Rhetorical Empathy in Dustin Lance Black’s 8: A Play on (Marriage) Words

“I’m willing to entertain the fact that some people are uncomfortable with the idea that gay people are just like us.”

—Martin Sheen as attorney Ted Olson in 8

Background on 8 the Play

The recently debuted 8, a play by Dustin Lance Black, the Oscar winning screenwriter of Milk, recreates the June 2010 trial that overturned Proposition 8 (Prop 8) in California. The lawsuit giving rise to the trial involved two couples—one lesbian and one gay—who sued the state of California for the ability to marry under California law, a right that had been taken away by the passage of Prop 8. The case could very well be described as the Scopes trial1 of the gay rights movement, pitting secular vs. religious arguments against LGBTQ people that fall miserably flat in the twenty-first century. Black based his ninety-minute play on twelve days of trial transcripts, interviews with the two couples who served as plaintiffs, and firsthand accounts of the proceedings.2

8, also known as 8 the Play, debuted on Broadway on September 19, 2011, and has since been performed widely at community theaters and university campuses. In the analysis that follows, I focus on the version of 8 that was performed live at the Ebell Theatre in Los Angeles on March 3, 2012. The play was live streamed on YouTube and, as of this publication, is still viewable. Broadcasting a play live on YouTube marks a significant shift in making what normally is considered an elitist genre of theater available to audiences on a much wider scale. The decision of the play’s producers to make the LA performance available on YouTube, as well as releasing the script and production rights to theater groups across the US, aligns with the exigency of the play: to expose the arguments made in the Prop 8 trial to a wide audience.

The plaintiff’s legal counsel, the unlikely pairing of Ted Olson and David Boies, believed that showing the public what actually happened in the courtroom would be a devastating blow to antigay rights battles in the court of public opinion, but a Supreme Court decision barred videos or live feeds of the trial. Black’s 8 was born out of this ruling. He takes a courtroom transcript with legal arguments and jargon and puts flesh and blood on it by creating two couples who are carefully constructed not “simply” as gay or lesbian but also as human beings with hopes, fears, loves, and lives the play’s audience can relate to.

8 features a condensed reenactment of the Prop 8 trial as well as fictional exchanges between the two couples and between the lesbian partners and their two teenage sons that act as a rhetorical frame. A short dialogue between the two sons forms the opening scene, and several other fictional dialogues and monologues break up the snapshots of the actual court proceedings, intended to provide the audience with a more personal experience of the trial and its effects on real people. What began, then, as an alternative way of getting the trial contents out to the public becomes, in 8, something much more rhetorically strategic than an O. J. Simpson-style live courtroom drama: Black humanizes and personalizes the arguments for and against gay rights. More specifically, I argue here that by employing rhetorical empathy—appeals to emotion and personal connection based on shared experience—the play creates a strategic identification between straight and gay people to further the cause of gay rights.

The questions that drive this inquiry and analysis are as follows: How does rhetorical empathy function in 8? How can we situate the function of rhetorical empathy in 8 within the larger context of appeals by the LGBTQ community for equal rights? And, finally, what does this site of analysis suggest about the value of rhetorical empathy as an inventional strategy and heuristic for engaging with the Other?3

Rhetorical Empathy

The strategy of using emotion and personal connection has a long history in Euro-American rhetorical history, dating back to Aristotle’s notion of pathos and more recently to Kenneth Burke’s theory of rhetorical identification. I define rhetorical empathy as a way of extending Burke’s identification by entering into the experience of the Other using appeals based on emotion and personal connection. Rhetorical empathy functions as an inventional topos and a rhetorical strategy, a conscious choice to connect with an Other, and also as an unconscious, often emotional, response to the experience of others.

In Euro-American epistemology, specifically within psychology, empathy often is associated with either cognition/thought or affect/emotion: cognitive empathy and affective empathy; however, recent work in cultural studies (Ahmed), rhetorical theory (Gross), and neuroscience (Decety and Meyer 1074) has complicated the degree to which emotions (including empathy) are hardwired components of our biological makeup or cognitive functions highly depending on context and learned behavior. Rhetorical empathy is a recursive process that may involve both cognition (conscious choice) and affect (which may be unconscious but is constructed by culture nonetheless). Although characteristics of empathy weave throughout the history of rhetoric and composition as a discipline in both theory and classroom practice (Burke’s identification, Rogerian rhetoric, Wayne Booth’s listening rhetoric, Krista Ratcliffe’s rhetorical listening), empathy has yet to be conceptualized as a rhetorical strategy or topos.

As an inventional stance, rhetorical empathy offers a way “in” to challenging discursive engagements between polarized groups. As a rhetorical strategy, rhetorical empathy focuses on the embodied subject position of both the rhetor and an Other in the form of lived experiences. Choosing to identify with an Other who may be hostile involves vulnerability and risk, but such a strategy offers possibilities for engaging across difference. As a somewhat conservative, nonconfrontational rhetorical strategy, rhetorical empathy can open doors to discussion and address fears and threats that may prevent listening and engagement.

Rhetorical empathy functions by establishing a connection based on shared emotion and, relatedly, shared points of identity.4 In Rhetorical Listening, Krista Ratcliffe critiques Burke’s identification for allowing only for “necessary” difference and rejecting the rest in favor of common ground and for ignoring differences in the cultural and political positions of various subjects, a critique that could be leveled at much of modern rhetorical theory (47-49). Rhetorical empathy assumes that shared identification/identity can be a starting point for rhetorical dialogue and engagement that recognizes unequal power relationships, historical context, and systemic and institutional forms of oppression. After an initial threshold of analogous identification has been established (e.g., in 8, the argument is that gay and lesbian couples are similar to straight couples), rhetorical empathy can create openings to highlight difference and unequal power relationships, as I demonstrate in my analysis below.

Rhetorical Empathy in 8

Rhetorical empathy functions in 8 on a number of levels: by appealing to emotion and pathos, to shared identity, and to shared experiences that attempt to reduce the Other’s sense of threat and promote empathy.

In the lead-up to the vote on Prop 8 in 2008, the logos-based appeals the “No on 8” campaign used to counter the antigay “Yes on 8” rhetoric fell flat with voters. This failure highlights Sharon Crowley’s argument in Toward a Civil Discourse that progressives will fare much better countering fundamentalism with other, more expansive tools offered by classical rhetoric—including pathos—rather than with logical appeals and reason as relics of an Enlightenment approach to public discourse (23). Three of the most prominent and egregious thirty-second commercials produced by the “Yes on 8” campaign prior to the vote on Prop 8 are shown to the audience during 8 so that they become part of the script itself. The arguments in the commercials appeal to fears that marriage equality would undermine “traditional” marriage, would threaten religious freedoms, and that children would be “exposed to homosexuality” in schools despite their parents’ disapproval.

Unlike 8 the Play, which uses a personalized, emotion-based approach that I’m characterizing as rhetorical empathy, the “No on 8” strategy focused on logical appeals attempting to refute the falsehoods in the pathos-laden “Yes on 8” commercials. A prominent example, “Proponents of Prop 8 Are Using Lies to Scare You” features a calm, male voice reasoning with viewers to reject the fear-based “Yes on 8” rhetoric. After all, the voice-over declares, “they’re using lies to persuade you. Prop 8 will not affect church tax status; that’s a lie. And it will not affect teaching in schools; that’s another lie. It’s time to shut down the scare tactics.”

Another prominent appeal in 8 the Play associated with rhetorical empathy involves creating a sense of shared identity between the characters in the play and the audience as well as personalizing the experiences of the two plaintiff couples so that the issues raised by the play become more than legal problems to be solved and falsehoods to be countered. The choice of the plaintiffs themselves and their portrayal in the West Coast premier on YouTube represents an embodied form of rhetorical empathy designed specifically to reduce the sense of threat to straight audiences that same-sex marriage may elicit.

For example, nearly all of the actors portraying the real-life lesbian and gay couples in 8 identify as straight: only Matt Bomer has publicly identified as gay. In the play, the plaintiffs and their kids are portrayed as real people whom their straight audiences can relate to, with backgrounds, life histories, love stories, and kids who get on their nerves, but whom they care deeply for. The plaintiffs are also portrayed as unwilling activists who simply want to live their everyday lives with their spouses and kids without being harassed or made to feel inferior because they’re gay. In the first scene, for example, one of the teenage sons of the lesbian couple—Eliott—says of his moms, “You associate the word activism with signs and extremists. When I think of Kris and Sandy I think of people who . . . don’t force their views on people” (1:20). This nonthreatening “we’re just like you” approach attempts to create a sense of identification with the potential audience of the play who may be turned off by a more direct, confrontational approach to the arguments at issue, specifically an audience beyond those (likely supporters) at the LA premiere who may see the recorded performance on YouTube or the play performed at a high school, college, or community theater.

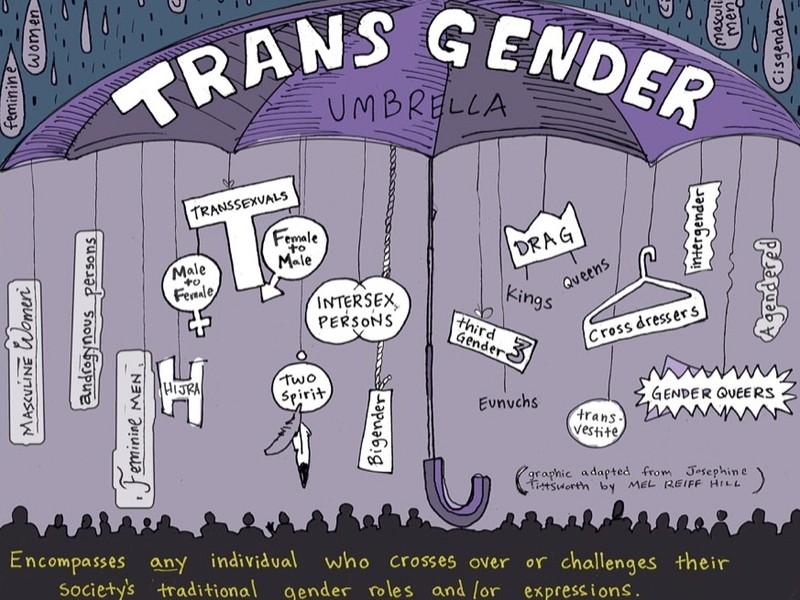

Rhetorical empathy functions in the play as a form of strategic essentialism; the characters are, for the most part, heteronormative in their appearance and gender performance, and, except for the fact that they’re gay, they could easily be a member of any one of the straight couples in the audience. The queer in LGBTQ is erased, and what 8 portrays is two couples who could be the straight couples next door in the suburbs but who just “happen” to be gay. Reinforcing this strategy is the argument made by Olson and Boies in the play that being gay is an immutable orientation. This is not gay life in the Castro as in Milk; this is mainstream gay life in the same vein as 2011’s The Kids Are All Right, intended to put an attractive, palatable face on the Other, on the enemy who the “Yes on 8” campaign suggests just might be coming after your children—after he or she comes home from work, takes his or her own kids to soccer practice and attends the PTA meeting.

Once the audience has been invited to identify and empathize with the couples as a metonymic representation of gay couples, they’re invited to imagine what it’s like to be blatantly discriminated against. In one scene Jeff and Paul describe their relationship to the audience by facing them directly, creating an intimacy and deeply personal tone in the play. Jeff says, “It’s always an awkward situation at the front desk of a hotel. The individual working at the desk will look at us, perplexed: You ordered a king-sized bed. Is that really what you want?” (8:20). Paul adds, “Unless you have to go through that constant validation of self, there’s no way to really describe how it feels . . . . I can’t speak as an expert; I can speak as a human being who’s lived it” (9:06). In another scene Kris describes the emotional toll of having to make the constant decision whether to come out “at PTA, at soccer; it’s exhausting” (34:37). Paul implicitly asks the audience how it would make them feel to be considered a threat to children:

When I think of protecting your children, you protect them from people who perpetrate crimes against them . . . but when I think that my marrying Jeff is going to harm some child somewhere, it’s so damning and so angering (sic) because if you put my nieces and nephews on the stand right now, I’d be the cool uncle. To think that you have to protect someone from me, from Jeff and from our community, there’s no recovering from that. And unless you’ve experienced that moment, regardless of how proud you are, you feel ashamed. (38:52)

In 8, rhetorical empathy, characterized by analogous appeals based on similarities, becomes a process-focused appeal that invites an audience to imagine what it is like on the other side of the binary of gay/straight and then to, at least rhetorically, deconstruct the unequal power distribution within that binary. As an alternative to logos-based appeals, rhetorical empathy in 8 both enacts and invites vulnerability by appealing to emotions, to embodiment, and to shared experiences. As a form of strategic essentialism, approaches based on rhetorical empathy risk over essentializing, in the case of 8, a diverse group of people who identify along the LGBTQ spectrum. Despite its risks, rhetorical empathy offers possibilities for engagement between groups that may not normally engage with one another based on historical and cultural differences and harmful stereotypes. A rhetorical stance and way of being in the world characterized by rhetorical empathy requires that we see the Other as a real person rather than as a disembodied, threatening argument—someone who may be more like us than we want to believe.

Endnotes

- The Scopes trial (1925), a landmark legal case pitting Christian fundamentalist against modern scientific worldviews, involved a high school teacher in Dayton, Tennessee, John Scopes, being tried for teaching evolution in violation of the Butler Act (1922), which outlawed the teaching of evolution in state-funded institutions (“Scopes”). The trial has striking parallels to the Prop 8 trial: famous litigators in Clarence Darrow, representing Scopes for the American Civil Liberties Union, and William Jennings Bryan, arguing for the state in defense of a religious fundamentalist view of US civil society and education, and a focus on the implications of teaching evolution (or, as Prop 8 proponents claimed, teaching about gay marriage) to children in public schools. return

- The August 4, 2010, ruling of Chief District Court Judge Vaughn Walker (played by Brad Pitt in 8) on Perry v. Schwarzenegger for the US District Court for the Northern District of California held that Proposition 8 violated the Due Process and Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Chief Judge Walker’s ruling was immediately appealed. On February 7, 2012, a three-judge panel for the Ninth District US Court of Appeals affirmed his decision in the case, now known as Perry v. Brown (“Perry”). Appeals continue now to the eleven-member Ninth Circuit Court and then to the Supreme Court. return

- I am relying on concepts of the Other in Simone de Beauvoir and Michael Warner (gender) as well as in Edward Saïd (nationality and race). return

- Here I rely on intersectionality theory, articulated by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw and Patricia Hill Collins as a critical consciousness of “particular forms of intersecting oppressions—race and gender or sexuality and nation” (Collins 21). An awareness of multiple subject positions and intersectionality complicates ways in which rhetors can approach Others within polarized discourse. return

Works Cited

- 8. By Dustin Lance Black. Dir. Rob Reiner. Perf. Martin Sheen, Brad Pitt, George Clooney, Christine Lahti, Jamie Lee Curtis, Matthew Morrison, Matt Bomer, Chris Colfer, Kevin Bacon, John C. Reilly. Ebell Theatre, Los Angeles. 3 Mar. 2012. YouTube. Web. 15 Mar. 2012. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qlUG8F9uVgM>.

- Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print.

- Aristotle. On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse. Trans. George A. Kennedy. New York: Oxford UP, 1991. Print.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. 1952. New York: Vintage, 1989. Print.

- Booth, Wayne. The Rhetoric of Rhetoric: The Quest for Effective Communication. Malden: Blackwell, 2004. Print.

- Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. 1950. Berkeley: U of California P, 1969. Print.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2009. Print.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” In Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. Ed. Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw. New York: New P, 1995. 357-83. Print.

- Crowley, Sharon. Toward a Civil Discourse: Rhetoric and Fundamentalism. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006. Print.

- Decety, Jean, and Meghan Meyer. “From Emotion Resonance to Empathic Understanding: A Social Developmental Neuroscience Account.” Development and Psychopathology 20 (2008): 1053–80. Print.

- Gross, Daniel. The Secret History of Emotion. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2006. Print.

- “Perry v. Brown: S189476.” California Courts: The Judicial Branch of California. Judicial Council of California / Administrative Office of the Courts, 2013. Web. 2 Apr. 2012. <http://www.courts.ca.gov/13401.htm>.

- Ratcliffe, Krista. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2005. Print.

- Saïd, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1979. Print.

- “The Scopes Trial.” eHistory. Ohio State University Department of History, 5 Aug. 2010. Web. 6 Aug. 2012. <http://ehistory.osu.edu/osu/mmh/clash/Scopes/scopes-page1.htm>.

- Warner, Michael. The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1999. Print.

Lisa Blankenship is a doctoral candidate in Rhetoric and Composition in the Department of English at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. Her research interests include queer and feminist rhetorics, postmodern rhetorical theory, multimodal rhetoric and composition theories, and writing centers/writing across the curriculum. Before returning to the academy she was a creative director and graphic designer for ten years.

Lisa Blankenship is a doctoral candidate in Rhetoric and Composition in the Department of English at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. Her research interests include queer and feminist rhetorics, postmodern rhetorical theory, multimodal rhetoric and composition theories, and writing centers/writing across the curriculum. Before returning to the academy she was a creative director and graphic designer for ten years.