That Camera Won’t Save You! The Spectacular Consumption of Police Violence

James Carey once wrote that in the late 19th century people celebrated “electronic technology as the motive force of desired social change” (88). But he continued by noting that electronic communication technologies actually furthered inequality rather than lessened it. Lisa Nakamura makes a similar assessment about the Internet, arguing that some people have declared the Internet “a ‘utopia’ where ‘there is no race, there is no gender’” (Digitizing Race 337). Nakamura challenges this view, however, nothing that anyone who thinks racism is a thing of the past “need only look to the Internet for proof that this is not so” (“Gender and Race Online” 81). When Carey and Nakamura wrote about these two celebrations of technology, they speak to, but did not explicitly have in mind, the contemporary celebration of body cameras as preventative of police brutality. In light of the recent police murders of Black adults, and children, like Michael Brown, Tanisha Anderson, Tamir Rice, and Miriam Carey, body cameras are championed by politicians, the NAACP, and reporters as necessary to police the police.

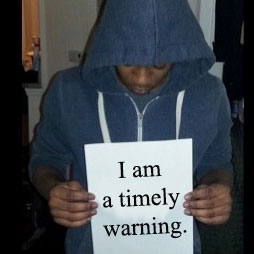

Taking a page from Carey and Nakamura, I am skeptical of the antiracist, radical potentiality of body cameras. I agree with Ben Wetherbee’s argument that “rhetorical criticism benefits from accounting for memes,” but I want to push this position into a discussion of rhetoric, mimicry, and black studies. I am concerned with the reduction of antiblack violence to Internet mimicry. I apply Eric Watt’s “spectacular consumption” to Barry Brummett’s “representational anecdote” to argue that body cameras (but also cell phone videos and social media) further normalize the commodification of black death. The capability to turn images of Black people recently murdered or beaten by police into Internet memes further normalizes antiblack violence as spectacle, throwing doubt on the radical potential of body cameras.1 While police brutality has intensified important social movements like #BlackLivesMatter and #SayHerName, I focus my critique on unquestioned celebrations of body cameras.

The exigence of police brutality guides two related anecdotes about body cameras I critique in the proceeding section: one assumes body cameras protect citizens; the other assumes they protect police. Yet, criticism of cameras as preventive of police violence is not new. Some point to Rodney King’s 1991 beating by four White police officers, all acquitted despite video evidence.2 I conclude by aligning myself with this position and extending it: body cameras are not preventative of police brutality but may go a step further to create new venues to spectacularly consume antiblack violence.

Spectacular Anecdotes

Following Kenneth Burke, Brummett’s representational anecdote is “a method that represents well what happens in the media because the media are anecdotal” (480). Brummett contends that media are anecdotal because they create stories that do not merely depict a problem but suggest ways to remedy it as well. Reports on police violence follow a similar pattern in popular media: police brutality is reportedly lessened by body cameras. The problem and solution to police violence is provided in media narratives. Likewise, Watts contends that not only are media far from neutral, but they exist within systems that perpetuate racism and are bound to the logics of such systems. For example, he argues television perpetuates what he calls spectacular consumption, meaning television further normalizes Black people as objects for White viewers. One example Watts and Mark Orbe use involves the three Black “Wassup?!” friends from the Budweiser commercials of the late 1990s and early 2000s. These commercials became popular for depicting three Black men greeting each other over the telephone with a long, drawn out “wuzzzzuuuppp!” Watts and Orbe note this image is viewed as ordinary in its narrative of male bonding, yet exoticized by many White male consumers as cool, hip, and “true.” Dangerously, in the assumed universality of masculine bonding, there is a covering up of the ways blackness remains as absolute Other, particularly as the three friends become a commodified image of black authenticity. Spectacular consumption also provides a framework to examine the normality of watching police violence on the nightly news, Twitter, or Facebook feeds. The media’s promotion of the problem and solution (Brummett) opens a space to view, examine, and normalize something that should be abnormal (Watts): watching people die.

In its campaign to lessen police brutality, the White House has gotten in on the celebration of body cameras. The Obama Administration proposes a three-year, $263 million investment package that makes body cameras part of a police officer’s uniform. Further, at some point body cameras will reportedly make everything “easier,” as images recorded by officers will be immediately stored in accessible digital databases. It is estimated that “the proposed $75 million investment over three years could help purchase 50,000 body worn cameras” throughout the country.3 The Obama Administration are not the only ones concerned with cameras and policing. The NAACP has called for the use of cell phone videos to prevent police brutality.4 Cameras are popularly championed as “weapons” against police brutality or “weapons” for police protection, that are, as Chris Matyszczyk reports, “Not deadly, but often deadly accurate.” Matyszczyk’s argument mirrors two related anecdotes promoted in the popular press that raise red flags about the antiracist potential of body cameras: first, body cameras protect citizens; second, body cameras protect police.

First, body cameras are celebrated as protective of citizens. Journalist Gregory Hladky states “Advocates say that police are less likely to use force improperly if they know their actions are being recorded by digital cameras” (A1). In a similar vein, reporter Vincent Fort searches for something “positive” that can come out of the death of Michael Brown, a Black teenager who was shot and killed in Ferguson, MO by former police officer Darren Wilson. For Fort, the most positive outcome for Brown’s death is an increase in police technology: “it is easy to agree with the call by Michael Brown’s parents for the use of body cameras by police as a positive outcome of the tragic death of their son” (14A). Relatedly, Tony Perry reports that in San Diego, a new city report found that body cameras have led to “less use of force by officers” (2). In St. Louis, which has seen a large share of the country’s recent protests, County Executive Steve Ehlmann tells one reporter that body cameras will be available for “‘a victim to show they really are a victim’ of police mistreatment” (Schlinkmann A9). From the Pittsburgh, PA to Denver, CO (Mitchell 4A), to Spokane, WA (Alexander 5), the body camera is championed as being on the side of citizens.

There is a related assumption that body cameras are also for police protection. The recent “Blue Alert” bill signed by President Obama furthers this discourse on police protection. The bill sets up systems modeled on “Amber Alerts for abducted children and Silver Alerts for missing seniors”5 in order to allow police officers to “be warned about new threats to law enforcement.”6 Gregory Korte reports President Obama praised the bill as a “bipartisan force,” one “so uncontroversial that it passed both the House and the Senate by voice vote.” Body cameras are also advocated for allowing better policing of suspects. Vincent Fort reports that body cameras will decrease the potential of “false reports,” where a criminal claims abuse by a police officer that did not occur (14A). Reiterating Fort’s argument, Darla Slipke reports that “If there is an issue with someone from the public claiming an officer did something or didn’t do something, it’s easy to go back and look at the video” (11). Tampa Police Chief Jane Castor states, “I believe the cameras will improve behavior of officers a little and the citizens a whole lot… It will be a whole new reality show for the community. Most people have no idea what officers deal with” (Fox 4). More so than monitoring police, viewing suspects from an officer’s perspective is necessary for Castor. Body cameras mirror reality television and ultimately soften viewers to the problems police face.

While there is no shortage of arguments that body cameras lessen violence, there are fewer statements about the recording of violence that body cameras make possible. The spectacular consumption of blackness is protected in the anecdotes that body cameras help citizens and police. On the one hand, body cameras are supposedly designed to lessen police violence. However, this should be questioned when it comes to a system of policing that begins with racism. There have been studies that reveal the roots of the police state in slave catching.7 This is why Judith Butler notes the police are structurally “placed to protect whiteness against violence, where violence is the imminent action of that black male body” (18). Black people do not have to commit acts of violence. Instead, it is violent just for Black people to even think about violence (or even self-preservation). The question quickly becomes: Who are the “citizens” protected by the body camera? The Black victim or the White person who is “safer” with one less Black person on the street? Therefore, the presumably rare moments where police kill Black people are often positioned as the fault of the victim, caused by said victim’s abnormal actions, which we can all see. As this anecdote suggests, the police murder someone like Eric Garner for selling “loosey” cigarettes, and had he just “laid down” he would still be alive. Rather than the fault of systematic, aggressive policing, Black people’s abnormality instigates police violence.

On the other hand, and relatedly, the body camera becomes an extension of a television show like Cops, providing audiences with footage of black abnormality and justifications of death. The police officer can pick a moment in a video to say they feel “threatened” in ways dead Black victims cannot. The anecdote that body cameras protect police assumes the actual threat is not police violence but Black suspects. The celebration of the body camera assumes a necessity of increased surveillance on Black people. Also it positions police as preventing criminals from becoming criminals. Video recording or not, police can justify their violence based on the act that a suspect was preparing to do—one is guilty until the camera proves them innocent, and sometimes guilty even after the camera proves them innocent (Eric Garner, for example). This anecdote facilitates a racialized tautology, where the suspect is a criminal, whether or not a crime is committed. The suspect always deserves to be harassed and monitored to protect the police.

Consuming Protective Black Mothers

The rising acceptance of cameras for antiracist struggles has been criticized from the start. Janet Vertesi, a sociologist at Princeton, warns that in her “15 years of studying how experts work with images, it has become clear that evidence never ‘speaks for itself.’” The recorded beating of Rodney King, for example, was not enough evidence to find guilty the four White police officers involved in the incident. In fact, Butler notes that the jury felt the video was evidence that King was the one in control during the beating: “The video was used as ‘evidence’ to support the claim that the frozen black male body on the ground receiving the blows was himself producing those blows, about to produce them, was himself the imminent threat of a blow and, therefore, was himself responsible for the blows he received” (18-19). Here, the police are not violent, but King is inherently violent, so violent that he incites the blows against himself. While King’s abuse sparked the LA Rebellion, the video was also used as evidence that King was to blame for what happened to him.

Not only do I agree with Vertesi when she states, “camera evidence does not an indictment make,” but also videos can now be repackaged to further normalize the abnormality of antiblack violence. The celebration of body cameras that runs through articles and White House policies promotes the consumption of antiblack violence. This is the heart of spectacular consumption where, “By encouraging viewers to ‘celebrate’ blackness conceived in terms of sameness” attention can be deflected away “from the ways in which blackness as otherness is annexed and appropriated as commodity” (Watts and Orbe 3). The proliferation of videos creates an environment where violence against black bodies is celebrated as normal. Moreover, this violence is sellable. Like Amy Wood critiques of the lynching souvenir (often body parts cut from a dead or living victim), video stands as another black object produced and consumed by (White) users. One recent example sticks out. In light of police severing the spine of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, protests erupted in April. During one protest, Toya Graham was caught on camera hitting her son, Michael Singleton. Graham recognized her son prior to the rebellion and physically halted his participation with slaps to his head.

I do not seek to criticize or celebrate Graham’s actions. I also am not equating Graham hitting her son with police murders. Instead, more interesting is the popular enjoyment of watching and sharing a Black mother beat her Black son. Since this incident, Graham and her son have appeared on CBS and ABC. Mark Wilstein reports that Oprah Winfrey has celebrated Graham. Kyle Smith of the New York Post, long known as a conservative newspaper, touts Graham as the “mother of the year.” Unlike the other presumably absent mothers (and fathers) in mid-April, a Black, single mother is normalized as a “great mother” by Smith only because she slaps her son on camera for White viewers to see. A quick YouTube search of “Toya Graham” also shows that the video of Graham hitting Singleton, during the initial writing of this article, had 88,292 views after one week. While this video was not recorded by police body cameras, it does speak to a compulsive need for audiences to see, celebrate, and consume violence against black bodies. As YouTube views continue to climb, users engage in, and recreate, processes that situate violence against black bodies as entertaining and normal. Here, a camera does not halt antiblack violence but further commodifies it.

Body cameras are also vehicles for profiting off antiblack violence. In addition to worrying about the visibility of such violence, we should be concerned that it makes wealthy Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter. With the meme-ification of Eric Garner’s death (he and Michael Brown have their own KnowYourMeme.com pages), each “like” and “view” increases advertising dollars. By and large an ignored component of these memes, remixed from body cameras and cell phone videos, is how they are profitable for White people, whether designed to be humorous or promote awareness. The repeatable image of a Black mother slapping her son, or a White police officer shooting a Black driver for a missing license plate, increases the bottom line of an elite few. In light of potential recordings and remixings of antiblack violence, the assumption that cameras transform societal ills is difficult to swallow. Instead, body cameras provide new means to see, analyze, remake, and profit off the black body.

The mix of video clips below provides a quick glimpse of how body cameras and cell phone videos are used to normalize forms of antiblack violence. As this argument is against depicting images of antiblack violence, only brief clips are selected in order to show the media circus that structures the current discussion of police violence. (Video coedited by the author and Alex Ingersoll)

Endnotes

- This article begins with an argument that memes and remixes of black death should not be looked at. Therefore, I do not think it makes sense to post an image of a meme showing the deaths of people like Michael Brown or Eric Garner. If the reader is so inclined to see images like this, I suggest you examine the KnowYourMeme.com databases for Eric Garner and Michael Brown. return

- Janet Vertesi critiques the idea that body cameras will prevent police mistreatment. Vertesi points to Rodney King’s brutal beating as proof that more video footage will not end racism. return

- See the White House’s official statement, “Fact Sheet: Strengthening Community Policing.” return

- A recent CNN article shows that the NAACP is actively calling on people to use cell phones as weapons in the fight against racist police brutality. return

- See Gregory Korte’s “Obama Signs ‘Blue Alert’ Law to Protect Police.” return

- See David Li’s “Obama Signs Bill Named for Slain NYPD Cops.” return

- Christian Parenti and Anthony Perez, et. al. both lay out the history of policing in the US, which connects back to slave catchers. After US slavery, slave catchers parlayed their positions (particularly as being skilled at hunting people down) into the creation of the contemporary police forces. return

Works Cited

- “#SayHerName: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women.” #SayHerName, n.d. Web. 13 June 2015. http://www.aapf.org/sayhernamereport.

- Alexander, Rachel. “Police Body Camera Pilot Ends. Spokesman Review 31 December 2014: 5. Print.

- “All #BlackLivesMatter. This is Not a Moment, but a Movement.” #BlackLivesMatter, n.d. Web. 13 June 2015. http://blacklivesmatter.com/about/.

- “An Animated Reenactment of both Stories in the Mike Brown Shooting!” World Star Hip Hop, 27 Nov. 2014. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. http://www.worldstarhiphop.com/videos/video.php?v=wshh4Siv6UdfC04rlKOy.

- “Baltimore Riots Mom Toya Graham — Oprah Gave Me Thumbs Up for Smackdown on My Son.” TMZ, n.d. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. http://www.tmz.com/videos/0_mk92wqfe/.

- “Body Camera: Man Pulls BB Gun on Cops.” CNN, 6 July 2015. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. http://www.cnn.com/videos/justice/2015/07/07/texas-police-bb-gun-shootout-dnt.kltv/video/playlists/caught-on-bodycam/.

- “Body Cam Video from Sam DuBose Shooting Released.” CNN, 29 July 2015. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. http://www.cnn.com/videos/us/2015/07/29/university-of-cincinnati-police-officer-body-cam-shooting-vo.cnn/video/playlists/cincinnati-traffic-stop-shooting-sam-dubose/.

- Brummett, Barry. “Burke’s Representative Anecdote as a Method in Media Criticism.” Contemporary Rhetorical Theory: A Reader. Ed. John Louis Lucaites, Celeste Michelle Condit, and Sally Caudill. New York: The Guilford Press, 1999. 479-93. Print.

- Butler, Judith. “Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia.” Reading Rodney King, Reading Urban Uprising. Ed. Robert Gooding-Williams. New York: Routledge, 1993. 16-22. Print.

- Carey, James. Communication as Culture. New York: Routledge, 2009. Print.

- “Eric Garner’s Death – Years of Experience.” Know Your Meme, n.d. Web. 13 June

http://knowyourmeme.com/photos/797897-eric-garners-death. - “Fact Sheet: Strengthening Community Policing.” The White House, n.d. Web. 7 May

https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/12/01/fact-sheet-strengthening-community-policing. - Fort, Vincent. “Cameras Protect, Police, Public.” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution 1 January 2015: 14A. Print.

- Fox, Geoff. “Chief, Sheriff Tout Benefits of Body Cameras; Law Enforcement Leaders Speak at Saint Leo.” The Tampa Tribune 17 April 2015: 4. Print.

- Hladky, Gregory. “Malloy Doubts Law Happens This Year; Expense Could Be Key Obstacle; Police Body Cameras.” Hartford Courant 11 April 2015: A1. Print.

- Korte, Gregory. “Obama Signs “Blue Alert” Law to Protect Police.” USA Today, 19 May n. pag. Web. 28 May 2015. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2015/05/19/obama-blue-alert-law-bill-signing/27578911/.

- Li, David. “Obama Signs Bill Named for Slain NYPD Cops.” New York Post, 19 May 2015 n. pag. Web. 28 May 2015. http://nypost.com/2015/05/19/obama-signs-bill-named-for-slain-nypd-cops/.

- Martin, Joshua, & Waldo, Jr., Ralph. Black Against Empire. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013. Print.

- “Man Shoots, Kills Officer Wearing Body Cam.” CNN, 16 Jan. 2015. Web. 7 Sep. 2015.

http://www.cnn.com/videos/us/2015/01/16/newday-cuomo-officer-bodycam-fatal-shooting.cnn/video/playlists/caught-on-bodycam/. - Matyszczyk, Chris. “Why More People Are Training Their Cell Phones on Police.” CNET, 22 December 2013. n. pag. Web. 7 May 2015. http://www.cnet.com/news/why-more-people-are-training-their-cell-phones-on-police/.

- “Meme Database.” Know Your Meme, n.d. Web. 13 June 2015. http://knowyourmeme.com/memes.

- Mitchell, Kirk. “Denver Police Set Sights on Cameras.” Denver Post 28 August 2014: 4A. Print.

- “More Police Officers Being Outfitted with Body Cameras.” CBS Evening News, 26 July Web. 7 Sep. 2015. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/more-police-officers-being-outfitted-with-body-cameras/.

- “NAACP Urges Cell Phone Use to Fight Police Brutality.” CNN, 15 July 2009. Web. 16 May 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2009/US/07/15/naacp.police/index.html?eref=ib_us.

- Nakamura, Lisa. Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

- Nakamura, Lisa. “Gender and Race Online.” Society and the Internet: How Networks of Information and Communication Are Changing Our Lives. Ed. Mark Graham and William Dutton. London: Oxford University Press, 2014. 81-95. Print.

- Parenti, Christian. The Soft Cage: Surveillance in American from Slavery to the War on Terror. New York: Basic Books, 2003. Print.

- Perez, Anthony, Berg, Kimberly, and Myers, Daniel. “Police and Riots, 1967-1969.” Journal of Black Studies 34.2 (2003): 152-83. Print.

- Perry, Tony. “Eyes on the Body Cameras; by Year’s End, San Diego Plans to have Nearly 1,000 Officers Wearing the Devices.” Los Angeles Times 23 March 2015: 2. Print.

- “Police Body Camera Programs Raise New Challenges.” CBS Evening News, 3 May 2015. n. pag. Web. 7 Sep. 2015. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/police-body-camera-programs-raise-new-challenges/.

- “Police Body Camera Video Shows Suspect Shot After Struggle.” Fox 2 Now, 16 Jan.Web. 7 Sep. 2015. http://fox2now.com/2015/01/16/police-body-camera-video-shows-suspect-shot-after-struggle/.

- “Police: Chokehold Victim Eric Garner Complicity in Own Death.” Huffington Post, 5 December 2014. n. pag. Web. 7 Sep. 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/12/05/police-chokehold-eric-garner_n_6277790.html.

- Schlinkmann, Mark. “St. Charles Co. Delaying Body Cameras Until Legislature Clarifies What Public Can See.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 23 December 2014: A9. Print.

- “SF Mayor Wants All City Cops to Wear Body Cameras.” ABC News, 30 April 2015. n. pag. Web. 7 Sep. 2015. http://abc7news.com/news/sf-mayor-wants-all-city-cops-to-wear-body-cameras/689183/.

- Slipke, Darla. “Police Departments See Benefits from Body Cameras.” The Daily Oklahoman 28 November 2014: 11. Print.

- Smith, Kyle. “Baltimore Riot Mom is Mother of the Year.” New York Post, 28 April Web. 7 May 2015. http://nypost.com/2015/04/28/baltimore-riot-mom-is-mother-of-the-year/.

- “Street Video; Body Cameras Would Help Protect Police and Citizens.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 8 October 2014: B-6. Print.

- “Support Grows for Ferguson Officer Darren Wilson.” 11 Alive, n.d. n. pag. Web. 7 Sep. 2015. http://www.11alive.com/video/3736107710001/1/Support-grows-for-Ferguson-officer-Darren-Wilson.

- “Texas Pool Party Chaos: ‘Out of Control’ Police Officer Resigns.” CNN, 9 June 2015.Web. 7 Sept. 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/06/09/us/mckinney-texas-pool-party-video/.

- “Texas Releases Dashboard Video of Sandra Bland Arrest.” Time, 21 July 2015. Web. 7 Sept. 2015. http://time.com/3967005/sandra-bland-police-video-dashboard/.

- Vertesi, Janet. “The Problem with Police Body Cameras.” Time, 4 May 2015. Web. 7 May 2015. http://time.com/3843157/the-problem-with-police-body-cameras/.

- Watts, Eric, and Orbe, Mark. “The Spectacular Consumption of ‘True’ African American Culture: ‘Whassup’ with the Budweiser Guys?” Critical Studies in Media Communication 19.1 (2002): 1-20. Print.

- Wetherbee, Ben. “Picking Up the Fragments of the 2012 Election: Memes, Topoi, and Political Rhetoric.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society 5.1 (2015). n. pag. Web.

- Wilstein, Mark. “Oprah Called Baltimore Mom to Say: ‘I Understand Why You Did What You Did.’” Mediaite, 30 April 2015. Web. 7 May 2015. http://www.mediaite.com/tv/oprah-called-baltimore-mom-to-say-i-understand-why-you-did-what-you-did/.

Cover Image Credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/westmidlandspolice/9816063276

Armond R. Towns is an Assistant Professor of Culture and Communication at the University of Denver. He earned his PhD in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with focuses in media, rhetoric, performance, and cultural studies. His work intervenes in discussions of rhetoric, media and technology studies, and black studies. His research can be found in Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture and Transfers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies.

Armond R. Towns is an Assistant Professor of Culture and Communication at the University of Denver. He earned his PhD in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with focuses in media, rhetoric, performance, and cultural studies. His work intervenes in discussions of rhetoric, media and technology studies, and black studies. His research can be found in Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture and Transfers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies.