Baltimore’s Uprising: Diasporic Liberation, Consciousness, and Place

Since the onset of colonization and modernity, structurally-sanctioned violence has served as a global mechanism of racialized oppression towards people of African descent to maintain white supremacy and domination. In the United States, the legacy of such entities more often than not maintained a chameleon effect, giving the appearance of change while continuing to perpetuate oppressive structures. Baltimore, Maryland, exemplifies the results of these structural practices. These include historical and contemporary effects of redlining segregation, excessive police violence, high-level government corruption, and the gentrifying processes currently taking place.1

The death of Freddie Gray2 on April 19, 2015 sparked Baltimore’s inclusion as a center of the Black Lives Matter movement – a contemporary iteration of an African Diasporic liberation consciousness. Grey’s death and the events that followed were reported by media organizations in a way that served to perpetuate the racialized (mis)perceptions already in place, justifying actions taken by the state against Black communities and people in Baltimore. A substantive wave of media articles emerged articulating the realities of Baltimore3 and the narrative of events leading up to and describing the events of the Baltimore Uprising. They overtly demonstrated a processual tool called signification, which is perhaps more subversive and as detrimentally powerful as the government sanctioned-segregation of the 1900s,4 the brutal “Broken Windows”5 policing strategy, or the predatory Wells Fargo subprime mortgage lending6 that was a product of the 1980s-1990s racial projects.7

Methods and Positionality

I moved to Baltimore two years ago with a research interest in the relationship of cultural phenomena across African Diaspora regional zones, focusing on music and interaction. Corbin and Strauss’ naturalistic grounded theory orientation situates this research (16). I prepared this article in collaboration with local artist photographer Reuben “Dubscience” Greene and with the assistance of contacts in the community. I consider myself an “inside outsider.” I spent most of my youth growing up in Washington, DC, which has afforded me a certain level of regional belonging, yet am very much an outsider within Baltimore proper. I live on the edge of the Reservoir Hill and Penn-North boundary as a White woman in a predominantly Black neighborhood; I witnessed and experienced The Uprising and its aftermath, not intending to write about it.

Two months after The Uprising, Baltimore’s Health Department sponsored a series of “Listening Circles” throughout the city for community engagement and healing with a special emphasis on mental and emotional health. One of these circles, titled #DearBaltimore, featured three local artists: Dubscience, Nellaware, and Mateo Blu. They presented their photographs, short films, and paintings followed by an open dialogue with community members in attendance. I was present as a participant. Although I wanted to speak more, it was evident that as a White person in the space it was more appropriate for me to listen and observe than take a more active role in the dialogue.

Baltimore in the African Diaspora

The African Diaspora is a global phenomena, a method of inquiry, and an analytical lens for understanding the presence and construction of identities of African peoples and their descendants throughout the world. Ruth Simms Hamilton provides a sociologically-grounded framework for approaching the study of the African Diaspora and four categories of “social relations.” These shape and affect the lives of Africans and their descendants throughout the globe. They include: dispersion and mobility (geocircularity); oppression and racialization; connections to an African homeland (real and imagined); and the presence of communities of consciousness, which utilize cultural products as a mechanism for socialization, transmission, and social cohesion (11-33). These macro categories function intersectionally to influence identity formation in the diaspora as a multi-layered construct that includes (among many other facets) national, regional, and local concepts of belonging.

The nature of oppression and racialization based on the biologistic race concept is common throughout the globe, eliciting the need for active and intentional collective and self-liberation. I situate the Baltimore Uprising within this tradition: a continuation of a 500-year-long struggle of Africans and their descendants to live their humanity without interference and to combat the structural oppression and violence that has become sedimented throughout the world. The ideological manipulation of words, symbols, and meanings, is what Long calls signification. It contributes to the structural processes of oppression in ways that can be just as harmful and serve as the rationale for state-sanctioned modes of oppression (5-6). It impacts the hegemonic order’s perceptions of African-inspired diasporic cultural forms and Black communities’ engagement with places and spaces.

Signification is linguistically encoded on a spectrum of overt racism to microagressive communications. It also functions as a silencing mechanism, erasing narratives that challenge Euro-Western hegemony. Yet people do not just accept their oppression, nor being dehumanized. Long argues that it is a contradictory space for one in which to live, yet those within develop mechanisms articulating their humanness through creativity while honing the necessary defensive skills. The act of “playing” the signified language game and reconfiguring new meanings is what Long calls counter-creative signification wherein the “expressive deployment of new meanings [are] expressed in styles and rhythms of dissimulation” (8-9). It demonstrates intentionality, a concept defined by Jualynne Dodson as: “purposeful acts of a people, individually and collectively… focused on their partial or full liberation… [and] where they, as a group belong in the larger universal scheme of human activity” (37). This is manifested within African Diasporic cultural behaviors to help people maneuver and reassert their individual and collective selves within the oppressive confines of the Euro-Western hegemonic order: a regular and taken-for-granted process throughout the Diaspora.

Baltimore is undoubtedly an African Diaspora zone. As part of the “Up South,” it embodies what Pratt calls a contact zone and transculturation processes: a geographical stratified space where people of differing worldviews and knowledge constructs “meet, clash, and grapple” to form ways of being, distinctive to that particular space and place (4). The presence of various diasporic geosocial mobility waves are found within the Baltimore community. These include for example, Nigerian-based Ifa religious communities; Brazilian capoeira; an annual Caribbean Carnival celebration; and an African inspired indigenously Baltimore rhythmic form developed, taught, and expressed within the musical collective Urban Foli.

Contemporary perceptions of Baltimore have been mostly transmitted and propagated through the highly acclaimed HBO show, The Wire as it portrays “an American city in decline,” articulated in the companion book by Rafael Alvarez. It is precisely this image of Baltimore that was evoked by the mass media during The Uprising, counter-acting the reality of grassroots-level community organizing that has been in place for at least ten years. Many grassroots organizations have been working to foster mentorship and policy change, and to fight the ideological effects of signification and racism, focusing particularly on the youth. In the months just prior to The Uprising, concerted efforts were made to engage national and local violence, health disparities, and many other social issues faced daily. One example of this was the Conflict Transformation workshop developed by Dr. Wesley Days and co-led by Lisandra Ramos, sponsored by Equity Matters and a community-oriented business entity in Baltimore. This workshop, held a month before The Uprising occurred, utilized ritual processes rooted within African Diasporic concepts of interaction, cultural expression, and community formation:

“Conflict Transformation” by Dubscience Films

The implicit African Diasporic worldview and theatrical expression of early diasporic interactive processes elicited non-violent and productive strategies for negotiating confrontation. It allowed us to theatrically enact and conceptualize different modes of community and structural formation, approaches to social problems, and participatory action. This and many other forums, programs, and workshops have been doing the work to better the social conditions of Baltimore, empower youth, and change the signified perceptions of this city, all while struggling with funding and recognition.

The Death of Freddie Gray and the Baltimore Uprising8

As protests began at the Western District on April 18, one could hear discussions about police brutality in the streets, on local radio stations, and in local music shows among other spaces. I attended several events as part of my normative research, observing live music sessions that became spaces of therapeutic healing. Their performances evoked a communal and cathartic experience. At Kane Mayfield’s album release show on Friday April 24, local activist, media commentator, and community member Catalina Byrd spoke:

“Catalina Byrd at Kane Mayfield’s Return of Rap Album Release Concert” by Dubscience Films

Byrd’s comment “we don’t burn this city down, because the last time we did it, they didn’t rebuild it” lingered with me as I heard about the racial slurs thrown at protesters as they passed by Camden Yards baseball stadium that weekend. On Monday morning, April 27, 2015 I saw three news announcements: two from internet media outlets reporting a truce among the Crips, Bloods, and Black Guerrilla Family mediated by the Nation of Islam, and one from the police articulating “a credible threat” to kill police officers, later disproved by the FBI (see figure 1).

That afternoon I was driving from Washington, DC to Baltimore taking Gwynn Falls Parkway into the city. As I approached Mondawmin Mall to the left and Fredrick Douglass High School to the right at 3:01 p.m., I witnessed the police fully militarized and riot ready before the majority of Douglass students had even gotten out of school. I continued the rest of the way home, watching the events unfold from my window over the next six hours. I wanted to be out in community helping protect local stores, but was advised the presence of my White female body would do more harm then good. The events at Mondawmin and police actions were recounted in this article from Mother Jones, and what I witnessed corroborates this account. That night I went to a local gathering space, where some community members gathered. As two young White males attempted to evoke violence by throwing rocks off a roof, two respected Black community members stopped them, verbally holding them accountable for their actions. We spent the next few (surreal) hours watching one of the two corporate chain businesses on the block get looted. None of the independent businesses were touched.

Tuesday, April 28, 2015

Some of us gathered at a local community space, trying to strategize about what to do next. We created a free writing space for people to express themselves before heading to the Penn-North intersection, arriving around 10:30 a.m. We found a police line blocking westbound North Ave, and roughly 150 people in and around the intersection:

“Peace Against the Machine” by Dubscience Films

People came to Penn-North that day to participate and evoke community belonging within the space. We evoked spiritual practices sharing common African Diasporic concepts of community, energy healing, and collective social bonds. As Maya Talmon-Chvaicer writes, the “playing” of Capoeira, evokes an African Diasporic liberation and spiritual consciousness, as well as a connection to the space and place in which it is played (20-21, 26-31). We were told that CNN footage of the capoeira playing aired for a few hours, yet was not circulated as part of the dominant narrative. Articles such as this one from Democracy Now9 practiced a subtle form of erasure, selectively recounting events in a way that omitted the African Diasporic spiritual and liberation practices evoked in spaces where community gathered.

Healing Spaces in Community

The city was placed under curfew from 10 p.m. until 5 a.m.10 from April 28 until the morning of May 3. Those of us who had experienced live music shows in the week prior recognized the detriment caused by denying the community the space to gather and heal through productive, creative mediums. The curfew also resulted in financial cost to restaurants, clubs, and working musicians. We had been gathering during the prior week, and prohibiting that space, resulted in anger and resentment toward structural powers. The waves of violence surging throughout the city11 sparked the need for healing and collective action, prompting the #OneBaltimore initiative. As part of these efforts, the City Health Department facilitated a series of listening circles. One titled #DearBaltimore, served as an open forum for discussion and reflection:

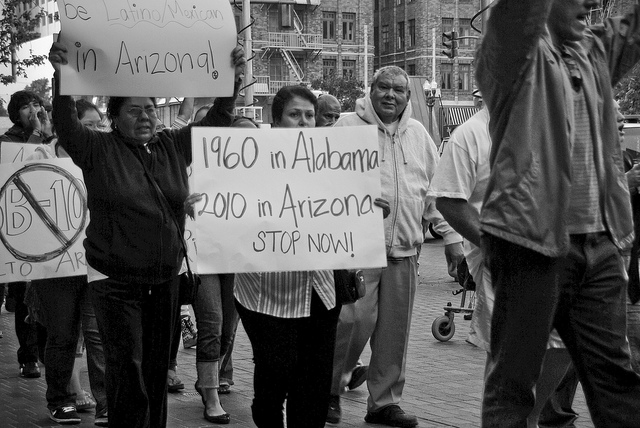

Two sessions were free to the public on Monday, June 29 from 12-2 p.m. and 5-7 p.m. with food donated by Terra Café.12 The artists presented short films and photographs to the audience, facilitating an open dialogue and free space for community members to articulate their voice. The first session had 12 people in attendance, including a brief visit from two leading city health department officials. The second session received up to 45 people and was intergenerational.13 People articulated a desire for more events such as this, connecting creative expression and the reality of their community disseminated in multiple spaces throughout the city. They spoke of a need to dismantle the normative modalities in a radical form in order to create something new. People reflected back and compared the Uprising events to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s and 60’s, posing questions about how many times these patterns were to be repeated.

Conclusion

The recent events in Baltimore stand as one example reflecting the larger picture of global racially-motivated oppression. From the terrorist attack on the Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston, South Carolina to the revoked citizenship rights of Haitian-descended Dominicans, systematic oppression within the African Diaspora continues its assault on Africans and their descendants throughout the globe through structural and organizational mechanisms. The language of Black Lives Matter exists not just as the newest iteration of an emancipatory struggle, but because signification effectively legitimates structural oppression. If we continue to question and infiltrate signified mechanisms of knowledge production, discourse, and symbolism, we are able to dismantle the structural and ideological buttresses of dehumanization. Empirical challenges to Euro-Western hegemonic ideological discourse occur in the everyday actions of people caring for each other and working with one another on a grassroots level despite structural blockades.

Endnotes

- See Simon McCormack’s Huffington Post article “What’s Happening in Baltimore Didn’t Just Start With Freddie Gray,” (April 28, 2015) for more context on Baltimore’s pre-Uprising social conditions. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/04/28/freddie-gray-baltimore-history_n_7161962.html return

- Although most often we see Freddie’s last name spelled as “Gray,” Roberto Alejandro’s On Background blog post “What’s in a Name: The Silencing of Freddie Grey,” states that he reportedly preferred the spelling of “Grey” and this author wishes to honor that choice (April 24,2015). http://www.onbckgrnd.com/?p=247 return

- One example is Time Magazine’s May 2015 issue. return

- Richard Rothstein’s Empathy Educates article “From Ferguson to Baltimore: The Fruits of Government-Sponsored Education,” (April 29, 2015). http://empathyeducates.org/from-ferguson-to-baltimore-the-fruits-of-government-sponsored-segregation/ return

- Matt Taibbi’s Rolling Stone article, “Why Baltimore Blew Up,” (May 26, 2015). http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/why-baltimore-blew-up-20150526?page=4 return

- See Bryce Covert’s Think Progress article, “The Economic Devastation Fueling The Anger in Baltimore” (April 28, 2015) http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2015/04/28/3651951/baltimore-freddie-gray-economic/ and the New York Times Editorial, “Racial Penalties in Baltimore Mortgages,” (May 30, 2015). http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/31/opinion/sunday/racial-penalties-in-baltimore-mortgages.html?_r=1&referrer return

- See Howard Winant’s book Racial Conditions (1994) for a conceptual explanation of racial projects and their impact on racialization (29-32). return

- Several newspaper outlets have compiled articles reflecting the timeline of events: The Baltimore Sun http://data.baltimoresun.com/news/freddie-gray/; NPR http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/05/01/403629104/baltimore-protests-what-we-know-about-the-freddie-gray-arrest ; and NBC News http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/baltimore-unrest/timeline-freddie-gray-case-arrest-protests-n351156 return

- Note that the person labeled “Unidentified” in the transcript is Eze Jackson, local Baltimore Hip Hop artist, community leader, youth mentor, and former president of Marylanders for Marriage Equality during the successful 2008 initiative to legalize same sex marriage. The exclusion of his identity was viewed by some as another example of the media’s erasure of Baltimore’s productive community action. return

- See this ABC News report “Hampden, other areas tell different story of Baltimore Curfew” (May 4, 2015). http://www.abc2news.com/news/crime-checker/baltimore-city-crime/hampden-other-areas-tell-different-story-of-baltimore-curfew on how white residents were treated differently while breaking the curfew. return

- See Peter Hermann’s Washington Post article “After rioters burned Baltimore, killings piled up largely under the radar” (May 17, 2015). http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/crime/violence-has-become-part-of-life-in-baltimore/2015/05/17/4909264a-f714-11e4-a13c-193b1241d51a_story.html return

- Part of Terra’s regular community efforts includes the Neighbors Without Walls program to serve Baltimore’s homeless population. return

- We originally wished to include response cards written by participants for inclusion in this article so that community members could articulate their feelings in their own voice, without being filtered through the author. However there was dissonance over the inclusion of this, despite the vocal announcement that the cards were optional and anonymous. In order to remain on the side of caution I have summarized some of the responses. I do so wearily and with the understanding that this reflects the “mainstream” dynamics of structure and academic research. return

Works Cited

- Alvarez, Rafael. The Wire: Truth Be Told. New York: Pocket Books, 2004. Print.

- Broadwater, Luke (lukebroadwater). “Remember this Baltimore police news release? It took the FBI less than a day to debunk news.vice.com/article/fearin…” June 24, 2015, 2:33 p.m. Tweet.

- Corbin, Juliette, and Alselm Strauss. Basics of Qualitative Research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2008. Print.

- Dodson, Jualynne E. Sacred Spaces and Religious Traditions in Oriente Cuba. Edited by David Carrasco and Charles H Long. Religions in the Americas 1. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2008. Print.

- Hamilton, Ruth Simms, ed. Routes of Passage: Rethinking the African Diaspora. Vol. 1. ADRP Series 1. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2007. Print.

- Long, Charles H. Significations: Signs, Symbols, and Images in the Interpretation of Religion. Aurora, CO: The Davies Group, 1995. Print.

- Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge Press, 1992. Print.

- Talmon-Chvaicer, Maya. Hidden History of Capoeira: A Collision of Cultures in the Brazilian Battle Dance. Austin,TX: University of Texas Press, 2008. Print.

- Winant, Howard. Racial Conditions: Politics, Theory, Comparisons. Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota Press, 1994. Print.

Cover Image Credit: Reuben Greene, Dubscience Photography, “Eye of the Storm.” Used with permission.

Alexandra P. Gelbard is a sociologist and creative scholar from Washington, DC living in Baltimore, Maryland. She works on the theoretical application of African Diaspora studies and her work addressed the connectivities across African Diaspora regional zones, specifically those of Cuba, New Orleans, and the DMV (DC-Maryland-Virginia). Her specializations include culture, music, race, religion, and consciousness.

Alexandra P. Gelbard is a sociologist and creative scholar from Washington, DC living in Baltimore, Maryland. She works on the theoretical application of African Diaspora studies and her work addressed the connectivities across African Diaspora regional zones, specifically those of Cuba, New Orleans, and the DMV (DC-Maryland-Virginia). Her specializations include culture, music, race, religion, and consciousness.