An Annotated Bibliography of LGBTQ Rhetorics

Introduction

The early 1970s marked the first publications both in English studies and communication studies to address lesbian and gay issues. In 1973, James W. Chesebro, John F. Cragan, and Patricia McCullough published an article in Speech Monographs exploring consciousness-raising by members of Gay Liberation. The following year, Louie Crew and Rictor Norton’s special issue on The Homosexual Imagination appeared in College English. In the four decades since these publications, the body of work in rhetorical studies within both fields that addresses lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (hereafter LGBTQ) issues has grown quite drastically. While the first few decades marked slow and interstitial development of this work, it has burgeoned into a rigorous, exciting, and diverse body of literature since the turn of the century—a body of literature that shows no signs of slowing down in its growth.

An annotated bibliography of rhetorical studies scholarship that addresses LGBTQ issues and queer theory would have been quite manageable only a decade ago. In 2001, Frederick C. Corey, Ralph R. Smith, and Thomas K. Nakayama delivered a compiled bibliography of scholarship in communication studies that addressed LGBTQ issues at the National Communication Association Convention. This bibliography compiled a list of 66 journal articles in communication studies published between 1973 and 2001 (Corey, Smith, and Nakayama; Yep 15) that revealed a slowly growing field.

The development of such a rich body of work in rhetorical studies, especially over the last decade, has warranted an annotated bibliography of rhetorical scholarship that addresses LGBTQ issues and incorporates queer theory. This bibliography is not the first in rhetorical studies to attempt to collect work that addresses LGBTQ rhetorical scholarship: We want to acknowledge previous bibliographic work, including Corey, Smith, and Nakayama’s; Rebecca Moore Howard’s; and Jonathan Alexander and Michael J. Faris’s. While these bibliographies have been useful for scholars interested in LGBTQ rhetorical studies, they have quickly become outdated, are limited in their disciplinarity—either bibliographies in communication studies or in English studies—and do not provide annotations for readers.

This bibliography, then, is motivated by a series of exigencies. First and foremost is visibility and accessibility of research and scholarship in LGBTQ rhetorics. As Charles E. Morris III and K. J. Rawson note, while queer scholarship in rhetorical studies has been quite visible over the last decade and queer theory has been quite influential across the humanities and social sciences, “rhetorical scholars have been much slower in responding to the ‘queer turn’” (74). This bibliography, we hope, can lend visibility to this body of work.

Thus, this bibliography serves a number of purposes. It should assist graduate students new to the field and researchers already far into their careers in understanding the rich history of sexuality studies and rhetorical studies, finding relevant scholarship, and developing exigencies in research that they can exploit for their own scholarship pursuits. While the field has been growing, it can be difficult to find queer rhetorical work dispersed across a variety of journals. If you had asked either of us as we began our graduate programs if there was much scholarship or even interest in queer issues in rhetorical studies, then we would have been able to reference a few articles—but not much else: Rhetoric studies seemed incredibly straight. And, in many ways, it still does. Graduate students are often encouraged to study heteronormative theory and, we might say, are trained to identify with it. Nakayama and Corey write, “Queer academics want to join the ranks” and do so through “idoliz[ing] heteronormative theories”—theories that have marginalized, ignored, and marked queer sexuality as deviant and abnormal (324). While the field is more inclusive of queer approaches than it was a decade ago when Nakayama and Corey published those words—thanks, in large part, to those cited in this bibliography—, many are still resistant to queer approaches. Professionalization in graduate school often discourages queering the field, as Alyssa A. Samek and Theresa A. Donofrio argue. This bibliography should be useful to graduate students—and to researchers already far into their careers—for understanding the rich work that has already been done in sexuality studies and rhetoric.

Additionally, we hope to encourage more engagement in rhetorical studies with sexuality from a variety of rhetorical approaches. This bibliography might also be useful to scholars looking to publish in queer rhetorics to identify journals that have been particularly open or hospitable to certain queer approaches.

Further, this bibliography should be useful for teachers of graduate seminars who want to incorporate sexuality studies or queer approaches to rhetorical studies in their seminars: Students in courses on feminist studies, identity and rhetoric, methodologies, historiography, public memory, composition studies, public rhetoric, public address, social movements, digital writing, and more can benefit from this bibliography.

Another important exigence of this project is the historical split along disciplinary lines between English studies and communication studies. We follow calls by Steven Mailloux, Michael Leff, and others to attempt to bridge the divide between these two disciplines. This divide goes back nearly a century, to 1917, when communication scholars left the National Association of Teachers of English to form the National Association of Academic Teachers of Speech, now the National Communication Association (Mountford 409; see Mountford for a discussion of this disciplinary split as well as attempts at and prospects for rapprochement). Mailloux notes—and we agree—that “[a] multi-disciplinary coalition of rhetoricians will help consolidate the work in written and spoken rhetoric, histories of literacies and communication technologies, and the cultural study of graphic, audio, visual, and digital media” (23). Leff has encouraged us to “listen carefully and learn much more about the aspirations, idiosyncracies [sic], and anxieties of our rhetorical neighbors” (92). More recently, “The Mt. Oread Manifesto on Rhetorical Education,” published in Rhetoric Society Quarterly, calls attention to our disciplines’ “common interest” (2) to develop an integrated rhetorical curriculum. This disciplinary split is readily apparent in the scholarship listed in this bibliography: English studies scholars have shown a stronger interest in writing pedagogy (including in digital environments) and literacy whereas communication studies scholars have been drawn more toward studying popular culture, public memory, archives, and social movements (though these lists are neither exhaustive nor exclusive of each other). While these bodies of scholarship certainly speak to each other implicitly, explicit connections are few and far between.

Scholars in both fields, we believe, can benefit from the groundbreaking and recent work across rhetorical studies. Perhaps queer rhetorical studies can begin to serve as a model for bridging this disciplinary divide, as Roxanne Mountford notes feminist rhetoricians have done (419). Some of this work has already begun. For instance, the Rhetoric Society of America’s 2009 Summer Institute featured a workshop on “Queer Rhetorics,” led by Karma R. Chávez, Charles I. Morris III, and Isaac West, that drew participants from both sides of rhetoric.

In what follows, we provide a brief overview of queer theory for readers unfamiliar with this body of work, outline a brief history of how rhetorical studies has addressed and approached issues of sexuality and gender nonconformity, discuss our methods for compiling this bibliography, and preview the organization of the bibliography.

A Brief Introduction to that “Tinkerbell,” Queer Theory

In the opening pages of Nikki Sullivan’s A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory, she notes that queer theory often resists definition—and, indeed, it has become cliché to claim so. But such claims risk granting queer theory a “‘Tinkerbell effect’; to claim that no matter how hard you try you’ll never manage to catch it because essentially it is ethereal, quixotic, unknowable” (v). Here, we would like to provide a modest attempt at defining queer theory, understanding that the field is much more complex and rich than we can attest to in such a small space. In short, queer theory is a body of work—informed by a variety of methodologies and theoretical lenses—that examines and critiques discourses of sexuality with the goal of transforming society.

The term “queer theory” was first anachronistically applied to work in the late 1980s and early 1990s that did not explicitly claim to be queer theory. This work argued that social theory and feminist critiques were inadequate if they did not treat sexuality as its own category of analysis. We can briefly chart queer theory’s genealogical roots in feminism, poststructural theory, vernacular theory from queer activism, and queer of color critiques. Feminists like Gayle Rubin, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and Judith Butler, in now canonical texts, argued that sexuality warranted its own investigation separate from gender and that feminism could not successfully challenge patriarchy without radical changes in sexuality. As Sedgwick writes in Epistemology of the Closet, “an understanding of virtually any aspect of modern Western culture must be, not merely incomplete, but damaged in its central substance to the degree that it does not incorporate a critical analysis of modern homo/heterosexual definition” (1).

Second, queer theory is informed by poststructuralist theory, particularly the work of Michel Foucault. In The History of Sexuality, he denaturalizes assumptions about sexual identities and repressed desires. As a result, he provides a theoretical framework for the discursive construction of sexuality and the relationships between power, discourse, and sexuality. The third genealogical ancestor for queer theory is queer social movements like Queer Nation and ACT UP. In the 1990s, these movements advanced political and theoretical critiques of static gay and lesbian identities and questioned the relationship between sexuality, the nation, and citizenship (see Rand). Fourth, queer theory has been informed by queer of color critiques from scholars and activists like Gloria Anzaldúa and E. Patrick Johnson, who have argued for approaching identities as intersectional and attending to the particularities of lived experiences along axes of difference.

As Hanson Ellis summaries, “[q]ueer theory is the radical deconstruction of sexual rhetoric.” Queer theory in many ways challenges the commonsense norms and assumptions most people think with (doxa) regarding gender and sexuality. It “attempts to clear a space for thinking differently about the relations presumed to pertain between sex/gender and sex/sexuality, between sexual identities and erotic behaviors, between practices of pleasure and systems of sexual knowledge” (Hall and Jagose xvi). Queer theory differs from gay and lesbian studies in a few ways. Michael Warner, in his introduction to Fear of a Queer Planet, calls for a new queer politics that rejects a “liberal-pluralist” approach to assimilating LGBT persons and concerns into a capitalist society (xxv-xxvi). Sedgwick’s distinction between minoritizing logic and universalizing logic is useful in helping to understand queer theory. Whereas gay and lesbian approaches focus on the needs and interests of a minority—a minoritizing logic—a universalizing logic understands sexuality “as an issue of continuing, determinative importance in the lives of people across the spectrum of sexualities” (1).

Thus, queer theorists ask a variety of questions: How are identities constructed and validated, how do discourses about sexuality circulate and reaffirm or reassert power, how do queers or other marginalized sexual and gendered beings engage in “world-making” (Berlant and Warner 558)? This investment in world-making has meant that many queer theorists embrace anti-normativity. It is important to note that anti-normativity here is not embraced simply for the sake of anti-normativity itself but because, as Lauren Berlant and Warner explain, normativity continues to value statistical mass (and thus heterosexuality) and cramps spaces of sexual culture (557).

Methods for Building the Bibliography

Drawing from prior bibliographic work (Alexander and Faris; Corey, Smith, and Nakayama; Howard), citation-chasing, and searching the archives of over 60 journals in English studies and communication studies, we culled hundreds of citations down to the ones included in this bibliography. We tried to strike a balance of scope between comprehensiveness and accessibility. This balance necessarily meant being selective about what work to include.

Importantly, this bibliography is a bibliography of work by rhetoric scholars. We debated what sort of bibliography this should be: One that introduces queer theory to the field, or one that assists rhetoric scholars in understanding how the field has already been addressing sexuality over the last 35 years. Initially, it seemed unthinkable to put together a collection on queer rhetorics and not include the queer theorists whose volumes we had so many times turned to across publication, teaching, and conference presentation work. A queer rhetorics bibliography without Foucault, Butler, Sedgwick, Warner, David M. Halperin, Anzaldúa, José Esteban Muñoz, and J. Jack Halberstam? And yet, we also reasoned that many readers interested in the work shared here would have a working awareness of these scholars as LGBT and queer scholars, and even those readers who did not have this awareness would notice here the repeating nature of references to these foundational works in the rhetoric-oriented works we did cover. (Readers not familiar with queer theory can reference our discussion above and our Works Cited as a resource.)

And so, ultimately we decided to narrow our focus solely to scholarship in rhetorical studies, despite the rhetorical nature of queer theory. Indeed, we contend, along with Jonathan Alexander and Michelle Gibson that queer theory is “intimately rhetorical” (7).

Bibliographic work is in many ways disciplinary work, attending to and demarcating the boundaries of “what counts” as rhetorical, as related to sexuality, and as queer. Despite rich histories of LGBTQ scholarship in media studies and performance studies within communication departments, we have chosen not to include much of that scholarship (with a few exceptions), in part to make this project more manageable for readers. Additionally, what sort of research counts as rhetorical and as queer can be hotly debated. Certainly, due to both our disciplinary trainings (Michael in a rhetoric and composition graduate program in English and Matt in a stand-alone rhetoric and writing studies program), there will be gaps and unintentional exclusions, which we can only attribute to our “trained incapacities” (Burke 7).

Sketching Out Approaches and a History to Sexuality Studies in Rhetoric

It would be disingenuous to claim that rhetorical studies has one singular, coherent approach to studying sexuality and rhetoric. And indeed, creating a comprehensive heuristic for even the multiple, various, and sometimes even conflicting approaches within rhetorical studies is a difficult task, given the variety of scholarship conducted in English studies and communication studies over the last four decades. However, Sedgwick’s distinction between minoritizing logics and universalizing logics (discussed above) is useful in understanding two distinct styles of approaches to incorporating sexuality into rhetorical studies. We identify three “stages” to scholarship in queer rhetorics, though by no means are these stages meant to be discrete. Indeed, minoritizing logics are still at play in more recent scholarship, and some early work took universalizing approaches.

Early work in the field largely took a minoritizing approach to sexuality, focusing on gay and lesbian identities (and occasionally transgender or queer ones, though rarely bisexuality). This work focused on visibility, coming out, identifying homophobia, and incorporating LGBT perspectives and rhetoric into teaching and scholarship.

A second stage of queer rhetorical work began to draw on queer theory and take a more universalizing approach to sexuality, understanding that sexuality is an aspect of all our lives, is present (though usually unnoticed) in pedagogical practice and theory, and is an approach useful to all rhetorical studies. These approaches turned to heterosexuality and heteronormativity as discursive constructions and began to critique and challenge rhetorical theory.

The third, most recent stage of queer rhetorical studies is the move to speak to other disciplines, including queer theory. That is, rather than solely import queer theory into rhetorical studies, scholars are beginning to show how queer theory and other disciplines can learn from rhetorical theory. This approach is not novel: As early as 1996, Robert Alan Brookey was arguing that while queer theory has insights for rhetorical studies, rhetorical studies can also contribute to queer theory because of its approach to “the particular” (45). But while Brookey made this claim nearly two decades ago, it is not until much more recently that queer rhetorical scholars have taken up this charge seriously. Isaac West’s Transforming Citizenship provides an example of this approach. In critiquing queer theory’s radical anti-normative stance, he offers rhetorical studies as an approach to mediate decontextualized queer theory resistances to “the norm.” West understands rhetoric’s focus on “contingency” as an opportunity to provide nuance and situatedness to rhetorical action and agency. “Without this awareness of contingency,” he writes, “the anti-essentialist qualities of queerness are lost to a predetermined and fixed sense of radical anti-normativity incapable of accommodating anything other than facially recognizable acts of being against something, most notably, the norm” (25-6).

Again, this brief tour through the history of the field oversimplifies but provides one heuristic (among many) for approaching queer rhetorical studies.

Navigating this Bibliography

As with so many tasks around compiling this bibliography, organizing the work defied an easy answer or taxonomy. We have chosen two organizational schemes for this bibliography: chronological and thematic. The first section shares work from 1973 to 1995. We were able to see a visible increase in LGBT rhetorical work throughout the 1990s, and 1995 served as a somewhat arbitrary year to distinguish earlier work from later work. 1995 saw the publication of Harriet Malinowitz’s Textual Orientations, which served as a touchstone for composition studies. Shortly afterward, in 1997, Jonathan Alexander published “Out of the Closet and into the Network” in Computers and Composition, one of his first publications in LGBTQ composition studies. In communication studies, 1996 marked the publication of Charles E. Morris III’s “Contextual Twilight/Critical Liminality,” an early contribution to queering methodologies. Additionally, Corey C. Frederick and Thomas K. Nakayama published their controversial “Sextext” in Text and Performance Quarterly in 1997. Thus, we see the mid-1990s as a “turning point” or “ramping up” moment for queer rhetorics—one among other possible points of departure.

The remaining ten sections of the bibliography are organized thematically, according to broad and admittedly overlapping categories. The bibliography, then, is organized according to the following eleven sections:

Section 1: LGBTQ Perspectives: 1973-1995

Section 2: Disciplinary Boundaries and Methodologies

Section 3: Pedagogical Practices and Theories

Section 4: Composition Studies

Section 5: History, Archives, and Memory

Section 6: Publics and Counterpublics

Section 7: Rhetorics of Identity

Section 8: Rhetorics of Activism

Section 9: Discourses of HIV/AIDS

Section 10: Popular Culture and Rhetoric

Section 11: Digital Spaces

Because these sections overlap, we have also provided tags for each annotation; readers seeking to find related work can search through the bibliography for related tags. A list of tags is below.

A Final Note

It has been incredibly rewarding to read such a diverse array of scholarship that has approached sexuality and queered rhetorical studies over the last four decades. Even as we researched, wrote, compiled, and organized, we saw concurrently just how useful this resource is. It is, to say the least, reassuring to know that we have created something that seemed to us so useful.

It is important to us to note that we see this bibliographic work as a kairotic space—a first for rhetoric studies in its comprehensive nature, but by no means a canonical text. We hope this bibliography is productive for scholars who hope to continue to challenge the field in terms of methods, methodologies, epistemologies, and modes of publishing—digital and print.

Tags

ACT UP

Activism

Affect

Age

Agency

Allies

Archives

Bodies

Camp

Citizenship

Class

Closet

Collective Identity

Coming Out

Composition

Confessional

Counterpublics

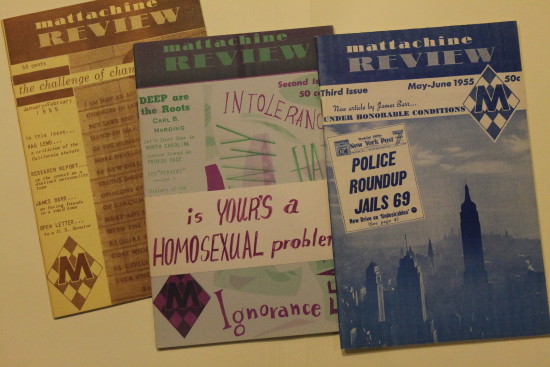

Daughters of Bilitis

Desire

Digital

Disability

Disciplinarity

Drag

Ethics

Etiology

Ex-Gay

Feminism

Futurity

Gay Rights

Gender

Heteronormativity

Histories

HIV/AIDS

Homophobia

Identity

Immigration

Intersectionality

Legal

Lesbian

Literacy

Literature

Materiality

Media

Medical

Memory

Misogyny

Queer Nation

Passing

Pedagogy

Performativity

Politics

Popular Culture

Privacy

Psychoanalysis

Publics

Public Address

Race

Regionalism

Religion

Representation

Safe Spaces

Sextext

Silence

Technical Communication

Tolerance

Violence

Visibility

Visual Rhetoric

Works Cited

- Alexander, Jonathan, and Michael J. Faris. “Issue Brief: Sexuality Studies.” National Council of Teachers of English. 2009. Web.

- Alexander, Jonathan, and Michelle Gibson. “Queer Composition(s): Queer Theory in the Writing Classroom.” JAC 24.1 (2004): 1-21. Print.

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987. Print.

- Berlant, Lauren, and Michael Warner. “Sex in Public.” Critical inquiry 24.2 (1998): 547-566. Print.

- Brookey, Robert Alan. “A Community like Philadelphia.” Western Journal of Communication 60.1 (1996): 40-56. Print.

- Burke, Kenneth. Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose. 3rd ed. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990. Print.

- Chesebro, James W., John F. Cragan, and Patricia McCullough. “The Small Group Technique of the Radical Revolutionary: A Synthetic Study of Consciousness.” Speech Monographs 40.2 (1973): 136-146. Print.

- Corey, Frederick C., Ralph R. Smith, and Thomas K. Nakayama. Bibliography of Articles and Books of Relevance to G/L/B/T Communication Studies. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Communication Association, Atlanta, GA. Nov. 2001.

- Ellis, Hanson. “Gay Theory and Criticism: 3. Queer Theory.” The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism. 2nd ed. Eds. Michael Groden, Martin Kreiswirth, and Imre Szeman. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 2005. Web.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. Volume 1. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage, 1990. Print.

- Hall, Donald E., and Annamarie Jagose. Introduction. The Routledge Queer Studies Reader. Eds. Donald E. Hall and Annamarie Jagose, with Andrea Bebell and Susan Potter. London: Routledge, 2013. xiv-xx. Print.

- Howard, Rebecca Moore. “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Language, Discourses and Rhetorics.” Rebecca Moore Howard: Writing Matters. 2014. Web.

- Johnson, E. Patrick. “‘Quare’ Studies, or (Almost) Everything I Know About Queer Studies I Learned from My Grandmother.” Text and Performance Quarterly 21.1 (2001): 1-25. Print.

- Leff, Michael. “Rhetorical Disciplines and Rhetorical Disciplinarity: A Response to Mailloux.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 30.4 (2000): 83-93. Print.

- Mailloux, Steven. “Disciplinary Identities: On the Rhetorical Paths Between English and Communication Studies.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 30.2 (2000): 5-29. Print.

- Morris, Charles E., III, and K. J. Rawson. “Queer Archives/Archival Queers.” Theorizing Histories of Rhetoric. Ed. Michelle Ballif. Carbondale: University of Illinois, 2013. 74-89. Print.

- Mountford, Roxanne. “A Century After the Divorce: Challenges to a Rapprochement Between Speech Communication and English.” The SAGE Handbook of Rhetorical Studies. Eds. Andrea A. Lunsford, Kirt H. Wilson, and Rosa A. Eberly. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2009. 407-422. Print.

- “The Mt. Oread Manifesto on Rhetorical Education 2013.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 44.1 (2014): 1-5. Print.

- Nakayama, Thomas K., and Frederick C. Corey. “Nextext.” Queer Theory and Communication: From Disciplining Queers to Queering the Discipline(s). Eds. Gust A. Yep, Karen E. Lovaas, and John P. Elia. Binghamton, NY: Haworth, 2003. 319-334. Print.

- Rand, Erin J. Reclaiming Queer: Activist and Academic Rhetorics of Resistance. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2014. Print.

- Rubin, Gayle. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality. Ed. Carole S. Vance. Boston: Routledge, 1984. 267-319. Print

- Samek, Alyssa A., and Theresa A. Donofrio. “‘Academic Drag’ and the Performance of the Critical Personae: An Exchange on Sexuality, Politics, and Identity in the Academy.” Women’s Studies in Communication 36.1 (2013): 28-55. Print.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley: U of California P, 1990. Print.

- Sullivan, Nikki. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. New York: New York U P, 2003. Print.

- Warner, Michael. Introduction. Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory. Ed. Michael Warner. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1993. vii-xxxi. Print.

- West, Isaac. Transforming Citizenships: Transgender Articulations of the Law. New York: New York U P, 2014. Print.

- Yep, Gust A. “The Violence of Heteronormativity in Communication Studies: Notes on Injury, Healing, and Queer World-Making.” Queer Theory and Communication: From Disciplining Queers to Queering the Discipline(s). Eds. Gust A. Yep, Karen E. Lovaas, and John P. Elia. Binghamton, NY: Haworth, 2003. 11-59. Print.

Section 1: LGBTQ Perspectives: 1973-1995

Chesebro, James W., ed. Gayspeak: Gay Male & Lesbian Communication. New York: Pilgrim, 1981. Print.

This early edited collection about communication practices takes as its premise that homosexuality is not solely a biological issue but is rather a social issue largely mediated by communication. Contributions to this collection explore both verbal and nonverbal communication of gays and lesbians as well as antigay communication. The 23 chapters are divided into six sections: (1) explorations of the social meanings of homosexual, gay, and lesbian; (2) analyses of in-group communication and how that communication creates intersubjective experiences; (3) discussions of the concept of homophobia, its causes, and its effects; (4) analyses of public discourses about homosexuality in the media, social sciences, arts, and education; (5) rhetorical analyses of gay and lesbian liberation social movements; and (6) analyses of the rhetoric of the gay civil rights debate by both pro-gay and antigay forces. Chesebro’s edited collection marks a shift in understanding sexuality as a social and communicative issue instead of a primarily biological or moral one.

Tags: Activism, Collective Identity, Etiology, Gay Rights, Homophobia, Identity, Media, Representation

Chesebro, James W., John F. Cragan, and Patricia McCullough. “The Small Group Technique of the Radical Revolutionary: A Synthetic Study of Consciousness Raising.” Speech Monographs 40.2 (1973): 136-46. Print.

Chesebro, Cragan, and McCullough examine the small group activities of revolutionary members of Gay Liberation that occur before their public confrontations. These sessions involve consciousness-raising, which entails the reformulation of identities and the development and commitment to new values. Chesebro, Cragan, and McCullough identify stages of consciousness-raising in these meetings, focusing on the functions of these stages and the rhetorical tactics employed. They chart four stages of consciousness-raising during the meetings: (1) initial claims about identity and oppression, largely focused on individual experiences and the past; (2) the development of a group identity in opposition to straight society; (3) the creation of new values for the group; and (4) identification with other oppressed groups (139-43).

Tags: Activism, Collective Identity, Identity

Crew, Louie, and Karen Keener. “Homophobia in the Academy: A Report of the Committee on Gay/Lesbian Concerns.” College English 43.7 (1981): 682-89. Print.

In 1976, the National Council of Teachers of English passed a resolution (just barely) opposing discrimination against gays and lesbians. It charged the Committee on Lesbian and Gay Concerns to achieve two goals: (1) create programming about literature and pedagogy for the national convention and (2) document discrimination within the profession (682-83). Crew and Keener share the results of a survey conducted by the Committee of NCTE members. Nearly twelve percent of those surveyed (K-12 through college teachers) reported that someone they knew (either a student or educator) “received unfair treatment because he or she was thought to be gay,” including being fired (683). Reported examples include hostility from department chairs, being put on leave after entrapment by police (homosexual sex was illegal in most states in 1981), not considering gay applicants for faculty positions, disparaging remarks from other teachers and students, and college administrators refusing to certify teachers they believed were gay (684-86). Crew and Keener stress that many of these teachers were effective, loved, and even praised for their talented teaching but often lost their jobs for real or perceived homosexuality (685-86). They remark that “[t]he prognosis for reforming the institutions themselves, even otherwise liberal centers of urban culture, seems grim” (686-87).

Tags: Academia, Homophobia, Pedagogy

Crew, Louie, and Rictor Norton, eds. The Homosexual Imagination. Spec. issue of College English 36.3 (1974): 271-412. Print.

Crew and Norton’s 1974 special issue of College English calls attention to the “generally hostile environment” that homosexual literature is written and read within (272) and includes contributions that “‘celebrate the homosexual imagination’ from ‘a pro-gay viewpoint’” (273). Crew and Norton critique the scholarly silence on and censorship and suppression of homosexual literature as well as the outright homophobic responses to homosexual literature (277-84). They also critique the heterosexual bias behind “objectivity” (284-85) and of pedagogy in English classrooms (286-88).

This special issue includes the following pieces: an interview with Eric Bentley, an outspoken gay drama critic; Jacob Stockinger’s assessment of the state of gay literary criticism; Dolores Noll’s narrative of coming out as a lesbian at Kent State University and being faculty advisor for the Kent Gay Liberation Front; Ron Schreiber’s experiences co-teaching a course on homosexuality and Western literature; Arnie Kantrowitz’s experiences teaching a “homosexuals and literature” course at State Island Community College; an anonymous contribution from a graduate student narrating his struggles as a gay teacher and emerging scholar; analyses of homosexuality in the military within literature by Roger Austen, Oscar Wilde and E. M. Forster by David Jago, and John Rechy’s City of Night by James R. Giles; Jon L. Clayborne’s exploration of negative gay representations in African American drama; an analysis of gay slang by Julia P. Stanley; an interview with Allen Ginsberg excerpted from the gay liberation magazine Gay Sunshine; and a “Checklist of Resources.” While the special issue approached English studies mostly through the lens of literature, it marks an important moment in the history of LGBTQ scholarship in the discipline. The special issue garnered numerous responses from readers; see “Comments on the Homosexual Imagination” in College English 37.1 (1975): 62-85.

Tags: Coming Out, Disciplinarity, Literature, Pedagogy, Race

Cummings, Kate. “The Double Scene of Televised AIDS Campaigns.” Queer Rhetoric. Spec. issue of Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 13.3-4 (1992): 67-77. Print.

Cummings analyzes televised HIV/AIDS campaigns of the late 1980s and early 1990s, arguing that they necessarily excluded queers and condoms in order to reassert national, chaste heterosexuality. Drawing on Freudian and Lacanian pyschoanalysis, Cummings explains that the earliest educational campaigns included images of gay men and condoms, which allowed straight viewers to associate condoms with queerness and see them both as threatening, perverse others. Condoms, then, underwent a semiotic shift, from association with safe heterosexual sex to association with queerness, a double association that had to be expelled from media campaigns. She turns to Magic Johnson’s 1991 HIV prevention media campaign, showing how the specter of queer sexuality led Johnson to drop his safe sex campaign, admit that promiscuity is a moral failure, and advocate for abstinence. Thus, heterosexual citizenship is supported and reaffirmed as morally chaste and not perverse.

Tags: Bodies, Citizenship, Histories, HIV/AIDS, Media, Psychoanalysis, Popular Culture

Darsey, James. “From ‘Gay Is Good’ to the Scourge of AIDS: The Evolution of Gay Liberation Rhetoric, 1977-1990.” Communication Studies 42.1 (1991): 43-66. Print.

Darsey examines the rhetoric of gay social movements from 1977 to 1990 as a contribution to social movement rhetorical theory. Darsey organizes his rhetorical history through “catalytic events,” or those significant events that “provide the appropriate conditions for discourse” (46). He then highlights the value appeals central to gay rhetoric in response to those events. Darsey identifies three catalytic events that the gay liberation movement responded to rhetorically: Anita Bryant’s 1977 Save Our Children campaign, the rise of the Moral Majority and right-wing evangelicalism, and the AIDS crisis (47). The success of Bryant’s campaign casted doubt on the idea of liberal progress being inevitable, and gay rhetoric responded predominantly through appeals to unity in the late 1970s as well as through appeals to determination and safety (48-50). As Bryant’s national prominence was replaced by the Moral Majority with Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, gay rhetors responded by extending and shifting the appeals of the late 1970s (51-5). In response to the developing AIDS crisis in the early 1980s, gay rhetoric shifted in tone more toward appeals to justice (56).

Tags: Activism, Gay Rights, HIV/AIDS, Religion

Dean, Tim. “Bodies that Mutter: Rhetoric and Sexuality.” Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 15.1-2 (1994): 80-117. Print.

Tim Dean critiques a paranoid style of queer politics and queer theory, especially Judith Butler’s theory of performativity and use of psychoanalysis, in order to develop a theory of sexuality and rhetoric that is “antifoundational and antirhetoricalist” (84). Dean argues that poststructuralist theory too quickly claims that “sex is fully mediated,” equating sex and rhetoric and thus ignoring desire (82). Dean turns to Lacanian psychoanalysis to argue that sexuality is not rhetorical: “although desire is ‘in’ language, desire is not itself linguistic” (84). Put differently, psychoanalytic accounts like Butler’s and Lee Edelman’s theorize a subject created by language and identification (the psychoanalytic symbolic and imaginary) but not subjects of desire (90). Dean argues that his approach is political in that, while Edelman and Butler place resistance in deconstruction and performativity, Dean sees resistance in psychoanalysis (93, 104). Whereas poststructuralism theorizes sexuality in terms of gender binaries, Lacanian psychoanalysis theorizes desire in terms of loss, independent of gender (95). While desire is a product of language’s disruption on the body, it is not linguistic: “desire is predicated on the incommensurability of body and subject” (100). In this way, Dean attempts to rescue Lacan from claims that his theory is heterosexist (95).

Tags: Bodies, Desire, Performativity, Psychoanalysis

Dow, Bonnie J. “AIDS, Perspective by Incongruity, and Gay Identity in Larry Kramer’s ‘1,112 and Counting.’” Communication Studies 45.3-4 (1994): 225-40. Print.

Dow examines Larry Kramer’s 1983 essay “1,112 and Counting,” a central rhetorical text to the development of AIDS activism. Using Kenneth Burke’s concept of “perspective by incongruity,” Dow argues that Kramer’s essay worked to change gays’ perceptions of AIDS and themselves and to take action regarding AIDS. Through anger and shock, Kramer’s essay works to make gay readers’ denial of AIDS seem incongruous with the startling reality of the AIDS epidemic (232). Further, Kramer’s rhetoric highlighted the contradiction between responsibilities of government agencies and their inactions, forcing readers to draw political conclusions that gay men are disenfranchised (233). Kramer also makes gay men’s focus on sex rather than politics seem incongruous with life, equating silence and the closet with death and self destruction (236). These strategies of perspective by incongruity set the ground for Kramer to advocate a new, political identity for gay men who respond to the AIDS crisis (237). Dow shows how Kramer’s essay functions as constitutive rhetoric, helping to constitute a new identity for his audience (239-40).

Tags: Activism, HIV/AIDS, Identity

Fejes, Fred, and Kevin Petrich. “Invisibility, Homophobia, and Heterosexism: Lesbians, Gays and the Media.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 10.4 (1993): 396-422. Print.

Fejes and Petrich offer a review of literature on how scholars have approached gays, lesbians, and mass media, asking, “How do media images and meanings create definitions of homosexuality, homosexuals, and the homosexual community, and what are the consequences?” (396). They overview scholarly literature on gay and lesbian representations in film, primetime television, news media, and pornography as well as studies of audience and market analyses. They attribute the shift from pre-Stonewall invisibility to more representations of gays and lesbians in mass media to activism by gays and lesbians, but note that “[h]omophobia has been replaced by heterosexism as the major component in the mainstream media’s discourse about homosexuality and homosexuals” (412). They close by calling for further understanding of how heterosexism works, for studies of the production of media, and for reception studies of real audiences.

Tags: Heteronormativity, Homophobia, Media, Representation, Visibility

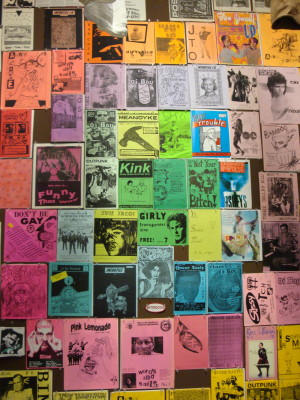

Fenster, Mark. “Queer Punk Fanzines: Identity, Community, and the Articulation of Homosexuality and Hardcore.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 17.1 (1993): 73-94. Print.

Fenster examines “homopunk” zines (independently created and distributed magazines) and the articulations and circulations of identities at the intersections of punk and queer sexualities. He argues that these zines constitute identities and communities through articulating “confrontational sexual politics” (74). These zines are situated within and against mainstream gay and lesbian communities and hardcore communities. Through analysis of published letters to these zines and the zines’ editorial content, Fenster shows how readers expressed a sense of “empowerment” through recognition in contrast to their local isolation from both gay and lesbian communities and hardcore communities (79); homocore readers and zinesters express both identification and dis-identification with hardcore and gay and lesbian scenes, often critiquing hardcore for its homophobia or lack of inclusiveness and critiquing gay and lesbian communities for their conservative politics and consumerism (81). These zines create an “intertextual community” (82) and produce identities and communities through oppositional politics and cultural practices.

Tags: Collective Identity, Identity, Media, Popular Culture

Fraiberg, Allison. “Electronic Fans, Interpretive Flames: Performative Sexualities and the Internet.” Works and Days 13.1-2 (1995): 195-207. Print.

Fraiberg situates her analysis within conceptions of the Internet in the 1990s, arguing that the Internet is not a monolithic space but rather a “segmented place” composed of a variety of spaces, and, while sex and sexuality saturate the Internet, they so in a multitude of ways (196). Fraiberg asserts that spaces devoted to sexuality already have some of the parameters of the discussion negotiated by virtue of the focus of the space (197-8). In order to explore how other online forums might be queered, Fraiberg turns to discussion lists not devoted to sexuality—one for fans of Melissa Etheridge and one for fans of the Indigo Girls—after these performers came out as lesbians (199). Fraiberg analyzes how posters’ signature files function to out them as lesbians and how the performers serve as topoi to launch broader conversations about sexuality (200-5). Discussions about sexuality in these spaces require “repeated performance, consistent reinscription,” and “textual negotiation” in ways that destabilize the space: Queer performances establish queer spaces, but they also propel discussion forward, constantly changing the space (205).

Tags: Digital, Identity, Popular Culture, Performativity

Gilder, Eric. “The Process of Political Praxis: Efforts of the Gay Community to Transform the Social Signification of AIDS.” Communication Quarterly 37.1 (1989): 27-38. Print.

Gilder examines the discursive construction of HIV/AIDS and how people with AIDS (PWAs) construct their understandings of themselves. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s analytic conceptions of bio-power and subjectification, Gilder explains that AIDS has become equated with homosexuality in the public imagination and that discourses about homosexuality have become re-medicalized (33-4). One implication of this re-medicalization is that PWAs often understand themselves, and others understand them, as “exotic but passive ‘objects’ for medical study” (28). Gilder argues that this re-medicalization has moved homosexuality from political-social realms and harmed the advancement of gay liberation. He proposes that the gay community turn to political praxis that engages in “a self-interpretive construction of AIDS” that redefines identities and AIDS and resists medicalizing discourses that objectify bodies (36).

Tags: Bodies, Collective Identity, Gay Rights, HIV/AIDS, Medical, Politics

Gross, Larry. “The Contested Closet: The Ethics and Politics of Outing.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 8.3 (1991): 352-88. Print.

Gross explores the ethics of outing by journalists and gay activists. Gross notes that the question is not one with answers on the extreme—to out everyone or to never out anyone—but rather a question of “who has the right to decide on which side of the line any particular instance [of outing] falls” (353). Gross analyzes the claims made on each side of the debate about outing throughout the twentieth century, exploring “the underlying ethical and normative assumptions” that inform these positions (354). Gross explores various tensions: journalistic traditions of protecting private life; the rise of sensational journalism; a gay history of protecting others’ secrets; a post-Stonewall gay politics of publicness; the need for visible role models for younger gays and lesbians; hypocrisy in the media for discussing heterosexual relationships but not homosexual ones; the desire to call out closeted politicians for hypocrisy when they promote antigay agendas; and, of course, an individual’s right to privacy. The rhetoric of gay activists who advocate outing, Gross summarizes, works through a “rhetoric of allegiance and accountability” that depends on an understanding of gay identity as essentialized and minoritized (379). While reactions remain strong to outing, Gross also notes that the appeals to “a narrow focus on the right to privacy” also will not work for advancing the gay movement (381).

Tags: Closet, Coming Out, Media, Politics, Privacy

Hirsch, David A. H. “De-familiarizations, De-monstrations.” Queer Rhetoric. Spec. issue of Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 13.3-4 (1992): 53-65. Print.

Hirsch argues that gay and lesbian appeals to the rhetoric of family and sympathy only serve to reinforce unjust structures and societal norms. Hirsch advocates instead for embracing antigay rhetoric that portrays homosexuals as “anti-family, because, in part, civil rights like same-sex marriage are still exclusionary and privilege the couple as family.” Hirsch argues for “constructively chang[ing] the terms of the argument” (60); gays and lesbians should see “‘monstrosity’ as a strength of difference, and not a weakness of failed similarity” (60). Hirsch closes by suggesting that rather than “stretch current definitions” of family to include a few more people (gay and lesbian couples), we should instead completely redefine the family or even disentangle the family from civil liberties completely (61-2).

Tags: Gay Rights, Heteronormativity

Johnson, E. Patrick. “SNAP! Culture: A Different Kind of ‘Reading.’” Text and Performance Quarterly 15.2 (1995): 122-42. Print.

Johnson explores the uses, functions, and ownership of the “snap,” a nonverbal communication used among African American gay men and African American women. Understanding snapping as a nonverbal form of Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s discussion of Signifying (124), Johnson explores the various meanings of its use within African American gay male communities: to “read” and to “throw shade”; snapping is often conjoined with verbal acts to punctuate verbal Signifying and can be either playful or serious (125-7). Snapping is understood as an “effeminate” act, largely associated with gayness, especially “queens” (128). It serves a community-building function, working because audience members participate through their recognition of the act (129-30). Johnson also explores appropriation of snapping by gay white men, heterosexual African American men, and heterosexual white men. Straight men often appropriate snapping through parody, Johnson notes, which serves to stereotype gay men and distance the straight performer from femininity through irony and parody (133-5). Johnson notes that many African American gay men are concerned with “ownership” of snapping, but Johnson claims that ownership is “an impossibility given the dynamics of culture” (138); however, Johnson suggests that snapping might be able to retain some of its subcultural power because of the complexity of its use and the criteria for competency that African American gay men have developed and use to judge snapping (138, 140).

Tags: Identity, Race

Malinowitz, Harriet. Textual Orientations: Lesbian and Gay Students and the Making of Discourse Communities. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1995. Print.

One of the earliest book-length projects in rhetoric and writing studies to address sexuality and pedagogy, Malinowitz explores lesbian and gay students’ risky positions in the mainstream writing class and in gay-themed writing classrooms. She discusses how lesbian and gay studies, social construction theory, and liberatory pedagogy shape her own approach to issues of sexuality in the writing classroom. Malinowitz draws heavily as well from queer theorists (such as Butler and Sedgwick) but does not talk about queer theory as a body or influence overtly. A critical concept is “assumed global validity of heterosexual knowledge” (65). This describes the ways heteronormative assumptions are social constructs generated by communities of like-minded people, and, as such, these are key to situating the positionality that LGBT people bring to the discussion of sexuality and professionalism. She describes how liberatory pedagogy takes social-epistemic rhetoric a step further and calls individuals to not only think as critical intellectuals but also to actually empower them to change the conditions of their lives. In addition to some attention on her own positionality as an out lesbian teacher in the classroom, Malinowitz spends roughly the second half of the book helping us look at the idea of a lesbian and gay-themed writing course, including her discussion of two classes at two different institutions titled “Writing about Lesbian and Gay Experience” and “Writing about Lesbian and Gay Issues,” respectively. She then walks readers through the class makeup, class texts, and class writing assignments. She shares her data as three chapters of “interpretive portraiture” that profile four students in the courses. She shares their histories, their coming out stories, and their experiences with writing in the course itself. On a final note, Malinowitz wonders, if identity is shaped by language, then how does it shape identity? (261).

Tags: Composition, Heteronormativity, Identity, Pedagogy

McLaughlin, Lisa. “Discourses of Prostitution/Discourses of Sexuality.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 8.2 (1991): 249-72. Print.

Confronting feminist claims that the representation of marginalized women in media has improved, McLaughlin argues that feminism has in fact not adequately resisted normalizing representations. McLaughlin’s primary focus is the representation of prostitutes in the media as deviant and dangerous. She overviews a history of the representation of prostitution, noting that women have historically been marked as “other” but that, due to the notion of “true womanhood,” class distinctions further marked “disreputable” women as “other” (250). Nineteenth-century representations of prostitutes were used to maintain social order and symbolize anxieties about sexuality. McLaughlin turns to contemporary television coverage of prostitutes, showing that, despite claims of improved representation, not much has changed: They are associated with moral and corporeal dangers and contrasted to images of good girls. Drawing on Foucault, McLaughlin argues that analyses along gender lines are insufficient if they do not take into account the regulatory discourses that distinguish between respectable and deviant sexual practices (256). While she admits that feminist voices have entered mainstream media, she argues that they are not necessarily heard over competing discourses and do not guarantee resistance to normalizing discourses (259-60). McLaughlin turns to the limits of identity politics in her conclusion, exploring potentials for feminist activism that may counter normalizing discourses.

Tags: Bodies, Identity, Feminism, Gender, Media, Popular Culture, Representation

Meyer, Moe. “The Signifying Invert: Camp and the Performance of Nineteenth-century Sexology.” Text and Performance Quarterly 15.4 (1995): 265-81. Print.

Understanding “Camp as a system of homosexual gestural production” (266), Meyer explores the relationship between the invention of homosexual identities in the late nineteenth century and the development of camp (a subcultural aesthetic sensibility or style of theatricality and irony). He examines nineteenth-century sexology narratives, arguing that camp, homosexual subject formation, and medical models of homosexuality are intricately linked (266). Meyer notes that the medical construction of homosexual was “a scientific response” to the visibility of subcultural cross-dressing (268-9). Medical discourses equated transvestism with homosexuality, allowing for the gender inversion theory of homosexuality; Meyer claims, “it was a pathology of fashion and gesture” (271). These medical—and after the visibility of the Oscar Wilde trial, legal—descriptions of gender inversion were then used by sodomites and inverts, who “inscribed themselves” with the descriptions of effeminacy, developing agency (275). Meyer argues that these cross-gender performances are what developed as camp, a term that was recorded only a few years after the Wilde trial (275). Thus, Meyer argues for understanding camp as “performative utterance” (275) that marked performance and recognition of homosexuals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. He closes by asking how notions of camp then changed in the mid-twentieth century, from a homosexual performative utterance to a notion of aesthetics (277-8).

Tags: Camp, Etiology, Histories, Identity, Legal, Medical, Performativity

Morrison, Margaret. “Laughing with Queers in My Eyes: Proposing ‘Queer Rhetoric(s)’ and Introducing a Queer Issue.” Queer Rhetoric. Spec. issue of Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 13.3-4 (1992): 11-36. Print.

Margaret Morrison opens this special issue of Pre/Text by calling for a “queer rhetoric(s)” that explores the intersections of bodies, desires, and language (13). Writing at a postmodern moment when she sees identity terms as increasingly unstable and “fruitfully disruptive” (12), she notes that, thus far, “lesbian and gay rhetoric” has been driven by “a normalizing impulse” (15). Drawing on Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Judith Butler, and Michel Foucault, Morrison outlines how identity categories and the homo/hetero distinction regulate bodies and attempt to (but often fail to) limit desire (15-7). Queer rhetoric, Morrison proposes, challenges the will to know one’s place or location, as in standpoint theory (19-20), and instead “suggests . . . perverse movements” (20) and the movement between veiling and unmasking (21). Morrison understands queer rhetoric as like Lynn Worsham’s reformulation of écriture feminine, a subversive and playful discourse (21-2).

Tags: Bodies, Desire, Identity

Nakayama, Thomas K. “Show/Down Time: ‘Race,’ Gender, Sexuality, and Popular Culture.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 11.2 (1994): 162-79. Print.

Nakayama analyzes the 1991 film Showdown in Little Tokyo and images in men’s magazines for representations of race, gender, and sexuality. He argues that Asians and Asian-Americans are constructed in relation to whiteness, that racial constructions are also gendered and sexualized, and that these representation serve to keep white heterosexual masculinity at the center of power. Showdown is one of many martial arts films in which “a white male typically enters Asian or Asian-American social space and emerges victorious from whatever conflict is at hand” (164). Noting a paucity of scholarly analyses that explore the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality, Nakayama turns to Showdown in order to “reverse” the impulses of feminism, race studies, and gay and lesbian studies and read instead whiteness, masculinity, and heterosexuality in the film (163). Nakayama shows how mainstream media reveals “an ideological colonialism in which white men are home everywhere” (173), Asian and Asian-American men are emasculated or hinted at being homosexual, and Asian women are sites of conquest for white men. Nakayama closes by calling for cultural studies approaches that focus on difference and take intersectional approaches.

Tags: Feminism, Gender, Identity, Media, Popular Culture, Race, Representation

Patton, Cindy. “In Vogue: The ‘Place’ of ‘Gay Theory.’” Queer Rhetoric. Spec. issue of Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 13.3-4 (1992): 151-57. Print.

Patton notes that gay readings of texts are becoming a pedagogical and critical norm, which, while erotic and pleasurable, restabilize gender binaries as natural. Patton advocates moving away from a hermeneutics of suspicion toward reading texts kinesthetically while resisting essentialism. She turns to a reading of Madonna’s music video for “Vogue” and voguing in gay clubs, exploring implications for bodies and memory. Reading “Vogue” as co-opting queer black subcultures, Patton argues, is too simple of a reading that misses the rhetoricity of voguing. The pastiche of voguing allows for a kinesthetic and cybornic performance that resists gender and racial binaries, though it also “reroutes the memory of collective resistance by queens of color” and collapses history through nostalgia (156). Ultimately, Patton argues for attending to and articulating embodied practices that might provide resistance to essentialist or binary gender, racial, and sexual identities.

Tags: Bodies, Memory, Popular Culture, Race

Perez, Tina L., and George N. Dionisopoulos. “Presidential Silence, C. Everett Koop, and the Surgeon General’s Report on AIDS.” Communication Studies 46.1-2 (1995): 18-33. Print.

Perez and Dionisopoulos examine Ronald Reagan’s prolonged silence in response to HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and analyze the 1986 Surgeon General’s Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome and the accompanying media coverage. Reagan’s silence, they contend, conflicts with modern understandings of the “rhetorical president” who responds and governs through speech in response to public concerns (18). In the context of Reagan’s silence, Attorney General Everett Koop released the Surgeon General’s Report directly to the public instead of to the President. The report’s “clinical compassion” and avoidance of moralizing (24) was praised in the mainstream media but was criticized by others in the Reagan Administration (25-6). These conflicts within the administration made Reagan’s silence on AIDS even more pronounced (27), and Perez and Dionisopoulos draw implications for understanding how silence is deployed and constrained for rhetorical presidencies.

Tags: Bodies, HIV/AIDS, Politics, Public Address, Silence

Ramirez, John. “The Chicano Homosocial Film: Mapping the Discourses of Sex and Gender in American Me.” Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 16.3-4 (1995): 260-74. Print.

John Ramirez analyzes Edward James Olmos’s American Me for its representations of gender, Chicano ethnicity, and sexuality, showing that the film serves to reinforce and support conservative family values, including patriarchy; in short, it has a “homophobic homosocial agenda” (270). The film acts as a “cautionary appeal” against the decline of the proper heteromasculinity and family, targeting gang violence, the drug trade, and homosexuality as the causes of that decline (263). American Me portrays the antagonist, Santana, as underdeveloped, emasculated, and “heterosexually-challenged” (264) and ultimately failing to fully undergo rites of passages “into the ‘legitimate’ masculine performances of capitalist enterprise, social mobility, and heterosexuality” (271). Ramirez shows how the film’s focus on failed masculinity allows it to reaffirm patriarchy and homophobia because it ultimately never challenges the logics of heteromasculinity and patriarchy.

Tags: Gender, Homophobia, Media, Popular Culture, Race, Representation

Ringer, R. Jeffrey, ed. Queer Words, Queer Images: Communication and the Construction of Homosexuality. New York: New York UP, 1994. Print

Ringer’s edited collection follows James Chesebro’s 1981 collection Gayspeak in exploring gay and lesbian communication and representations of gays and lesbians in popular culture. The collection’s goals are to provide current research on gays and lesbians from a communication studies perspective, to provide communication studies with insights from a gay and lesbian approach, and to set a research agenda for gay and lesbian communication. The collection is divided into five sections that explore gay and lesbian rhetoric, representations of gays and lesbians in mass media, constructions of homosexuality in literature and popular discourse, interpersonal communication between gays and lesbians, and coming out in the classroom. Chapters analyze and approach such topics as Harvey Milk’s political rhetoric, court cases, gay liberation rhetoric, representations in television and young adult literature, and Edmund White’s literature. As Chesebro notes in his contribution to the collection, changes in the 1980s—particularly the rise of the HIV/AIDS crisis, the introduction of postmodern theory into communication studies, and feminist insights into how no analysis is ideologically neutral—influence the arguments and analyses in this book (77-87). Analyses of representations in the media show, as Larry Gross summarizes, that while visibility was increasing in the 1980s, these representations were not necessarily positive, and, when they were intended to be positive, they often desexualized gays and lesbians to be “nonthreatening to heterosexuals” (151). The collection’s self-reflexivity is shown through responses to contributions (such as Chesebro’s and Gross’s responses) that question assumptions and ask questions about the status of gay and lesbian communication studies. Dorothy S. Painter, for example, asks questions of how gay and lesbian communication scholars justify, or should justify, studies to a broader, heterosexual field (281-2).

Tags: Coming Out, Disciplinarity, HIV/AIDS, Literature, Media, Pedagogy, Representation, Visibility

Siegel, Paul. “Are the Free Speech Rights of Heterosexuals at Risk?” Journal of Communication Inquiry. 15.1 (1991): 135-52. Print.

In the context of various universities taking action against homophobic speech in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Siegel asks if regulating hate speech is the best response. Siegel argues that this approach might clash with the values of the gay rights movement, which he understands as being predicated “at its core” on free speech (135). Overviewing a variety of legal cases, Siegel shows how the First Amendment is at the center of various gay rights arguments (135-7). Further, free speech provides benefits for society: we can argue about truth; free speech prevents hate groups from going underground, feeling victimized and becoming martyrs, and turning to violence; and it allows us to see how “lousy” we are as a society (144). Siegel’s explanation of the “‘lousy people’ rationale” suggests that we are better off responding to hate speech through rhetoric and action; silencing it is “the easy way out” (146), especially for university administrators who, by banning hate speech, do not have to actually work to counter it (147). Responding to hate speech with rhetoric also provides opportunities to advance gay rights movements (147).

Tags: Gay Rights, Homophobia

Slagle, R. Anthony. “In Defense of Queer Nation: From Identity Politics to a Politics of Difference.” Western Journal of Communication 59.2 (1995): 85-102. Print.

Noting scant research in social movements within communication studies on gays and lesbians, Slagle makes a distinction between gay and lesbian liberation movements and queer movements. Liberation movements, he explains, advocate an essentialist gay identity and seek inclusion or assimilation. Using Queer Nation as an example, Slagle shows that queer movements advocate difference from heterosexuals and within queer identity groups and argues that oppression based on difference is not justified. Slagle claims that “queer theory provides an important critique of mainstream rhetorical theory” (87) and that Queer Nation challenges identity politics by critiquing essentialized identities, challenging nationalism, and challenging the traditional public/private distinction.

Tags: Activism, Collective Identity, Gay Rights, Identity, Queer Nation

Waldrep, Shelton. “Deleuzian Bodies: Not Thinking Straight in Capitalism and Schizophrenia.” Queer Rhetoric. Spec. issue of Pre/Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 13.3-4 (1992): 137-49. Print.

Waldrep responds to Alice Jardine’s feminist critiques of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari—that their theories are abstract and move away from dealing with any “historically specific situation and struggle with women” (Polan qtd. in Waldrep 139)—by placing Deleuze and Guattari’s theory of bodies without organs in conversation with Monique Wittig’s theory of lesbian bodies. Both Wittig and Deleuze and Guattari theorize the fragmentation of the body in ways that advocate choosing one’s own desires and resisting regimes of regulation. Deleuze and Guattari, then, are “positing a new way of thinking” that involves moving beyond sexual and gendered binaries and escaping encoding of the body and desires by regulatory regimes (145). Waldrep closes by arguing that Deleuze and Guattari have practical value for radically rethinking our bodies and sexuality (145).

Tags: Bodies, Desire, Feminism, Gender, Lesbian

Section 2. Disciplinary Boundaries and Methodologies

Benson, Thomas W. “A Scandal in Academia: Sextext and CRTNET.” Western Journal of Communication 76.1 (2012): 2-16. Print.

Benson, editor of the National Communication Association listserv CRTNET in 1997, provides an account of the conversations on the listserv after the publication of Corey and Nakayama’s “Sextext.” Between January 1997 and March 1999, there were over 148 messages that directly responded to the initial thread about “Sextext” started by Robert Craig or implicitly referred to issues that arose in that thread (3). Benson situates the discourse on CRTNET about “Sextext” within broader disciplinary anxieties about “the decline of the discipline of rhetorical studies into obscurantism and Francophilia” (5). Writers on the listserv objected to “Sextext” on grounds that it was autoethnographic, amounted to pornography, or revealed the discipline’s obsession with French and postmodern theories (5). Benson also notes that writers were concerned that “Sextext” would become “a new standard” of scholarship—a claim that Benson observes “‘Sextext’ does not make for itself” (6). Benson argues that the affordances of the listserv allowed for a scholarly conversation and for readers to refute objections to “Sextext.” Additionally, the fact that Corey and Nakamura, as well as the editor of Text and Performance Quarterly, stayed out of the conversation “allowed it to go its way as a discussion among readers, and not to attain standing as a trial or deliberation” that might have harmed “editorial independence and scholarly freedom” (14).

Tags: Disciplinarity, Sextext

Corey, Frederick C., and Thomas K. Nakayama. “deathTEXT.” Western Journal of Communication 76.1 (2012): 17-23. Print.

Corey and Nakayama reflect on their 1997 essay “Sextext” fifteen years after its publication. They explore changes in communication technologies and gay male cultures and argue for new methodologies and ways of knowing for scholarship. They claim that “Sextext” did not set any new standard for scholarship as some (e.g., Craig. “Textual Harassment.” American Communication Journal 1.2 [1996]) had feared. Instead, “it merely performed a newness” (18). Changes in surveillance, exhibitionism online, chat rooms, and the migration of sexual cruising to online spaces warrant “new methodologies” because older methodologies cannot understand these new ways of being and knowing (20); however, new methodologies do not mean forgetting prior scholarship and methods but rather building off of them and creating new ways of understanding changing technologies and practices (21).

Tags: Disciplinarity, Sextext

Corey, Frederick C., and Thomas K Nakayama. “Sextext.” Text and Performance Quarterly 17.1 (1997): 58-68. Print.

Corey and Nakayuma write a “fictional account of text and body as fields of pleasure” (58) in the first-person voice of a graduate student studying masculinity, homosexual desire, and pornography. The narrator describes scenes engaging in pornography as a participant-researcher, moments of pedagogical frustration (students always doubting queer epistemologies), and his own erotic encounters with theory. Mixing academic discussions of how masculinity is idealized and desired within gay culture with erotic encounters with bodies and texts, the narration explores the difficulties of writing about homosexual desire within a heterosexual culture and within the constraints of academic discourse. This piece sparked much debate in the field on listservs (see Benson; Corey and Nakayama, “deathTEXT”; and Yep, Lovaas, and Elias’s edited collection in this bibliography).

Tags: Desire, Disciplinarity, Sextext

Fox, Catherine Olive-Marie. “Toward a Queerly Classed Analysis of Shame: Attunement to Bodies in English Studies.” College English 76.4 (2014): 337-56. Print.

English studies, Fox argues, disciplines faculty through norms and normalizing discourses, which produces shame, especially related to social class (343). As a classed endeavor wrapped up in notions of propriety and civility, the normalization of the professoriate involves the shaming of professors with working class backgrounds or who deviate from other norms of propriety. Rather than seeing shame as the opposite of pride and something to be eradicated, Fox suggests that shame also promises recognition. Drawing on queer theory, Fox sees “shame as a fundamental component of our social reality” (342), one that provides “a ‘critical opening’ that allows for integration and expansion of existing norms that govern recognition” (345). Fox provides the term “queerly classed” to describe faculty who are displaced and shamed by these normalizing discourses (340). Moments of shame, when normalizing discourses conflict with a body’s habitus, are “ruptures” that can provide openings to listen to our bodies and question norms (352). We all feel shame, Fox notes, and shame can be used to attune ourselves to “relational awareness” (353). That is, we can recognize and use shame to attend to how we are in relation with each other, developing an ethos of humility to create shared interests across differences.

Tags: Affect, Bodies, Class, Disciplinarity

Gross, Larry. “The Past and the Future of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies.” Journal of Communication 55.3 (2005): 508-28. Print.

Gross assesses the status and changes of LGBT studies and queer studies within communication studies and proposes an agenda for the future. He provides a history of LGBT studies and its development with communication studies, positioning it within an LGBT political and activist history. The 1980s were largely marked by contentions in activism and academia between those who viewed sexuality as socially constructed and those who had a more essentialist view of identity (514). In the 1990s, Queer Nation, queer theory, and people of color began to question white privilege, normative homosexuality, and essentialist sexual identities (515-517). Gross largely focuses on studies of media representation within communication studies. While he believes that suspicious readings of the media have been and continue to be useful, he claims that scholars “must move beyond surveillance and textual analysis” of the media (522). He also advocates research to further understand queer youth, the implications of queer theory’s challenges to notions of identity and sexuality, and political rhetoric (522-4).

Tags: Disciplinarity, Histories, Media, Queer Nation, Representation

Henderson, Lisa. “Queer Communication Studies.” Communication Yearbook 24. Ed. William B. Gudykunst. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2000. 465-84. Print.

Henderson assesses the state of queer communication studies, exploring the “multiple points of intellectual intervention and possibilities” in queer communication scholarship that navigates a tension between political liberation and traditional modes of inquiry (466). She stresses that queer studies is not solely the purview of LGBTQ scholars but should be of interest to all scholars because sexuality, normativity, and difference—dominant or nondominant—is “discursively organized” (468). Henderson then overviews scholarship in queer communication, also highlighting its “nonqueer relevance” (468). Henderson encourages rhetorical scholars to examine how LGBTQ people articulate their desires and identities “in relation to multiple others and multiple circumstances,” how sexual subjectivity is shaped, and how people respond to shifts in subjectivity (472) as well as questions of how marginalized sexual and gender identities are represented in the media, and how audiences respond to representations.

Tags: Disciplinarity, Identity, Media, Representation

Herring, Scott. “The Hoosier Apex.” Queering the South. Spec. issue of Southern Communication Journal 74.3 (2009): 243-51. Print.

Herring opens his essay explaining the linguistic term “Hoosier apex,” the dialect of southern Indiana that involves drawls, slow speaking, and other markers of southerness, referring to it as a “queer space” because it violates typical geographic boundaries of dialects (243-4). He proposes that the Hoosier apex can queer southern studies, questioning boundaries of the region, and that, just as scholars attend to transnationalisms, scholars, too, need to attend to interregionalisms (244-5). Herring argues that looking toward such queer spaces, which entail migrations and mobilities, is an avenue for bringing queer studies into southern studies. He shows how southern vernaculars and southern sexual cultures have migrated into the Midwest, using the southern slang “greasy” and Tina Turner as examples, exploring how interregional migrations disrupt assumed regional borders and can “enrich current theories of queer mobility, migration, and regionalism” (243).

Tags: Regionalism

Johnson, E. Patrick. “‘Quare’ Studies, or (Almost) Everything I Know about Queer Studies I Learned from my Grandmother.” Text and Performance Quarterly 21.1 (2001): 1-25. Print.

Johnson argues that queer theory gives little attention to issues of race and class and intervenes by proposing to “quare” queer studies. Drawing on black vernacular discourses, Johnson’s rearticulation of “quare” seeks to locate and articulate racialized and class-based knowledges and challenge stable identities (3). He analyzes a queer theorist’s misreading of Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied for its essentialist approaches to race and class (8-9). Johnson’s approach to quare theory also provides “a rejoinder to performativity” by attending to and theorizing material performances, agency, resistance, and historical situatedness (10). He provides an example of his approach through analyzing Marlon Riggs’s documentary Black Is . . . Black Ain’t.

Tags: Class, Disciplinarity, Identity, Performativity, Race

McAlister, Joan Faber. “Figural Materialism: Renovating Marriage through the American Family Home.” Southern Communication Journal 76.4 (2011): 279-304. Print.

McAlister argues for revitalizing the study of the figurative, or “arrangements or devices that function by ‘enhancing or altering meaning’ in discourse” (Jaskinski qtd. in McAlister 280), through exploring how subjectivity and agency are shaped by “literary, visual, and material figures” (280). Calling this approach “figural materialism,” she provides an example of such an approach through analyzing the figure of the couple. She traces the figure of the couple through various discourses, visuals, and material objects and argues that “the couple” was refigured in the 1980s and 1990s to reaffirm the normativity of heterosexual marriage. It did so, she contends, by incorporating the biggest threat to heteronormativity—eroticism—into the institution of heterosexual marriage (281).

Tags: Agency, Heteronormativity, Materiality, Visual Rhetoric

McRuer, Robert. Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability. New York: New York UP, 2006. Print.

McRuer theorizes “compulsory able-bodiedness” and its relationship to compulsory heterosexuality, showing how able-bodiedness “masquerades as a nonidentity” and is wedded to compulsory heterosexuality (1-2). Situating his argument within a critique of neoliberalism, McRuer argues that neoliberalism allows for the celebration of difference and flexible identities (2-3) but only allows for the visibility of queerness and disability temporarily, using those visibilities to shore up compulsory able-bodiedness and compulsory heterosexuality (29). McRuer’s “crip theory” is designed to expose the openings and gaps in compulsory able-bodiedness, to advocate oppositional discourses to neoliberalism, and to insist that “a disabled world is possible” (31, 71). McRuer explores various cultural sites and institutions where disability and queerness are made to appear only to then disappear in order to support domesticity, rehabilitation, and composed bodies. For composition studies, he proposes that composition is intricately connected to order and composed bodies; he advocates cripping composition, “placing queer theory and disability studies at the center of composition theory” and inaugurating “a process of ‘de-composition’” (149).

Tags: Composition, Disability, Disciplinarity, Heteronormativity, Identity, Politics

Morris, Charles E., III. “Contextual Twilight/Critical Liminality: J. M. Barrie’s Courage at St. Andrews, 1922.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 82.3 (1996): 207-27. Print.

Morris examines literary author J. M. Barrie’s 1922 graduation address at St. Andrews University for Barrie’s tactics of persona, especially liminality. Barrie, a fairly private individual, negotiated his public persona in this address through combining concealment and disclosure—particularly related to sexuality. Morris explains that the “closet” functions through secrecy that also “entices, perplexes, and teases the critic” to look for contexts that the rhetor attempts to hide but “long to be revealed” (208). Morris terms this type of criticism “critical liminality,” an approach that tacks between textual context and “‘invisible’ contexts,” or those contexts that have been silenced (208). Critical liminality requires a methodology of curiosity that seeks out these invisible contexts that can illuminate texts in new and interesting ways (221).