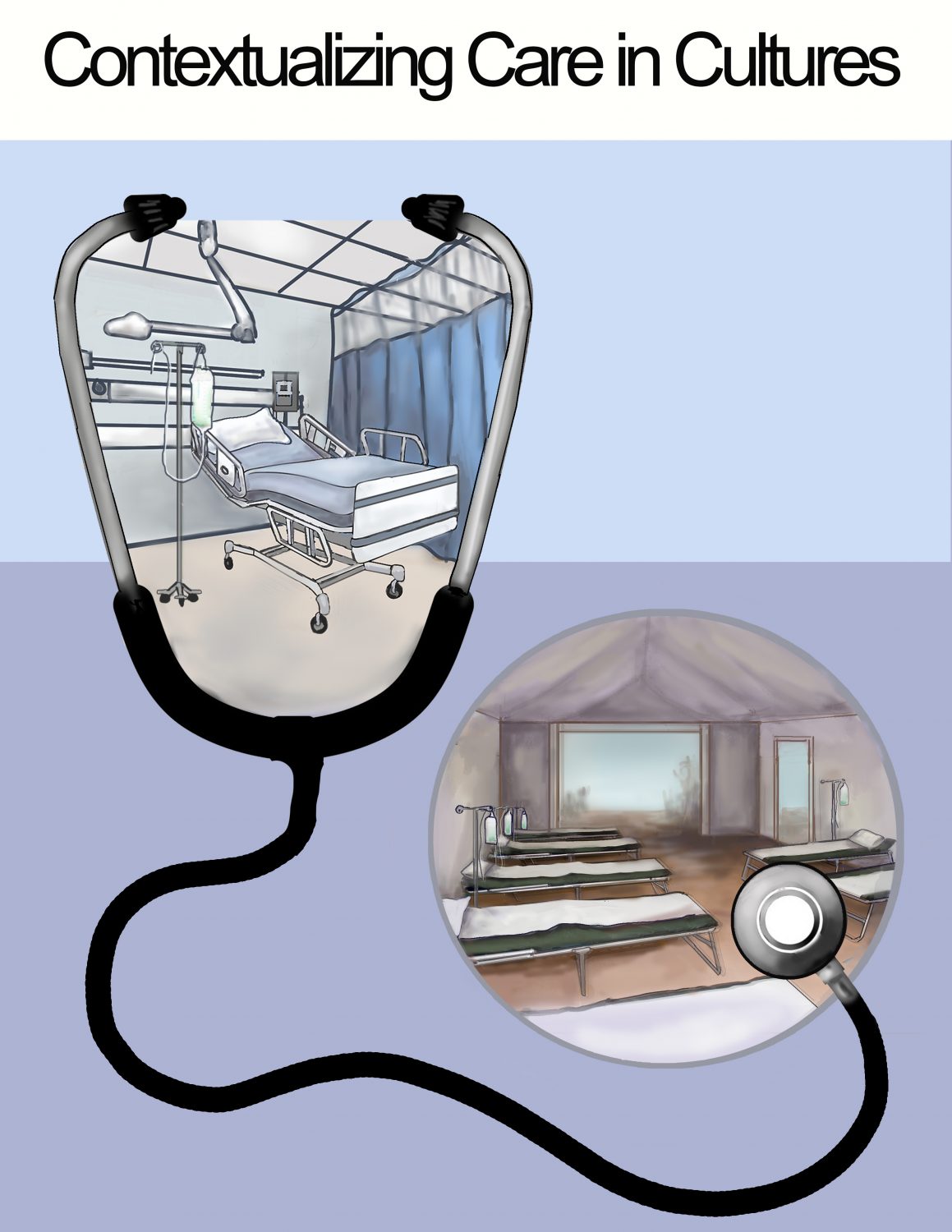

Contextualizing Care in Cultures: Perspectives on Cross-Cultural and International Health and Medical Communication

The nature of society means health and medical communication often occurs in different international and local settings (Napier et al. 4–5). Such interactions generally involve offering care—practices that help individuals maintain or return to a level of health and wellness (Braveman 182; Sartouris 662–3). These exchanges usually take place in different cultural, linguistic, and geopolitical environments involving individuals who:

- Provide care to others

- Educate others on care and caregiving

- Receive or participate in such care

In these situations, care-related information must be contextualized to address how care is perceived and administered in such contexts (Melonçon 19–20; St.Amant, “The Cultural Context” 64). Doing so is not easy, for it requires an understanding of the cultural context of care. In this special issue, the authors examine a range of contexts of care to show how technical communicators and rhetoricians of health and medicine can work at the intersections of health, wellness, and culture to contribute to healthcare practice.

Cultural Contexts of Care

The context of care is the setting where individuals provide or receive care (Melonçon 19–20, St.Amant, “The Cultural Context” 64). These contexts are shaped by the cultures where processes occur (Thomas). Understanding such environments involves addressing variables of care–factors affecting how care is provided in a society (St.Amant, “The Cultural Context” 63–64). Identifying such variables is not easy. However, technical communicators and rhetoricians of health and medicine can do so by asking a series of questions, all of which the authors explore in this special issue. The entries here offer readers models for studying different cultural contexts of care. All of these articles address each question in their own way, yet some authors address certain questions more directly than others.

Question 1: When is Care Administered?

Access to care is essential, yet, when individuals can access care varies from culture to culture (Access to Care). The schedules by which societies operate often dictate when individuals can receive care or perform care-related activities on themselves (St.Amant, “The Cultural Context” 64–65). These factors involve everything from timing of individual healthcare meetings to the frequency of treatments over time. They also encompass when individuals can access certain technologies (e.g., dialysis machines) or resources (e.g., medications) essential to caregiving. Factors to identify include:

- When healthcare facilities are open for individuals to access care

- When individuals should receive care (e.g., treating one’s self vs. going to a medical facility)

- When healthcare providers are available to provide care

- When different tools and technologies are available to use in caregiving

- When individuals can access healthcare providers or facilities based on their life schedules

Thus, the “when” variable affects the cultural schedule of care, or how cultures perceive the timing of care-related activities.

A schedule of care can encompass events that happened decades before the onset of a medical issue. Hopton and Walton’s entry details how, when, and where the Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange (VAVA) administers care to victims of Agent Orange, a toxic chemical agent used during the Vietnam War. Their article reveals how the context of care can extend beyond both physical space and the dynamics of here-and-now. Rather, technical communicators and rhetoricians of health and medicine need to avoid focusing exclusively on time-bound contexts of care. They instead need to consider how past events, current developments, and future needs can influence what is essential to effective care.

Jennings continues this focus on how past contexts of care influence present-day practices. In her entry, she discusses methods for re-examining care-related policies in different post-colonial contexts. Doing so is important to understanding (and avoiding) practices that can affect or marginalize the traditions and values of other cultures. As such, both Hopton and Walton, and Jennings show readers how this “when” factor can dictate where care is offered.

Question 2: Where is Care Administered?

The “where” variable also involves access (Thomas 103–4). It encompasses the places the members of a culture can go to receive care (St.Amant, “The Cultural Context” 64). Sometimes, this variable involves financial constraints: National healthcare policy might restrict the resources individuals can access or the places they can go to “buy access to care.” Alternatively, it could be geographical, with care facilities located in limited places in a nation.

The “where” factor also involves if individuals must visit a particular place to receive care or if care is provided in the contexts of the individual’s home (St.Amant, “The Cultural Context” 65–66). As such, it encompasses the care available based on the materials in a location. Medical facilities, for example, often have more care-related tools and technologies than someone’s home. This means the care available in one environment could differ from that of another. Likewise, different facilities might offer access to different care providers (e.g., specialists) and overall numbers of care providers (e.g., nursing staff working with physicians).

Flores-Hutson et al. examine how issues of language and culture require a re-thinking of health literacy activities in different locations. They provide a model for how care extends into communities and how literacy initiatives promote healthy eating. These dynamics lead to the next question: Who may provide care and be seen as a “recognized” provider?

Question 3: Who May Provide Care?

The perceived legitimacy of caregiving activities often connects to who provides care in a context (Gardner-Roberts). Cultures, however, can have varying perspectives of who—according to societal norms—may legitimately administer care. Cultural norms might dictate only certain individuals can administer caregiving activities. This perspective affects who the members of a culture allow to perform caregiving activities on them. It can also affect access to care if cultures have legal restrictions that penalize “non-recognized” individuals who administer care or national policies that do not cover costs associated with care from “non-recognized” providers.

In her article, Wang overviews how cultural and historical factors should be considered in reviewing perceptions of and approaches to care in specific cultural contexts (i.e., China). Focusing on the role of the yuesao, a Chinese postpartum care provider, Wang explores the boundaries drawn between biomedicine and Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) by European and North American healthcare professionals and commentators. In doing so, Wang helps us consider another questionof what care is and what constitutes a legitimate caregiving activity in different contexts.

Question 4: What Constitutes Care?

Cultures do not always agree on what activities constitute legitimate care (Improving Cultural Competence 2, 12). Consider how differences in perceptions of “homeopathic” or “folk” treatments vs. allopathic medicine can vary across cultures. Accepted practices in traditional Chinese medicine (e.g., acupuncture) might be a standard part of care in the People’s Republic of China. In the US, however, they are usually viewed with skepticism and often not covered by health insurance. Such differences restrict who can legitimately provide care in a culture. They also influence what can be used in caregiving activities.

Such variations can encompass if, when, and how individuals engage in care-related activities (Grissinger 471; Horne et al. 1307–8). If the members of a culture view care as something others provide, they might be skeptical that lifestyle choices constitute care and affect one’s health. Dietary choices, sedentary lifestyles, and the uses of different substances (e.g., tobacco) might not be considered part of a patient-initiated caregiving process associated with one’s overall health and wellness. Accordingly, attempts to convey such factors in terms of health and care might be dismissed or not recognized by certain individuals.

Such factors can be seen in uses of visuals vs. text to convey concepts of health, medicine, and care. For example, one way to convey healthcare and treatment is through visuals, and Bloom-Pojar and DeVasto’s article highlights the critical role of visuals in contexts of care. Using the Zika virus, they illustrate how translingual contexts impact our understanding of care. In so doing, they extend these ideas to examine uses of visuals when localizing materials for different audiences. These situations also touch upon a final question to ask about caregiving activities.

Question 5: What Can be Used to Administer Care?

What constitutes a valid implement for administering care can vary culturally (Grissinger 471; St.Amant, “Culture and the Contextualization” 44). Sometimes, it involves what medicine individuals will ingest or apply to address a health-related condition (e.g., traditional herbal treatments vs. sanctioned pharmacological products). Alternatively, it can involve the preferred or expected form of medicines (e.g., as an extract ingested via pill). It can also encompass the devices used to monitor vitals (e.g., a Pinard’s cup vs. a stethoscope) or diagnose conditions (e.g., using a tuning fork vs. an X-ray machine to identify broken bones).

In his article, Archaya examines such ideas by providing a method for researching usability on devices in different cultural contexts of care. Specifically, he examines how effectively medical practitioners in emerging economies can use health and medical devices developed in industrialized nations. Through such examinations,he helps us consider how these aspects represent part of the dynamics affecting care in international and intercultural contexts.

It is through the approaches described here that this special issue explores these central concepts and connections of context, culture, and care.

Final Thoughts

The better we understand the interrelated dynamics of context, culture, and healthcare, the better we can create materials that allow different cultures to engage in successful caregiving activities. Gaining such understanding involves researching the contexts in which cultures engage in caregiving activities and with caregiving materials (St.Amant, “The Cultural Context” 64–67; St.Amant, “Culture and the Contextualization” 43-45). This special issue presents six entries that examine core aspects of context and culture relating to care. Collectively, these entries provide different approaches for examining various cultural contexts of care. As such, these articles provide a foundation upon which others can build to further examine this overall area of research. By advancing our understanding of such topics, we can increase the quality of care offered to and in different cultures.

This issue contains the following articles:

Works Cited

- “Access to care.” Country Health Rankings & Roadmap, 2 July 2019, https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/measures-data-sources/county-health-rankings-model/health-factors/clinical-care/access-to-care.

- Braveman, Paula A. “Monitoring Equity in Health and Healthcare: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, vol. 21, no. 3, 2003, pp. 181–92.

- Gardener-Roberts, Sophie. “11 things you need to know about French pharmacies.” Complete France, 2 July 2019, https://www.completefrance.com/living-in-france/healthcare/11-things-you-need-to-know-about-french-pharmacies-1-5148234.

- Grissinger, Matthew. “Cultural Diversity and Medication Safety.” P&T, vol. 32, no. 9, 2007, pp. 471–72.

- Horne, Rob et al. “Medicine in a Multi-Cultural Society: The Effect of Cultural Background on Beliefs about Medications.” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 59, no. 6, 2004, pp. 1307–13.

- Improving Cultural Competence. US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014.

- Melonçon, Lisa K. “Patient Experience Design: Expanding Usability Methodologies for Healthcare.” Communication Design Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 2, 2017, pp. 19–28.

- Napier, A. David et al. Culture Matters: Using a Cultural Contexts of Health Approach to Enhance Policy making. World Health Organization, 2017.

- St.Amant, Kirk. “The Cultural Context of Care in International Communication Design: A Heuristic for Addressing Usability in International Health and Medical Communication.” Communication Design Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 2, 2017, pp. 62–70.

- —. “Culture and the contextualization of care: A prototype-based approach to developing health and medical visuals for international audiences.” Communication Design Quarterly, vol.3, no. 2, 2015, pp. 38–47.

- Sartorius, Norman. “The Meanings of Health and Its Promotion.” Croatian Medical Journal, vol.47, no. 4, 2006, pp. 662–4.

- Thomas, Paul. “Understanding Context in Healthcare Research and Development.” London Journal of Primary Care, vol. 6, no. 5, 2014, pp. 103–5.

Keywords: care, context of care, culture, rhetoric of health and medicine (RHM)

Cover Image Credit: Artist: Nick Bustamante is a Professor of Art and currently serves as the Studio Program Chair in the School of Design at Louisiana Tech University. Bustamante is co-fonder of the Visual Integration of Science Through Art program (VISTA) which over sees academic programs in Pre-Medical Illustration and Scientific Visualization. Websites: bustamateart.org, latechvista.weebly.com

Kirk St.Amant is a Professor and Eunice C. Williamson Endowed Chair in Technical Communication at Louisiana Tech University and is an Adjunct Professor of International Health and Medical Communication with the University of Limerick in Ireland. He is also a Research Faculty member with Louisiana Tech’s Center for Biomedical Engineering and Rehabilitation Science (CBERS) and is the Director of Tech’s Health and Medical Communication Center.

Kirk St.Amant is a Professor and Eunice C. Williamson Endowed Chair in Technical Communication at Louisiana Tech University and is an Adjunct Professor of International Health and Medical Communication with the University of Limerick in Ireland. He is also a Research Faculty member with Louisiana Tech’s Center for Biomedical Engineering and Rehabilitation Science (CBERS) and is the Director of Tech’s Health and Medical Communication Center.  Elizabeth L. Angeli

Elizabeth L. Angeli