Transgender*: The Rhetorical Landscape of a Term

The current ubiquity of the word transgender might imply that it is an uncomplicated word.1 It circulates widely—in the media, in academia, and in the titles of organizations, archives, and resource centers—to the extent that one could argue that it is currently the most common term describing people who do not neatly align with their birth-assigned gender. Yet when we scratch just below the surface, the emergences and deployments of the term are rife with complexity and even controversy. We have written this article, a collaboration between an academic and a non-academic, to intervene in the transgender coinage narrative and to more closely attend to the ways that knowledge is built among and between academic and non-academic communities.

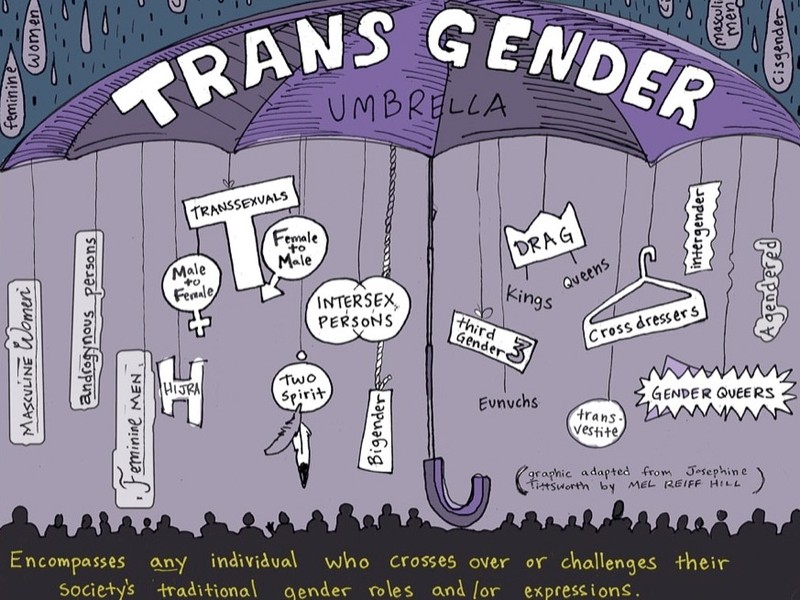

The dominant current definition of transgender relies on the metaphor of the umbrella:

Transgender: An umbrella term (adj.) for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. The term may include but is not limited to: transsexuals, cross-dressers and other gender-variant people….Transgender people may or may not decide to alter their bodies hormonally and/or surgically. (“GLAAD Media Reference Guide”)

As a spatial metaphor, the transgender umbrella may seem so capacious that we might wonder—how could a term that is this inclusive and “not limited” be contentious? Some have critiqued the “scam-brella” by arguing that transgender is a colonizing term that actually excludes transsexuals, fueling what has become known as the “trans wars” among the modern online trans community (Love). Others oppose the term for its seemingly academic slant, its perceived white bias, and its inability to account for differences among those included in the category (Valentine; Real; Namaste). Particularly for those who feel that transgender excludes transsexuals, the contention over the term is rooted in the story that is told about its historical emergence.

In academic scholarship, one particular story about the historical emergence of transgender has risen to prominence:

[Virginia] Prince coined the term “transgenderist” as a noun [in the late 1980s] to describe people who are neither transsexual nor transvestite, but instead are people who “permanently changed social gender through the public presentation of self, without recourse to genital transformation” (Stryker “(De)Subjugated” 4). In the early 1990s, Leslie Feinberg reshaped the term from a noun to an adjective in the influential pamphlet Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come and expanded the definition to include any number of people who faced gender oppression. This was the birth of the contemporary usage of “transgender” as an umbrella term. (Rawson 124–125)

As it turns out, this narrative is not only factually inaccurate, it also seriously oversimplifies the historical emergence of transgender. Two non-academic bloggers have passionately critiqued academics for rehearsing this narrative: “[This] misinformation was propagated by lazy academics who repeated the sentence in Feinberg and never bothered to fact check and search for the actual citations as they should have done. Thus we have a myth” (zagria); “Seriously, academic folks. Stop it with the ridiculous Mosaic simplicity! Please stop misrepresenting how community functions in the development [of] group identity!” (ehipassiko).2 This point of contention isn’t simply a matter of historical accuracy, but it also represents divergent ways of understanding how subcultural terminology is invented and circulated. The dominant academic narrative of transgender presumes a rather linear and hierarchical model; leaders invented a new identity term, provided it to the community, and it was uniformly embraced (with some footnoted objections). Non-academic bloggers such as zagria and ehipassiko find this to be an over-simplification of a far more complex process of language development that includes emergences, passing uses, strong resistance, re-emergences, and clustered and regional adoption. This underscores the rhetorical importance of debates about transgender—the crux of the issue isn’t merely definitional or etymological but rather the way subcultural language emerges and circulates in dynamic relationship to contextual landscapes and changing community leadership.

Our purpose in this article is to trace the contours of the rhetorical landscape of the word transgender. We are drawing the phrase “rhetorical landscape” from Gregory Clark’s recent book, in which he examines the rhetorical dimensions of space (see also Dickinson et al.). Building on Kenneth Burke’s description of rhetorical situations as “the words one is using and the nonverbal circumstances in which one is using them” (qtd. in Clark 3), Clark describes landscape as a “conceptual” term, explaining that “when landscapes are publicized—when they are shared in public discourse or in the nondiscursive form of what I am calling a public experience—they do the rhetorical work of symbolizing a common home and, thus, a common identity” (9). By using “rhetorical landscape” as a framework and method for analyzing transgender, we are shifting a more traditional etymological study into the terrain of rhetoric in order to emphasize the deeply contextual and rhetorical nature of community language development, which is particularly important for a term that constitutes a shared identity. Challenging the tidy container of the umbrella, our rhetorical landscape insists upon a more dynamic, historicized, messy, and contextualized understanding of transgender. What we offer is not a definitive and conclusive history of transgender; rather, it is a snapshot of the multi-faceted and still-continuing evolution of an important identity term in a rhetorical context.

Mapping a Landscape

One of the most obvious challenges of tracking transgender is that the combination of trans+gender is not an altogether unexpected lexical compound. Though transgender and its suffixes have prevailed in contemporary usage, the historical emergence of the term also included three important incarnations: transgenderal, transgenderist, and transgenderism.

Significantly predating the predominant academic narrative dating the term to the 1980s, the earliest known appearance of the trans+gender lexical compound can be found in the second edition of Sexual Hygiene and Pathology by psychiatrist John F. Oliven, published in 1965: “Where the compulsive urge reaches beyond female vestments, and becomes an urge for gender (‘sex’) change, transvestism becomes ‘transsexualism.’ The term is misleading; actually, ‘transgenderism’ is what is meant, because sexuality is not a major factor in primary transvestism” (514).

As a second edition, this is a particularly insightful historical artifact since the term ‘transgenderism’ was a.) completely absent from the 1955 first edition, b.) used in contrast to transsexualism in the 1965 second edition, and c.) used several times as an umbrella term inclusive of both transsexuals and crossdressers by the 1974 third edition. While these books may shed light on the medical community’s development of terminology, this is only a single thread in the complex entanglement of medical, academic, activist, and community involvement in transgender issues.

Indeed, the early 1970s saw a boom of usages of the trans+gender compound. In 1970, the term transgendered appeared in pop culture referring to a post-surgical transsexual character in an Iowa TV Guide, of all places (“Sunday Highlights”). In 1974, the term trans-gender was used as an umbrella term at the First National TV TS Conference at the University of Leeds (King). By 1975, transgenderism was used as an umbrella term in an early national trans newsletter (Mesics). This same year, the term transgenderist was featured in a trans community newspaper article titled “The Transgenderist Explained” and it described people who have two distinct yet robust personas. In 1976, the term transgenderist was used at least twice in print: in the Journal of Male Feminism and in an interview with Adriadne Kane published in Gay Community News (R. Hill 177). Kane’s 1976 use of transgenderist is particularly revealing because she explains that she uses the term to refer to a person going “beyond crossdressing to convey an image and express feelings we usually associate with femininity,” yet she is careful to point out that “none of these classifications are absolute” (“Ariadne Kane” 10). These early occurrences of the term vary widely in genre, geographic location, intended audience, and rhetorical purpose, suggesting parallel and overlapping needs for the development of language to describe existing practices in diverse contexts.

While usage of trans+gender began to gain momentum in the 1970s, this increasing momentum also brought divergent meanings of the term, which were rooted in divergent meanings of the word gender. In Oliven’s earliest use of the trans+gender compound in 1965, he distinguishes gender as something separate from sexuality and something beyond merely changing clothes. This understanding of gender resonates with a popular remark by transsexual pioneer Christine Jorgensen, who said in 1979, “If you understand trans-genders,” (the word she prefers to transsexuals), “then you understand that gender doesn’t have to do with bed partners, [sic] it has to do with identity” (qtd. in Parker). Dating back to the 1960s, those in the medical community used modifiers to clarify their use of gender. For example, Harry Benjamin, a medical practitioner who pioneered transsexual medical care, used the phrase gender role orientation in 1967 to describe Jorgensen (vii). Similarly, in 1968 Harry Gershman published a paper on gender identity, which he carefully distinguished from a person’s sex. The use of modifiers such as orientation and identity indicate that some prominent members of the medical community felt that gender needed further clarification, which likely primed the subsequent emergence of transgender.

While Oliven, Jorgensen, Benjamin, and Gershman share a common understanding of gender, there were others who viewed gender differently and therefore employed the trans+gender lexical compound in divergent ways, most notably Virginia Prince. Prince, a trailblazing activist who is often credited with coining the term transgender, used the trans+gender compound in print on two occasions during the early emergence of the term. First, in December of 1969, Prince referred to people like herself—those who do not attempt to change their sex through surgical means, but who nevertheless assumed the sex-typical costuming and conventions of the day usually associated with the opposite sex—as being transgenderal (Prince, “Change”). In his dissertation, Robert S. Hill explains that he found no further published uses of this term, or variations of it, again for almost a decade, despite the frequency of Prince’s published writing. That subsequent usage was a 1978 article where Prince used the term transgenderist to describe people who “. . . have adopted the exterior manifestations of the opposite sex on a full-time basis but without surgical intervention” (Prince, “Transcendents”). Prince was careful to distinguish gender from sex in that the former is purely cultural and the latter is purely biological. According to Hill, “Prince invented this new semantic category so as not to exclude herself and individuals like her . . . [and] to linguistically differentiate herself and her kind from transsexuals” (176).

Importantly, Prince very specifically excluded transsexuals from the terms transgenderal and transgenderist because she believed that sex was immutable: “There is absolutely no way anybody except a true physical hermaphrodite can ‘bridge the gap between male and female.’ Between man and woman or between masculinity and femininity (gender), yes, but not m and f (sex)” (Prince, ‘Letter’). Prince further asserted that while gender is changeable, transsexuals and the medical community were misguided in their attempt to address transsexualism with surgical intervention since she viewed sex as fixed (Foster). She was very careful to delineate appropriate uses of language with respect to sex and gender. For example, in 1991, she wrote, ‘female is a noun and not an adjective. If there were female and male clothing like there are female and male dogs you could breed them and get ‘baby clothes'” (Prince, “VIEWPOINT!!!”). Prince’s argument that sex is immutable seems to be the continuing basis for those who object to transgender as a term that excludes transsexuals.

While divergent understandings of gender carried into the 1980s, during this time it became increasingly common for transgender to be used as a broad and encompassing term that included anyone who transgressed the boundaries of their birth-assigned gender. For example, in 1984 a national trans magazine discussed the benefits of belonging to a “transgender community” wherein transgender was used as an umbrella term in precisely this sense (Peo). Also by 1986, a Houston, Texas group calling itself the Gulf Coast Transgender Club (GCTC) was formed, using transgender as an umbrella term (“Tau Chi”).

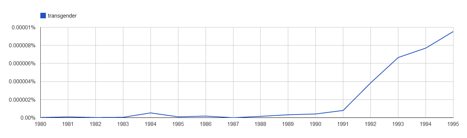

While the term was used throughout the 1980s with increasing frequency, uses of transgender really exploded in the 1990s. Though a highly imperfect tool, the Google Books Ngram viewer, which tracks word frequency in their collection of printed materials, reveals a dramatic rise of the term in print between 1991 and 1995 (Figure 2).

A few major cultural events in the 1990s likely boosted the uptake of the term: the International Conference on Transgender Law and Employment Policy (ICTLEP) was held annually from 1992–1996; in 1992, Leslie Feinberg published a popular booklet titled Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come; in 1995, the popular magazine titled TV-TS Tapestry became Transgender Tapestry; in 1996, Transgender.com was registered and featured resources for both the transsexual and crossdressing communities; and in 1997, the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association named their journal The International Journal of Transgenderism. In short, by the early 1990s transgender had risen to prominence among the trans+gender terms, and it had gained a solid foothold in both medical and activist communities.

While the term transgender was rapidly spreading in the early 1990s, Virginia Prince increasingly sought acknowledgement for coining transgender, transgenderism, and transgenderist, and she passionately fought to control how the words were being used. In a letter written to the editors of Gender Euphoria, published in a 1991 issue, Prince explains with some condescension: “I hope neither of you will take offense if grandma raises some points about your ‘transgender behavior’ article in the Sept issue of Euphoria. To begin with, I coined the term ‘transgenderist’ as a name for the specific behavior of living full time but without SRS [Sexual Reassignment Surgery]. It is a noun not an adjective” (Prince, “Letter”). Here, Prince positions herself as the singular authority on the term and strongly argues against uses of transgender that contradict her own. In another example, Prince published a 1992 article titled “Terminology for the Crossdressing Community,” where she laments the incorrect uses of transgendered and argues for a new term, “bigendered.” Tere Fredrickson published a counterpoint, arguing that transgender should be used as an “overall and inclusive term for our community,” and “suggest[ing] in the interest of standardization of terminology that the term ‘transgenderism’ as defined by Dr. Prince be abandoned by the community.” As these examples illustrate, debates about transgender terminology have often been staged very publicly and in relation to particular actors, and Prince played a central role in inciting these discussions. In part because of her activism, Prince has often been given credit for having coined the term, despite a more complex historical emergence. Yet in spite of Prince’s attempt to officially define transgender, the umbrella usage that she objected to continued to gain popularity throughout the 1990s, and by the 2000s it emerged as the dominant usage.

Conclusion

This rhetorical landscape of transgender has touched upon the earliest uses of the term, its shifting definitions, influential figures who have shaped it, notable publications that included it, debates over its meaning, and activism surrounding its continued usage. We’ve used rhetorical landscape as a method to make visible the complex historical and contextual nature of the development of community language. While the historical research we’ve offered here poses a significant challenge to the dominant academic narrative of the emergence of transgender, we are wary of establishing a new dominant narrative. Instead, we want to close with a stubborn insistence upon the continually unfolding emergence of the term transgender. The rhetorical landscape of transgender is still developing, still demanding further research, and what we have offered is just another contour in its ever-growing complexity.

Endnotes

- This article would not have been possible without the insights and efforts of a number of people and organizations including the University of Michigan special collections staff and the Transgender Foundation of America. K.J. is grateful for research support provided by the University of Kentucky. return

- To be candid, “ehipassiko” is the blogger name of Cristan Williams, co-author of this piece. return

Works Cited

- “Ariadne Kane Speaks of the Transvestites.” Gay Community News. 31 Jan. 1976: 10–11. Print.

- Benjamin, Harry. “Introduction.” Christine Jorgensen: A Personal Autobiography. Christine Jorgensen. New York: Paul S. Eriksson, 1967. Print. vii.

- Clark, Gregory. Rhetorical Landscapes in America: Variations on a Theme from Kenneth Burke. Columbia, SC: U of South Carolina P, 2004. Print.

- Dickinson, Greg, Carole Blair, and Brian L. Ott, eds. Places of Public Memory: The Rhetoric of Museums and Memorials. Tuscaloosa, AL: U of Alabama P, 2010. Print.

- ehipassiko. “Critiquing Academic ‘Coinage’ Myths: The Virginia Prince Fountainhead Myth Is Dead.” Investigate & See for Yourself. 28 May 2012. Web. 18 Sept. 2012.

- Foster, Vanessa Edwards. “Meet Virginia: Virginia Prince Visits Houston.” TATS Newsletter 7.7 (1999): 10. Print.

- Frederickson, Tere. “VIEWPOINT!!! Term ‘Bigenderal’ Correct in Reference to the Community? Counterpoint to Dr. Virginia Prince.” Gender Euphoria 6.2 (1992): 9–10. Print.

- Gershman, Harry. “The Evolution of Gender Identity.” American Journal of Psychoanalysis 28 (1968): 80–90. Print.

- “GLAAD Media Reference Guide–Transgender Glossary of Terms.” GLAAD Media Reference Guide. Updated May 2010. Web. 26 May 2012.

- Hill, Mel Reiff, and Jay Maya. [The Transgender Umbrella]. 2011. The Gender Book. Web. 30 Sept. 2013.

- Hill, Robert S. “‘As a Man I Exist; as a Woman I Live’: Heterosexual Transvestism and the Contours of Gender and Sexuality in Postwar America.” Diss. University of Michigan, 2007. Web.

- King, Dave, and Richard Ekins. “The First UK Transgender Conferences, 1974 and 1975.” Gendys Journal 39 (2007): Web. 13 Jan. 2013.

- Love, Ashley. “The Transsexual Spring: The Tide’s Shifting This Season As The Transsexual Uprising Gains Major Ground In Affirming, Accurate Education & Medical Rights.” Transforming Media. 6 May 2012. Web. 4 Oct. 2012.

- Mesics, Sandy. “Transgenderism Series.” Image Magazine (Spring 1975). Print.

- Namaste, Viviane K. Invisible Lives: The Erasure of Transsexual and Transgendered People. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2000. Print.

- Oliven, John F. Clinical Sexuality: A Manual for the Physician and the Professions. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1974. Print.

- —. Sexual Hygiene and Pathology: A Manual for the Physician. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1955. Print.

- —. Sexual Hygiene and Pathology: A Manual for the Physician and the Professions. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1965. Print.

- Parker, Jerry. “Christine Recalls Life As Boy From the Bronx.” Winnipeg Free Press. 18 Oct. 1979: 27. Print.

- Peo, Roger E. “The ‘Origins’ and ‘Cures’ for Transgender Behavior.” The TV-TS Tapestry 42 (1984): 40–41. Print.

- Prince, Virginia. “Change of Sex or Gender.” Transvestia 10.60 (Dec. 1969): 53–65. Print.

- —. “Letter.” Gender Euphoria 1 Sept. 1991: 7–9. Print.

- —. “The ‘Transcendents’’or ‘Trans’ People.” Transvestia 16.95 (1978): 81–92. Print.

- —. “VIEWPOINT!!! Bigenderal Introduction: Terminology for the Crossdressing Community.” Gender Euphoria 6.2 (1992): 9–10. Print.

- Rawson, K.J. “Accessing Transgender // Desiring Queer(er?) Archival Logics.” Archivaria 68 (Fall 2009): 123-140. Print.

- Real, Julian. “Ten Thoughts on the Current Conflicts Between RadFem and Transgender Activists.” 3 June 2012. Web. 13 Jan. 2013.

- Stryker, Susan. “(De)Subjugated Knowledges: An Introduction to Transgender Studies.” The Transgender Studies Reader. Eds. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, 2006. 1-17. Print.

- “Sunday Highlights.” TV Guide. 26 Apr. 1970: 15. Print.

- “Tau Chi–Who We Are.” Nd. Web. 19 Feb. 2013.

- “The Transgenderist Explained.” FI News 6 (1975): 4–5. Print.

- Valentine, David. Imagining Transgender: An Ethnography of a Category. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2007. Print.

- zagria. “TG, word and concepts: Part 4: The Myth that Transgender is a Princian Concept.” A Gender Variance Who’s Who: Essays on Trans, Intersex, Cis and Other Persons and Topics from a Trans Perspective……. All Human Life is Here. 22 Sept. 2011. Web. 26 May 2012.

K.J. Rawson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at the College of the Holy Cross. At the intersections of queer, feminist, and rhetorical studies, his scholarship focuses on the rhetorical dimensions of queer and transgender archiving in both traditional and digital collections. With Eileen E. Schell, he co-edited Rhetorica in Motion: Feminist Rhetorical Methods and Methodologies (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010) and his scholarship has also appeared in Archivaria, Enculturation, and several edited collections. He recently began work on the Digital Transgender Archive, an online database and digital repository of transgender-related historical materials.

K.J. Rawson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at the College of the Holy Cross. At the intersections of queer, feminist, and rhetorical studies, his scholarship focuses on the rhetorical dimensions of queer and transgender archiving in both traditional and digital collections. With Eileen E. Schell, he co-edited Rhetorica in Motion: Feminist Rhetorical Methods and Methodologies (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010) and his scholarship has also appeared in Archivaria, Enculturation, and several edited collections. He recently began work on the Digital Transgender Archive, an online database and digital repository of transgender-related historical materials.  Cristan Williams is a trans historian and advocate for addressing the practical needs of the transgender community. She pioneered numerous transgender social service, homeless and health programs, founded the Transgender Center, Transgender Archive and is the editor at the social justice site the TransAdvocate.com. She co-chairs the City of Houston HIV Prevention Planning Group, is the jurisdictional representative to the Urban Coalition for HIV/AIDS Prevention Services (UCHAPS), serves on the national steering body for UCHAPS and is the Executive Director of the Transgender Foundation of America.

Cristan Williams is a trans historian and advocate for addressing the practical needs of the transgender community. She pioneered numerous transgender social service, homeless and health programs, founded the Transgender Center, Transgender Archive and is the editor at the social justice site the TransAdvocate.com. She co-chairs the City of Houston HIV Prevention Planning Group, is the jurisdictional representative to the Urban Coalition for HIV/AIDS Prevention Services (UCHAPS), serves on the national steering body for UCHAPS and is the Executive Director of the Transgender Foundation of America.