Book Review: Lipari’s Listening, Thinking, Being

Lipari, Lisbeth. Listening, Thinking, Being: Toward an Ethics of Attunement. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2014. Print.

With her book, Listening, Thinking, Being: Toward an Ethics of Attunement, Lisbeth Lipari’s explicit goal is to guide readers on a journey that will result in an out-and-out reconfiguration of our understanding of language, communication, speaking, and listening. Arguing that our ordinary, habitual ways of comprehending the seemingly simple, straightforward acts that comprise dialogue are not only inadequate but also fundamentally incorrect, she presents an alternative framework through which listening is posited as an ethical activity constitutive of human being.

With her book, Listening, Thinking, Being: Toward an Ethics of Attunement, Lisbeth Lipari’s explicit goal is to guide readers on a journey that will result in an out-and-out reconfiguration of our understanding of language, communication, speaking, and listening. Arguing that our ordinary, habitual ways of comprehending the seemingly simple, straightforward acts that comprise dialogue are not only inadequate but also fundamentally incorrect, she presents an alternative framework through which listening is posited as an ethical activity constitutive of human being.

Needless to say, Lipari has given herself a tremendous challenge, one that seeks to disrupt, or at least trouble, many of the conventions of Western thought. Indeed, she begins her analysis of the aural and its prevailing disregard as a philosophical topic with the Ancient Greeks, reminding us that like so many halves of so many binaries, listening is the neglected half of the speaking/listening duo. For Aristotle and Plato, speech forms the primary focus of rhetoric and language is but a poor reflection of the truth of thought.

However, in what will become a signature component of the book, Lipari counters the atomistic views of Aristotle and Plato with another tradition, turning to the fifth-century Indian philosopher of language Bhartṛhari and his depiction of communication as an indivisible union of language and thought in his work The Vākyapadīya. Awareness, for Bhartṛhari, was sensory, perceptual, and linguistic, and he used the theory of sphota to signify a holistic form of communication that does not divide speech into separate words put forward in a linear, temporal order. Sphota refers not to these single words arranged in a sentence that together create meaning but rather to the sentence in all of its multitudinous sounds as an undifferentiated whole. Bhartṛhari’s term becomes a link to a host of other theories of communication, especially in philosophy and ethics. Though her goals are formidable, Lipari’s book succeeds in explaining this very complex concept clearly and placing it within a vast historical context; however, her structuring of the book, with its privileging of echoes and resonances, and the density of the subject matter in places may be frustrating for some readers. Indeed, Lipari recognizes this and offers advice periodically: “If the material is new or unfamiliar to you, try not to get bogged down in the details—just keep reading with an open and akroatic mind, listing for holistic patterns, shapes, and relationships,” she suggests in chapter 2. Overall, however, anyone looking for an eloquent and passionate advocacy for listening and its relationship to thinking will find value in this book, especially for its deployment of a set of new terms designed to help us elucidate concepts that unite listening, ethics, and being.

Lipari opens her book with a description of the concept of akroatic thinking, which refers to a holistic form of listening incorporating harmonics, physics, and mathematics, but she only hints at the term’s full definition here to begin. Everything in the book is, in a sense, present in this opening, and the definition of akroatic thinking augured at the start will gradually grow layer by layer as we move toward the final chapter. The work we do with Lipari between commencement and completion will generate a dense field of concepts and approaches, priming us to comprehend a far more nuanced understanding of the term by the time we return to it in the conclusion. In this way, Lipari resists the linear temporality of the form of the book, as well as the customary sequential form of argumentation, crafting instead notes and echoes that reverberate throughout the pages.

In chapter 2, Lipari makes a distinction between hearing, which is etymologically tied to perception and a self that receives something, and the more invested act of listening, which is linked to attention and a focus on the other. The chapter goes on to explore listening as an embodied process and urges us to break out of habitual patterns of hearing to really engage both in listening and silence—to acknowledge them, investigate them, and experience them. She introduces a series of exercises that she uses with her students—being silent for an entire day, for example—and encourages us to listen attentively. “One of the greatest challenges to listening holistically is to interrupt the habitus, the habitual attributions of meaning that language and culture impose on our everyday experiences,” she asserts, urging us to disrupt these habits of listening (57).

The book’s third chapter identifies key attempts to theorize the relationship between language and thought, moving from Hindu scripture to Buddhism, Taoist thought, and the Greek mistrust of rhetoric. Bhartṛhari comes next, followed by Descartes and Kant. Lipari’s whirlwind tour distinguishes between atomistic and holistic models, repeatedly demonstrating the productive power of the holistic view. She highlights the “reverence for speech and sound as gifts from the divine” in the Vedas of Hinduism (60), the “paradoxical nature of consciousness and thought” among the Taoists of fifth-century China (66), and Plato’s distrust of language because “it made deception so very easy and because, even at best, language could only offer a secondhand image of truth” (66).

Chapter 4 continues the diagnostic impulse of the previous chapter, moving forward historically into modern thought and exploring the interplay between language and thinking. Chapter 5 uses this background to posit that communication is not a thing but a process that actively constitutes human being. Communication is generative, creative, and dialogic, argues Lipari; it emerges between people, transcending the boundaries that we imagine separate self and other and crafting spaces for new human capacities. “Because of the ways this intersubjective space creates a fissure in the sharp boundaries between self and other, it creates new possibilities for peaceful means of being with others,” she writes. “This space, when authentically freed from the control of any plan or agenda, can move us toward unimagined possibilities that far exceed the capacities of the individual participants” (134).

The subsequent chapter fully develops the concept of interlistening, demonstrating the complex imbrication of speaking and listening. Here, Lipari is concerned with the layering of speaking and listening in time; she hopes to understand thinking, listening, and speaking in a “relational synthesis,” a linking of synchrony and diachrony. To do so, she adopts the term “pluria” to designate the plurality of modalities at play, namely polymodality, polyphony, and polychronicity. “Polymodality” designates the intersubjective space between self and other, “polyphony” references the musical dimension of listening, and “polychronicity” acknowledges the role of time and tempo. Lipari’s goal here is to begin to articulate a lexicon for listening, to give it nuance and complexity that will not only underscore her thesis but also provide readers with greater subtlety of awareness and words with which to acknowledge and articulate a far greater palette of aural experience.

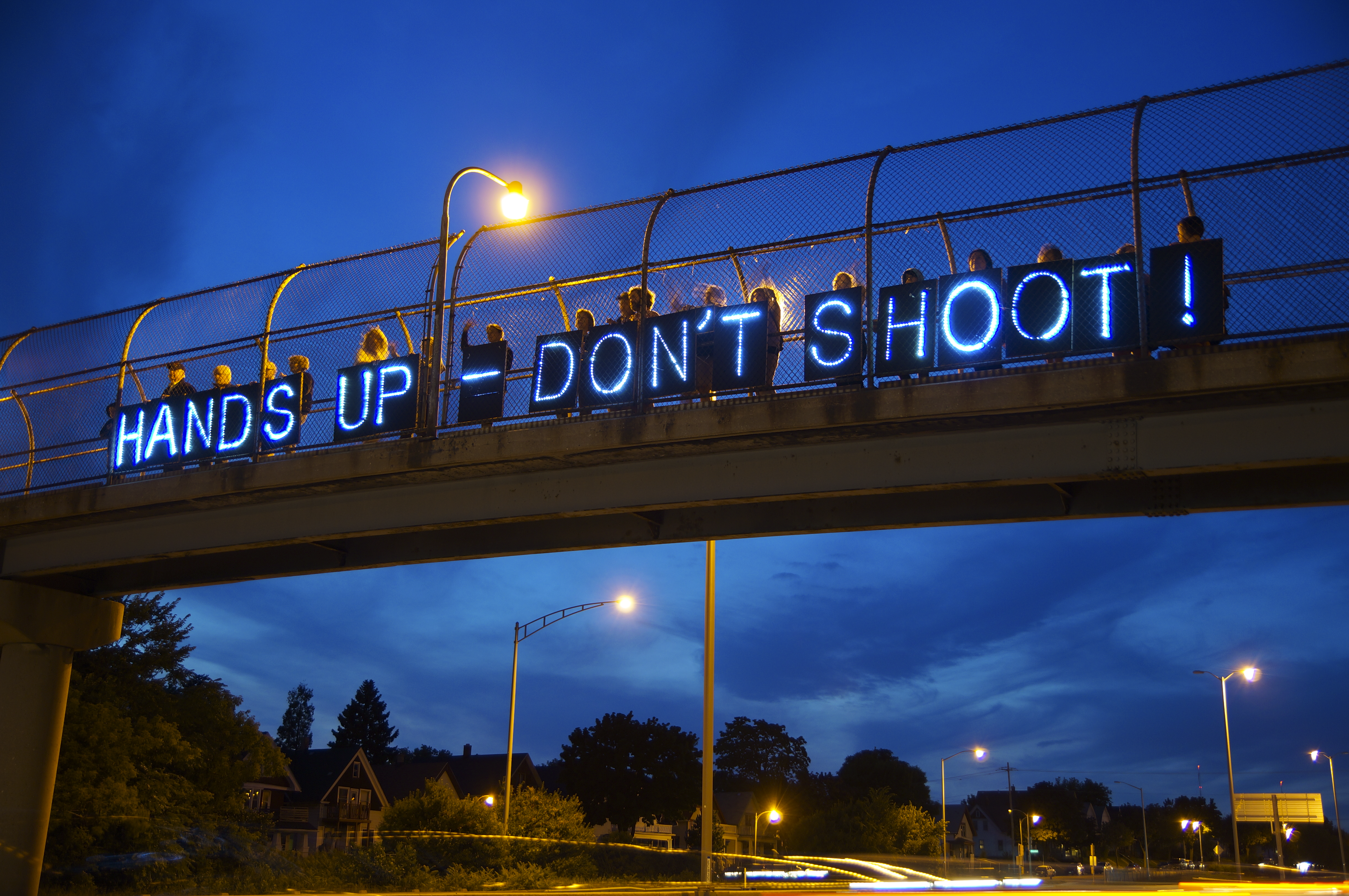

Chapter 7 turns to the ethics of listening, affirming the roles of empathy and an awareness of the radical alterity of the other as fundamental to what Lipari now refers to as a politics of listening. She develops the idea of “listening otherwise,” which refers to the acknowledgment and acceptance of the vulnerability of both self and other. Not only are we called forward to sense the suffering of others without the concomitant need to solve a problem or rationalize a situation, but we are also made aware of the need for our own vulnerability in the process; we are called forth to be both open and present. Underscoring the significance of listening otherwise, Lipari writes, “beyond the intellectual mysteries of listening, at heart this book centers on an ethical concern: what are the social, political, and cultural implications of our failure to listen for the other—that is, to listen without stealing our interlocutor’s possibilities and horizons of meaning?” (203). While she does not answer this question directly, listening otherwise requires letting go of our own sense of certainty and accepting the radical alterity of the other, and Lipari likens listening otherwise to the Buddhist notion of nonattachment.

As we approach this ability to listen otherwise, we begin the next stage in Lipari’s notion of communication: to listen others to speech. “Listening others to speech” refers specifically to the act of communication that requires some renunciation of the self, it is co-constitutive, and it is profoundly ethical through a dialogic process of intersubjectivity and inner listening.

Chapter 8 returns us to the beginning and akroatic thinking, but the founding term now vibrates in relation to so many other concepts; the result is what Lipari dubs an “attunement,” understood as a form of vibrational resonance. She illustrates this notion of attunement with two drawings by architect Manijeh Verghese of harmonic circles; they are generative and recursive and capture visually the sense of pulsation, reverberation, and beauty that characterize attunement.

This attunement defines the book overall. Lipari’s turn to Bhartṛhari and sphota in chapter 3 not only represents the shift from Western philosophy to Eastern thought, and by extension—for many Western readers—from mainstream to marginal, but also calls our attention to the book’s overall structure as itself a kind of sphota. True, the book moves sequentially, chapter-by-chapter, from start to finish; however, the argument is not so linear. Instead, it seems—appropriately enough—to pulse and vibrate, putting forth ideas that seem to hover and connect against a broad horizon spanning centuries and vast philosophical traditions. Lipari frequently signposts her reverberating argument, assuring us that a topic only mentioned at one point will be developed further along in the book, creating a series of deferrals and returns and a sustained sense of spiraling movement. The result is that the overall reading experience is profoundly spatial.

Lipari’s attention to listening within the field of rhetoric is aligned to some degree with the focus shared by several scholars on silence. Cheryl Glenn’s 2004 book Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence, for example, echoes the critique of the emphasis within rhetoric placed on the written and spoken. The book builds on Glenn’s earlier book Rhetoric Retold: Regendering the Tradition from Antiquity through the Renaissance (1997), arguing that this emphasis has resulted in a lack of attention to silence and, further, that this neglect is based on the historic and troubling association between silence and the feminine. Glenn goes on to argue for the rhetorical power of silence, using the experiences of several women and high-profile events as evidence.

Similarly, Krista Ratcliffe’s Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness (2006) develops a concept of rhetorical listening. Ratcliffe defines the term as “a trope for interpretive invention and more particularly as a code of cross-cultural conduct,” adding that it signifies “a stance of openness that a person may choose to assume in relation to any person, text, or culture” (17, emphasis original). More specifically, Ratcliffe is concerned with identification via gender and race and the ways in which rhetorical listening can facilitate communication across these differences. Her first chapter charts the work of several other scholars concerned with listening—including that of James Phelan, Andrea Lunsford, Victor Vitanza, and Michelle Ballif—but then suggests that despite this work, listening remains under-theorized. Glenn and Ratfliff went on to edit a collection of essays titled Silence and Listening as Rhetorical Arts (2011), and the assembled pieces contributed a series of specific textual analyses to the growing body of work dedicated to silence and listening.

Glenn and Ratcliffe, like Lipari, use the marginalized and critically neglected areas of communication to illuminate issues of power and oppression and, in this way, connect with Lipari’s overt interest in creating an ethics, one dedicated to “an awareness of and attention to the harmonic interconnectivity of all beings and objects” (2-3). This interconnectivity is dubbed “attunement,” and it, too, is a topic with a rich context in rhetoric. Perhaps the most obvious linkage is with Thomas Rickert’s recent book Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being (2013). Rickert joins other thinkers within the context of new materialism to argue that we need to rethink the relationship of humans to the world around us; he characterizes our era as one in which the boundaries between subject and object have dissolved and what remains is a kind of ambience through which we find ourselves attuned. Attunement in this case is linked to Martin Heidegger’s Stimmung, which “indicates one’s disposition in the world, how one finds oneself embedded in the world” (9). Like Rickert, Lipari shares an interest in a dissolution of boundaries, framing her project in terms of the holistic and atomistic perspectives that characterize one strand within the history of philosophy and linguistics. For Lipari, however, attunement is “the harmonic interconnectivity of all beings and objects” (2-3). In contrast with Rickert, she will emphasize the role of the harmonic rather than the ambient.

Lipari’s book also shares with Rickert’s an astonishing—and daunting—intellectual range, moving across vast territories within philosophy, linguistics, and rhetoric, and challenging readers to make complex connections and to trust Lipari as a guide. While some readers may not appreciate the spatial, sonic qualities that characterize the structure of the book, Lipari would perhaps argue that this is a result of a limited understanding of understanding itself, which, when reimagined, can prompt a different epistemology, one attentive to the plurality of sensual experience. Describing the power of intentional attention toward the end of the book, Lipari writes, “all too often, we ignorantly punctuate our experiences with a spatialized temporality, which, like a period at the end of a sentence, signals finality and completion and fails to account for the expanding oscillations of assonance and dissonance, fullness and emptiness, which are better expressed by the musical temporality of a comma, or a breath.” These words invite us to attend to multiple temporalities and voices, but they, again, capture Lipari’s own writing, its musicality and its elusiveness, an embodiment of her ideas on the page.

Works Cited

- Glenn, Cheryl, and Krista Ratcliffe, eds. Silence and Listening as Rhetorical Arts. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2011. Print.

- Glenn, Cheryl. Rhetoric Retold: Regendering the Tradition from Antiquity through the Renaissance. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1997. Print.

- —. Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2004. Print.

- Ratcliffe, Krista. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2006. Print.

- Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 2013. Print.

Holly Willis is a faculty member in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, where she serves as the Chair of the Media Arts + Practice Division. Her research explores the intersections of media art, graphic design and rhetoric, and the ways in which they inform contemporary scholarly practices. She writes frequently on avant-garde film, video and new media, and is the author of New Digital Cinema: Reinventing the Moving Image and the forthcoming book, Fast Forward: The Future(s) of the Cinematic Arts.

Holly Willis is a faculty member in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, where she serves as the Chair of the Media Arts + Practice Division. Her research explores the intersections of media art, graphic design and rhetoric, and the ways in which they inform contemporary scholarly practices. She writes frequently on avant-garde film, video and new media, and is the author of New Digital Cinema: Reinventing the Moving Image and the forthcoming book, Fast Forward: The Future(s) of the Cinematic Arts.