Isocratean Citizenship in the Making of Market Citizens

While teachers of rhetoric have been tasked with producing a particular kind of student-as-citizen since Greek and Roman antiquity, there is a growing body of composition scholarship arguing that teachers of college writing need to more strongly interrogate a received model of citizenship predicated on economic productivity. Bruce Horner, Nancy Welch, and Tony Scott, among many others, have stressed the extent to which the conditions of composition, for both instructors and students, are already determined by neoliberal market forces. Neoliberalism, defined by Scott as “the embedded commonsense principle that most spheres of human life are better perceived, managed, and evaluated as markets” has thoroughly suffused academe, even though many within the university deplore this (14). One consequence of such pervasive neoliberal logic has been that public institutions of higher education, whose budgets depend on political contingencies, have increasingly justified their course offerings in economic terms, representing themselves as sites of economic production. When certain university offices—including administrators, marketers, and others—accede to representations of higher education as an engine of the market, they require students to behave individualistically and competitively in the classroom, that is, to behave a market-oriented citizenship. Composition scholarship on the neoliberal university makes clear that faculty do not always surrender to such directives; the resulting tension can become a site for educative exploration.

Pedagogical intervention can help instructors of college writing to resist narrowly economic conceptions of citizenship, and I propose that reconceiving key citizenship notions of publicity and community through an Isocratean model can counteract these limited, economic rationales for education. Economic citizenship in which “a good citizen is an earner” needs interrogation because a society that privileges it above other forms of citizenship views its citizens in an extremely limited way (Sklar, qtd. in Wan 165). Economic citizenship measures citizens as individuals, by their singular contributions to the economic wealth of the nation. Alternatively, Isocratean notions of citizenship allow us to focus on a collective citizenry whose aims are not necessarily capitalistic. While focusing on individuals produces a form of citizenship congruent with the conception of economic citizenship universities are being asked to offer, an Isocratean collective citizenry can challenge that mode to offer instead a classroom where students can learn to construct themselves as citizens through rhetorical action, sidestepping the competitiveness the market requires. To demonstrate the possibility of an Isocratean approach to citizenship in the classroom, I first examine the post-2008 emphasis on the market value of college education, and the student behavior it calls for. I then detail how an Isocratean conception of citizenship as constituted through discourse provides an alternative to this economic model.

Market Logics of the Post-2008 Era

Economic concerns have consistently featured in American rationales for education for some time. Norton Grubb and Marvin Lazerson trace what they call “vocationalism”: “an educational system whose purposes are dominated by preparation for economic roles” to the late 19th century (3). Nevertheless, as Grubb and Lazerson acknowledge, the age of austerity following the 2008 financial crisis has given these impulses new vigor. Amy Wan attributes economic conceptions of student value to even earlier than the financial crisis, tracing them in part to the 2006 Department of Education report A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of U.S. Higher Education, which provides “a model of citizenship [ . . . ] inextricably linked at the individual level to both education and productivity,” viewing college students as “America’s most valued economic asset” (151, 152). The result, Wan writes, is “the subsequent deemphasis on the aspects of cultural citizenship that do not have an immediate economic payoff” (154).

The push for curricula with increased vocational focus found in post-2008 political rhetoric can be understood as a public manifestation of the neoliberal framework motivating education. In the political sphere, for example, in February 2015, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker released his annual budget proposal, which sought changes to the University of Wisconsin’s mission statement. These included dropping the sentence, “Basic to every purpose of the system is the search for truth,” and adding the (italicized) phrase, “The mission of the system is to develop human resources to meet the state’s workforce needs” (Qtd. in Bump, emphasis added). This rhetoric reveals its expectation of the economic role UW students will fill for their state. Another notable instance of this argument is found in then-presidential candidate Senator Marco Rubio’s November 2015 argument against “stigmatized vocational training,” claiming that “Welders make more money than philosophers. We need more welders and less philosophers” (Qtd. in Youngman). Rubio’s argument understands the value of welders, as opposed to philosophers, to be primarily economic. These statements of value are not only offered by America’s ideological right; former President Barack Obama’s 2010 plan to provide free community college claimed, “In an increasingly competitive world economy, America’s economic strength depends upon the education and skills of its workers” (“Building American Skills”). Rather than making an argument for community college as a public good, the Obama administration argued from the assumption that increased education would lead to increased economic productivity.

In the field of rhetoric and composition, even scholars who might otherwise be negatively disposed to some of the logic displayed in these comments still buy into economic rationales for education in subtle ways. Linda Adler-Kassner, for example, has written critically of the “college- and career-readiness agenda,” offering instead a pedagogy grounded in “communities of practice”—“physical or imagined locations” that are “bound together [ . . . ] by shared rituals, practices, and commitments” (450). I agree with this aim, which bears resemblance to the practice of collective citizenship I call for in this essay. However, I disagree with the way that Adler-Kassner rationalizes the claim, arguing that we can “reclaim the term college ready and create or highlight approaches that demonstrate how a remodeled balance between liberal learning, professional training, and disciplinary identity can help students become career ready” (449). Adler-Kassner’s move—to rationalize a good pedagogical tactic in troublesome economic terms—is sadly not an aberration. Even a foundational document like the CCCC Statement on Students’ Right to Their Own Language, written in 1974 and reaffirmed as recently as 2014, states that “English teachers should be concerned with the employability as well as the linguistic performance of their students.” Again, an admirable goal becomes yoked to a market rationale. The political calls for economically grounded education matter to teachers of composition because they influence why the students arriving in their classes are attending college, as well as assumptions and expectations about how they should behave as students in the neoliberal university. And compositionists’ responses, accepting market rationalizations even while offering critique, matter to students because they reinforce the influence that the political discourse around education has over them. Students hear enough about the need for education solely to find jobs without their teachers reinforcing it back to them, as well. If composition teachers wish to offer their students reasons for education other than mere return value, they must challenge students to behave differently from how the market asks them to.

Conceptions of citizenship predicated on economic output ask students to behave in classes in individualistic and competitive ways; such behaviors reinforce students’ understandings of their identities primarily using market ideals. As Jeffrey Gross has noted, under the neoliberal framework, when people “must work to enhance their value, public education becomes a site for competition rather than a common good.” Thus, neoliberal framings of education for economic citizenship encourage students to “compete” with each other for grades. Neoliberal framings also undermine student investment in graded group projects, in which their success is bound up in others’, because such projects make it harder to compete individually, for example.1 Current first-year college students have typically completed more than half their educational careers under the post-2008 neoliberal model, so it is no surprise that competitive economic terms powerfully shape how they understand their schooling. Student behavior changes as a result of this understanding, so the effect of measuring individual value capitalistically is, as Kenneth Burke argued, a kind of imitation, in which “the so-called ways of competition have been almost fanatically zealous ways of conformity” (131). Burke goes on to claim that “from the standpoint of ‘identification’ what we call ‘competition’ is better described as men’s attempt to out-imitate one another” (131). I believe that the homogenization of behavior that results from competition can be seen in writing classrooms when students are often hesitant to make strong claims in essays that might separate them from their peers or be found “wrong,” and when they express a desire for testable knowledge, something more solid than the ambiguity of writing.

We can challenge this devaluing of non-marketable forms of citizenship by asking students to behave differently in the classrooms, de-centering the economic motive. Market value is not the only way that citizenship can be constituted, even if it is currently our defining mode. An alternative would be a notion of citizenship as “a collective practice, one that relies on the relationships among citizens” (Wan 177). This notion of citizenship has much in common with classical understandings of the term. Reinvesting our teaching practices in an Isocratean notion of citizenship offers such an approach, which is radically different from our current individualistic and economic emphasis.

Efficacy, Publicity and Isocratean Community

Isocratean rhetorical theory offers a framework for implementing a constitutive discourse of citizenship, one based on collectivity, rather than competitive individualism.2 For Isocrates, rhetoric plays an essential role not just in determining how different members of a community interact with one another, but also in forming the community itself. In his speech Nicocles,3 Isocrates claims that “there is no institution devised by man which the power of speech has not helped us to establish,” and as a result, “we have come together and founded cities and made laws and invented arts” (6). Because speech has the power to establish institutions, it is a necessary condition for community. According to Isocrates, speech “has laid down laws concerning things just and unjust, and things base and honorable; and if it were not for these ordinances we should not be able to live with one another” (7). The action that enables this conjoined living is not one that citizens take using speech, but one that speech itself takes. Constituting citizenship (here the creation of cities or the establishment of laws) is part of a broader process of self-conception; Takis Poulakos writes that for Isocrates, it should be understood as “neither action nor eventfulness but rather a self-understanding, a way of constructing oneself and of relating to one another in the city” (21). Thus, “logos guides by promoting a particular self-understanding and by eliciting audiences to understand themselves in ways that make collective participation and deliberation seem possible and desirable” (Poulakos 21). By understanding rhetoric as having the power to establish societal institutions, students can enact Isocratean citizenship by rhetorically constructing a community in which they are efficacious actors. This is similar to but distinct from the notion of “discourse communities” as frequently discussed in composition literature, because instead of aiming to use speech to join existing communities, students speak (or write) to constitute them.

It is important for students to constitute citizenship communities because doing so fosters their efficacy. Traditionally, one of the most vexing problems in attempting student civic engagement is the limited efficacy of their actions (McMillan 191). This problem can be addressed if students, following Isocrates, construct a community in which their own rhetorical authority matters. Brian Gogan offers a framework for this construction, using the metrics of publicity, authenticity, and efficacy.4 Gogan uses these metrics to “emphasize the non-persuasive effects of public rhetoric as well as the persuasive ones,” viewing all of a student’s public-oriented actions as “participation in the ecology” of a community (551). Viewing Gogan’s metrics through Isocratean notions rhetorically constituted publics helps illuminate their effectiveness in a classroom. Jill McMillan, who argues that students learn democracy by practicing it, cites Paulo Freire’s idea that dialogue “should be a cocreation of educator and educatee” (191). Isocrates’ sense of the power of logos to construct our society—in Freire’s words, to “name the world,” (Qtd. in McMillan 191)—is useful, here, as is the notion of logos as a joint practice between rhetors and their community. Moreover, using Gogan’s framework of publicity-as-action allows this process to be taught, because “understood as an activity, pedagogy assumes the power to authorize publicness” (539).5 The pedagogical intervention I am advocating, based on an Isocratean model of constitutive community citizenship, applies Gogan’s ideas not only to students’ public writing but also to their self-conception and their everyday practices in writing classrooms, allowing students to understand themselves not as competitive individuals, but members of a collective, whose motivations are not solely economic. This could mean asking students to collaboratively interpret course outcomes into a guiding “constitution” which espouses community values by which they can all work. It could also involve asking students to collaboratively compose ethos statements articulating who they want to be as a community, and whose efficacy will be evaluated the participation it generates.

Valuing participation allows us to follow Gogan’s understanding of rhetorical efficacy as “predicated first on participation,” meaning that a student’s public rhetorical ability is not a measure of whether or not they can leave the institution to enter the public (550). This is a narrow construction of publicity that is too often pursued: publicity that requires sending students away from the classroom to engage with the “community.” It fails by repeating the old (and spurious) dichotomy between the university and the “real world,” but it also suggests that writing done in and for class situations has less value because it is not public.6 Instead, the rhetorical construction of a public allows students to write for situations with which they are already familiar, which in turn fosters their efficacy. When students feel able to participate, and understand their actions using an Isocratean model of constitutive citizenship, they can behave in different ways than just competitively. The goal of this model is to foster genuinely collaborative actions in the classroom.

Conclusion: Constituting Collectivity

Entering a rhetorical community as a participant is a successful application of the goal of Isocratean imitation, a creative process where students practice by “learning how to speak in the many distinctive voices that make up the city as a whole” (Hariman 230). This insight is valuable for its emphasis on collectivity; students are not speaking in many voices, each possessed by individuals, as in expressivism, but in voices that comprise an entire community, one whose goals can be shared among members. Robert Hariman argues that in Isocratean rhetoric:

“The logos politikos is not a single code or original text, but a creative process through which many speakers and audiences collaborate to invent ever more eloquent statements of who they are and what they should do. More important, no one speaker can speak the logos politikos. It is the voice of the city: polyglot, multifaceted, and openly adaptive to a myriad of new circumstances.” (225)

Isocratean public discourse is the voice and discussion of a collective citizenry, and thus in order to use it, rhetors must work to act fluidly in the discourses of many groups and situations. This makes this concept broadly applicable to different educational contexts, but importantly, it also forecloses using the limited economic form of citizenship as a sole mode of behavior. Instead, it requires students to use their writing to more fully articulate their many selves, understood collectively. Consequently, composition classrooms that take their commitment to civic education seriously must provide students with practice constructing communities in their writing, with the goal of becoming participants. Other recent scholarship in composition has begun to take up this idea through different traditions, as well, like employing religious rhetorics alongside epideictic (DePalma) or using decolonial methods in work with indigenous communities (Jackson). I hope that additional scholarship can further develop these ideas, especially as related to classroom practice.

As students build connections between the communities they constitute, they can understand the concept of relational citizenship. These methods attempt a reorientation of our primarily economic view of American civic life toward a more collective practice, one with classical precedent. This especially matters in a time when public discourses about citizenship and education have become so dysfunctional; the rhetoric of collective citizenship helps students develop skills that may shift away from contention, and toward a re-understanding of education as a common good. Composition classrooms can then become a site where collective citizenship is engaged in, and where dubious desires for marketable skills are productively resisted. By modeling collective citizenship and emphasizing the efficacious student construction of civic identity and community, the classroom can both value and refigure citizenship away from its market fixation.

Endnotes

- Hephzibah Roskelly attributes confusion about the purpose of group work to the conflicting assumptions and motivations underlying its use: “group work so often fails [because] the practice of using groups conflicts with theories about knowledge and achievement that teachers, students, and institutions hold on to, mostly unconsciously. How can a student be simultaneously collaborative and competitive with others?” (5). return

- While it is true that the economics of ancient Greek rhetoric favored, as they do still, the wealthy elite, it is still possible to find valuable concepts from this body of work that may be employed toward more egalitarian ends; that is my aim in this essay. return

- Nicocles, and its counterpart To Nicocles, have been seized upon by Isocrates’ critics as proof that he had little concern for democratic values. Nicocles was a young king of Cyprus, and Isocrates made these speeches to advise him on “how to lead his people and what to expect of them” (Poulakos 26). Poulakos argues that Isocrates’ advice largely depends on Nicocles’ ability to “speak like a citizen”—his construction of rhetorical authority—because “the words of a leader are as authoritative as is the text produced” (26). return

- Gogan defines these further: publicity is “the degree to which a composition is accessible, visible, or audible;” authenticity is “the degree to which a composition is real, significant, or tangible;” and efficacy is “the degree to which a composition is capable of changing the status quo, impacting decisions, or spurring actions” (537). Furthermore, each of these categories can be taught in two ways: publicity as condition and action, authenticity as location and legitimation, and efficacy as persuasion and participation (538). return

- By this, Gogan means that “publicity signifies the process by which a rhetor seeks, engages and widens the attention of publics,” and that “that activity can be guided through pedagogical instruction” (539). return

- See Gogan 543-544. return

Works Cited

- Adler-Kassner, Linda. “Liberal Learning, Professional Training, and Disciplinarity in the Age of Educational “Reform”: Remodeling General Education.” College English, vol. 76, no. 5, 2014, pp. 436-457.

- “Building American Skills Through Community Colleges.” The Obama White House, obamawhitehouse.archives.gov.

- Bump, Philip. “Scott Walker Moved to Drop ‘Search for Truth’ from the University of Wisconsin Mission. His Office Claims it was an Error.” The Washington Post, 4 Feb. 2015, www.washingtonpost.com.

- Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. U of California P, 1969.

- CCCC. “Students’ Right to Their Own Language.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 25, 1974 (Reaffirmed November 2014), cccc.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/srtolsummary.

- DePalma, Michael-John. “Reimagining Rhetorical Education: Fostering Writers’ Civic Capacities through Engagement with Religious Rhetorics.” College English, vol. 79, no. 3, 2017, pp. 251-275.

- Gogan, Brian. “Expanding the Aims of Public Rhetoric and Writing Pedagogy: Writing Letters to Editors.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 65, no. 4, 2014, pp. 534-559.

- Gross, Jeffrey. “The Racial Veil: Small Government Rhetoric, Neoliberalism, and School Resegregation.” Present Tense, vol. 6, no. 2, 2017.

- Grubb, W. Norman, and Marvin Lazerson. The Education Gospel: The Economic Power of Schooling. Harvard UP, 2004.

- Hariman, Robert. “Civic Education, Classical Imitation, and Democratic Polity.” Isocrates and Civic Education, edited by Takis Poulakos and David Depew, U of Texas P, 2004, pp. 217-234.

- Isocrates. Nicocles or the Cyprians. Edited by George Norlin, Perseus Digital Library, 21 May 2018, www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- Jackson, Rachel C. “Resisting Relocation: Placing Leadership on Decolonized Indigenous Landscapes.” College English, vol. 79, no. 5, 2017, pp. 495-511.

- McMillan, Jill J. “The Potential for Civic Learning in Higher Education: ‘Teaching Democracy by Being Democratic.’” The Southern Communication Journal, vol. 69, no. 3, 2004, pp. 188-205.

- Poulakos, Takis. Speaking for the Polis: Isocrates’ Rhetorical Education. U of South Carolina P, 1997.

- Roskelly, Hephzibah. Breaking (into) the Circle. Boynton/Cook, 2003.

- Scott, Tony. “Subverting Crisis in the Political Economy of Composition.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 68, no. 1, 2016, pp. 10-37.

- Wan, Amy J. Producing Good Citizens: Literacy Training in Anxious Times. Pittsburgh UP, 2014.

- Youngman, Clayton. “Marco Rubio Said Wrongly that Welders Make More Money than Philosophers.” PolitiFact, 11 Nov. 2015, www.politifact.org.

KEYWORDS: citizenship, Isocrates, marketplace, classical-rhetoric, public

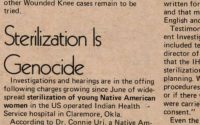

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: Isaiah Cox, https://www.flickr.com/photos/118809695@N05/24490918612

Carl Schlachte is a Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, specializing in rhetoric and composition. His dissertation, “Before the Aftermath: A Pedagogy for Disaster Responsiveness,” investigates how teachers of college writing respond in the moment to social, natural, and political disasters. His work is forthcoming in the edited collection The Things We Carry: Strategies for Recognizing and Negotiating Emotional Labor in Writing Program Administration.

Carl Schlachte is a Ph.D. candidate in English at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, specializing in rhetoric and composition. His dissertation, “Before the Aftermath: A Pedagogy for Disaster Responsiveness,” investigates how teachers of college writing respond in the moment to social, natural, and political disasters. His work is forthcoming in the edited collection The Things We Carry: Strategies for Recognizing and Negotiating Emotional Labor in Writing Program Administration.