consumers. Grindr’s 2014 media kit promoted their “highly engaged audience” of “gay affluent, tech-savvy men,” noting that gay men in the United States typically earn more income than the average American and spend more money “on products and services than their straight counterparts” (“Grindr Advertising” 1). In one successful ad campaign, the gym chain Crunch Fitness targeted ads on Grindr to men located in New York who frequented gyms, seeing a successful promotion of their trial membership that led to plans to expand advertisements to other cities (Johnson).

What distinguishes Grindr’s gay marketing from most of the examples Sender discusses in Business, Not Politics is that Grindr’s platform rhetoric is explicitly political. Sender explains that many companies justify their gay market advertisements by arguing that it is good business, not a political statement (2). However, Grindr has developed explicitly political rhetoric in conjunction with its platform rhetoric. Intermixed with advertisements from Grindr Deals are promotions for its “Grindr for Equality” campaign, which attempts to “mobilize, inform, and empower . . . users” in campaigns “to promote justice, health, safety, and more for LGBTQ individuals” (“Grindr 4 Equality”). These messages have promoted voter initiatives, education about refugees, HIV testing, information about violence against gays in Chechnya, and petitions to support net neutrality or oppose anti-queer or anti-trans legislation or presidential policy.

However, Grindr’s focus on political equality comes into tension with its laissez faire approach to user practices. While Grindr’s “Profile Guidelines” tell users to not post racist or bigoted material “that might offend our community” (“Profile Guidelines”), the term offend is of course subjective, and many users post racial and sexual preferences in their profiles that are exclusionary. This practice, commonly known as the “No Fats, No Femmes, No Asians” phenomenon, is ubiquitous: Users state in their profiles that they aren’t interested in a variety of other types of bodies: fat bodies, Black bodies, feminine bodies, Asian bodies, and so forth (see Miller; Pritchard 192-193; Raj; Riggs). This practice is so common and understood among users that sites like Douchebags of Grindr (http://www.douchebagsofgrindr.com/) share and comment on profiles that include such discriminatory language. This language, I argue, helps to shape the public of Grindr into a space less welcoming—even hostile—to bodies that don’t meet white, masculine ideals, performing the sort of violent “literacy normativity” that Eric Darnell Pritchard describes and critiques in Fashioning Lives: Black Queers and the Politics of Literacy. As Pritchard explains, while we shouldn’t police sexual desires, we do need to “identify and deal substantively with the ways that some of these proclivities emerge from or reinforce various forms of oppression and domination, including stating that some people have no value because they are of color, or too big, or too small, or too effeminate, or too old, or transgender, or gender-nonconforming” (198). Grindr has encouraged users to not post this exclusionary language but doesn’t remove profiles that include this language. In effect, Grindr’s platform rhetoric produces a tension: Grindr markets itself as a progressive company that seeks social justice through its Grindr for Equality campaign, but advertises to (and thus helps construct) its users as a certain type of affluent gay and has a laissez faire approach to discriminatory profile language that makes the public of Grindr less inclusive.

Conclusion: Grindr’s Participation in Homonormative Culture

Grindr’s platform rhetoric thus enabled the company to materially construct a platform at the level of code, creating a more dynamic computational infrastructure that allows the company to target ads through the app’s chat feature. These ads, as I’ve briefly argued, promote an affluent, white, masculine ideal. Additionally, while Grindr promotes progressive political positions through Grindr for Equality, the progressive stance of Grindr is undercut by its laissez faire attitude toward user practices that can make the app an exclusionary or unwelcome space for bodies that are nonwhite, gender-nonconforming, disabled, fat, or otherwise nonnormative.

Many have celebrated the potential for Grindr to eschew institutions and allow for what Samuel Delany calls contact: cross-cultural and cross-class encounters that allow for surprise and new relationalities (123-125). Frederick Corey and Thomas Nakayama suggest this potential in Grindr: “With little attention to social categories, Grindr has the potential to disrupt social institutions such as marriages, gay or straight, but offers no institution in its place other than free flowing desire” (21; see also Batiste). Elsewhere, I too have also made similar arguments, that Grindr allows for new and surprising intimacies with strangers (Faris).

I don’t believe that Grindr’s technological and rhetorical shifts to a platform negate or destroy these opportunities for new intimacies with strangers, but I do believe they contribute to a privatization of a public space and the potential closeting of queer subjectivity—one that could be open to new desires, intimacies, possibilities—through the construction of homonormative identities and practices. My contention here is that Grindr’s shift from merely an “app” to a “platform” allows it to participate in a homonormative affective economy. As Duggan explains, homonormativity seeks “a privatized, depoliticized gay culture” (50). The potentially open and accessible interface of Grindr—all one needs to use Grindr is a smart phone—becomes less inclusive, less open to difference. Sexual desires are privatized—a user’s statement that he’s not into Blacks is merely a personal preference and not seen as language that affects the inclusivity of the public—and users are encouraged to identify with products marketed toward affluent gays. The effect of this technological and discursive platform rhetoric is to make the public space of Grindr more normative, to assist in the construction of a certain type of ideal gay: affluent, able-bodied, masculine, toned, and likely white, “marked by privilege and good taste” (Sender, Business 236).

As Michael Warner has observed, queers have not had access to the same sort of institutions for culture-building that other marginalized groups have had access to, like families and churches. Instead, queer “institutions of culture building have been market-mediated: bars, discos, special services, newspapers, magazines, phone lines, resorts, urban commercial districts” (“Introduction” xvi-xvii). Grindr has the potentiality of being such a market-mediated counterpublic, where queers can meet in virtual space, encountering difference and developing new intimacies with each other, ones that play out both through the app and in physical space. As locative media, Grindr not only affords the possibility of intimate contact online, but also of remapping spaces as queer spaces where new contacts and intimacy can happen nearly anywhere. My concern in this article is that the tensions in Grindr’s platform rhetoric—between an explicitly progressive political rhetoric and a hands-off approach to users’ exclusionary language practices—and Grindr’s increased use of ads that reinforce and reproduce normative ideals of whiteness, youth, and masculinity, encourage queer men to, in Warner’s words, “increasingly understand themselves as belonging to a market niche rather than to a counterpublic” (The Trouble 147). While Grindr’s redesign and recent platform rhetoric doesn’t negate the possibility for allowing for surprise and new contacts, it does seem to help constitute more predictable, consumer-driven, normative gay identities. We might wonder how platforms could be designed—especially as their goal is to typically make money off of data—in ways that imagine and promote more ways of being (or being gay) in the world.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dustin Edwards, Bridget Gelms, and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on previous drafts of this article.

Works Cited

- Batiste, Dominique Pierre. “‘0 Feet Away’: The Queer Cartography of French Gay Men’s Geo-social Media Use.” Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, vol. 22, no. 2, 2013, pp. 111-32. doi:10.3167/ajec.2013.220207

- Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. The MIT P, 2007.

- Brooke, Collin Gifford. Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media. Hampton Press, 2009.

- Collins, Ben. “Grindr Tries To Become a Lifestyle Brand.” The Daily Beast, 22 Nov. 2015, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/11/22/grindr-tries-to-become-a-lifestyle-brand.html

- Corey, Frederick C., and Thomas K. Nakayama. “deathTEXT.” Western Journal of Communication, vol. 76, no. 1, 2012, pp. 17-23.

- de Souza e Silva, Adriana. “From Cyber to Hybrid: Mobile Technologies as Interfaces of Hybrid Spaces.” Space and Culture, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 261-78. doi:10.1177/1206331206289022

- de Souza e Silva, Adriana, and Jordan Frith. “Locative Mobile Social Networks: Mapping Communication and Location in Urban Spaces.” Mobilities, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 485-505. doi:10.1080/17450101.2010.510332

- de Souza e Silva, Adriana, and Daniel M. Sutko. “Theorizing Locative Technologies Through Philosophies of the Virtual.” Communication Theory, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 23-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01374.x

- Delany, Samuel R. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. New York U P, 1999.

- Duggan, Lisa. The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy. Beacon Press, 2003.

- “Fact Sheet 2017.” Grindr, 2017, http://www.grindr.com/press/

- Faris, Michael J. “Queering Networked Writing: A Sensory Autoethnography of Desire and Sensation on Grindr.” Re/Orienting Writing Studies: Queer Methods, Queer Projects, edited by William P. Banks, Matthew B. Cox, and Caroline Dadas, U P of Colorado and Utah State U P, forthcoming.

- Farman, Jason. Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media. Routledge, 2012.

- Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Politics of ‘Platforms.’” New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, 2010, pp. 347-64. doi:10.1177/1461444809342738

- “Grindr 4 Equality.” Grindr, 2017, https://www.grindr.com/community

- “Grindr Advertising.” Grindr, May 2014, https://s3.amazonaws.com/grindr_marketing/US+Media+Kit+05.2014.pdf

- “Grindr Privacy Policy.” Grindr, 30 March 2017, https://www.grindr.com/privacy-policy/

- Halberstam, Judith. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York U P, 2005.

- Hall, Mitchell. “Up Close and Personal: Q&A with Grindr Founder Joel Simkhai.” PCMag, 23 July 2013, https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2421919,00.asp

- Halperin, David M. How To Be Gay. Harvard U P, 2012.

- Helmond, Anne. “The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready.” Social Media + Society, vol. 1, no. 2, 2015, pp. 1-11. doi:10.1177/2056305115603080

- Jackson, Joab. “Grindr Settles into a Scalable Platform to Expand Its Range of Services.” The New Stack, 29 Feb. 2016, http://thenewstack.io/grindr-settles-scalable-platform-expand-range-services/

- Johnson, Lauren. “Brands Make a Match with Dating Apps.” Adweek, 19 May 2015, http://www.adweek.com/digital/brands-make-match-dating-apps-164805/

- McBride, Dwight A. Why I Hate Abercrombie & Fitch: Essays on Race and Sexuality. New York U P, 2005.

- Miller, Brandon. “‘Dude, Where’s Your Face?’ Self-Presentation, Self-Description, and Partner Preferences on a Social Networking Application for Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Content Analysis.” Sexuality & Culture, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 637-58.

- O’Reilly, Laura. “How Gay Hook-Up App Grindr Is Selling Itself to Major Brand Advertisers.” Business Insider, 26 Nov. 2014, http://www.businessinsider.com/grindr-ceo-joel-simkhai-on-advertising-pitch-deck-2014-11

- “Press Kit.” Grindr, 2017, https://www.grindr.com/press

- Pritchard, Eric Darnell. Fashioning Lives: Black Queers and the Politics of Literacy. Southern Illinois U P, 2017.

- “Profile Guidelines.” Grindr, 2017, https://www.grindr.com/profile-guidelines/

- Puar, Jasbir K. “Mapping US Homonormativities.” Gender, Place and Culture, vol. 13, no. 1, 2006, pp. 67-88.

- Raj, Senthorun. “Grindring Bodies: Racial and Affective Economies of Online Queer Desire.” Critical Race and Whiteness Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2011, pp. 1-12. http://www.acrawsa.org.au/files/ejournalfiles/171V7.2_3.pdf

- Riggs, Damien W. “Anti-Asian Sentiment Amongst a Sample of White Australian Men on Gaydar.” Sex Roles, vol. 68, no. 11, 2003, pp. 768-78.

- Sender, Katherine. Business, Not Politics: The Making of the Gay Market. Columbia U P, 2004.

- —. “Gay Readers, Consumers, and a Dominant Gay Habitus: 25 Years of the Advocate Magazine.” Journal of Communication, vol. 51, no. 1, 2001, pp. 73-99.

- Srnicek, Nick. Platform Capitalism. Polity, 2017.

- Warner, Michael. “Introduction.” Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory, edited by Michael Warner, U of Minnesota P, 1993, pp. vii-xxxi.

- —. The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life. Harvard U P, 1999.

- “What Is GrindrLabs?” Grindr, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20170108230032/http://www.grindr.com/labs/

- Wysocki, Anne Frances, and Julia I. Jasken. “What Should Be an Unforgettable Face. . . .” Computers and Composition, vol. 21, no. 1, 2004, pp. 29-48. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2003.08.004

Cover Image Credit: George, Terry. “EDITE67A3591.” Flickr, 10 Apr. 2015, https://flic.kr/p/rwPoAw

Michael J. Faris is an assistant professor in technical communication and rhetoric in the English Department at Texas Tech University. His research interests include new media rhetorics, digital literacy practices, and the intersections of queer theory and rhetorical theory. He published

Michael J. Faris is an assistant professor in technical communication and rhetoric in the English Department at Texas Tech University. His research interests include new media rhetorics, digital literacy practices, and the intersections of queer theory and rhetorical theory. He published