Visualizing Translation Spaces for Cross-Cultural Health Communication

Visuals are often used to supplement or replace written or verbal language for quick, accessible communication. This perspective has been especially true in cross-cultural healthcare situations, where visuals have been endorsed as strategies for addressing the challenges and complexities of communicating with audiences who may have varied ways of speaking and reading texts (Doak, Doak, and Root 67; Osborne 30-31; US DHHS 4.3; WHO 3).

Consider the mosquito emoji the Unicode Consortium approved for release in 2018. Some have touted it as an effective mechanism to provide members of the general public with a way to share diagnoses or to warn friends to take precautions (Shaivitz and Chertack 2; Webb and Mackay). We do not doubt that a visual like the mosquito emoji might be recognized and used by diverse groups across varying contexts. But would it really facilitate meaningful communication about public health hazards like Zika? Although organizations such as the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs are hopeful this will be the case, the use and impact of such visuals on health communication are yet to be determined. In the meantime, we see the buzz about the mosquito emoji as an opportunity to reflect on the use of visuals in health-related materials for cross-cultural contexts—and how to do it more effectively and ethically.

In this piece, we demonstrate how health communicators working in cross-cultural contexts can approach their design of visual communication more productively as translation spaces. We call for more ethnographic and engaged approaches to research on cross-cultural visual health communication. We also provide recommendations for navigating the translation spaces of visual health communication with a design process that works from the ground up. The key is considering how visuals constitute and circulate through translation spaces. To do so, we suggest health communicators who design or use visual materials can better account for the lived contexts and priorities of their target audiences by centering community expertise and collaboration in the design process.

Translation Spaces

Given the complexities of cross-cultural healthcare, health communicators must consider how their texts will be translated and used by audiences who might communicate and read in different ways (Ding 43; St.Amant, “Culture” 38-39). One way to examine how visuals communicate with audiences across cultural contexts is analyzing the translation spaces of public and community health work. Rachel Bloom-Pojar defines a translation space as any space “where translation work is required for negotiating meaning making across modes, languages, and discourses” (9). This concept emerged from her research with a summer health program in the Dominican Republic. It serves as an analytic frame for visualizing the dynamic interactions between two or more individuals as they negotiate differences in their understanding and use of texts, languages, terminology, and culture. Individuals cultivate these translation spaces when faced with the messiness of working through misunderstandings and conflicting notions of healthcare.

Previous work on translation spaces focused on verbal elements, but visuals are also part of these interactions. As we discuss below, visuals encounter a variety of translation spaces as audiences read, discuss, and use them. When considering how to compose visuals that are adaptable across translation spaces, health communicators should turn to community members, interpreters, and translators to discuss how individuals might interpret visuals across cultural contexts. Inspired by our previous work with ethnography, we see sustained engagement with communities “on the ground” of cross-cultural health as a method to connect translation and localization (Gonzales and Zantjer 273; Batova and Clark 223)with the overall process of creating effective, ethical visual health communication for cross-cultural audiences.

Visual Design for Cross-Cultural Audiences

When designing visuals to engage multiple audiences (e.g., patients, health providers, families, and communities), we must first consider how different users translate them. Like when choosing the words we use, visuals also need careful attention. As mentioned, visuals are often deployed as tools to simplify communication with publics and patients who communicate differently from health professionals and public health officials. When visuals are used to “transcend” language, or avoid language differences, a key component is disregarded: Visuals are not necessarily transparent, objective, or universally understood (Aiello and Thurlow 148; Dragga and Voss 266; Dumit 112; Kostelnick and Hassett 20-42; Kress and Van Leeuwen 3). In other words, visuals do not simply display or show information; they are rhetorical and “perform persuasive work” (Wysocki 124).

Individuals’ health histories, cultural ways of communicating, and local contexts all impact how people read, take up, and create visuals related to their health. As shown by Liping Bu’s study of American public health materials in China (28-30) or Tonya Smith-Jackson and Abeeku Essuman-Johnson’s analysis of safety symbols (46), a one-size-fits-all approach is no more appropriate for visual communication than it is for verbal.

Additionally, health communicators should be aware of their own cultures as being high- or low-context as studies like that of Julie Gathoni Muraya et al., which shows how abstinence campaign visuals missed the mark for Kenyan youth, and “posters could be read in many different ways depending on the context in which the situations that the posters portrayed were assumed to be occurring” (522). If we begin the design process by considering how visuals circulate across contexts, we acknowledge cultures have rich visual languages and lives that might entail different ways of reading or translating an image.

We must also consider the different agents that translate those visuals, whether computer, human, or otherwise. Just as people interpret visuals and assign words or other signifiers when looking at them, a computer might also assign written words to a visual if someone uses a screen reader. We must think through not only how individuals would translate the meaning of a visual for their own purposes but also how medical teams might use it to facilitate dialogue or persuade communities to approach their health in a certain way.

Working with Complexity

Health communicators and their audiences would benefit from creating visuals that demonstrate the intricate relationships and agency that people can take up in caring for their health. Such visuals can better avoid the traps of patronizing, stereotyping, or trivializing a given local culture; they are usable, meaningful, and they better reflect the complexity of translation spaces.

As Danielle DeVasto has shown in her work on risk communication, visuals that reflect the complexity of the situation are more likely to configure people as having agency (133). Such representation may include greater numbers of humans and non-humans with more intricate relationships and connections; they also depict a range of actions, such as ones that are danger preventing, danger reducing, and neutral. Such visuals can better avoid extreme responses (e.g., “falsely optimistic” or “doomed”), creating multiple pathways and strategies for action and greater opportunities for engagement.

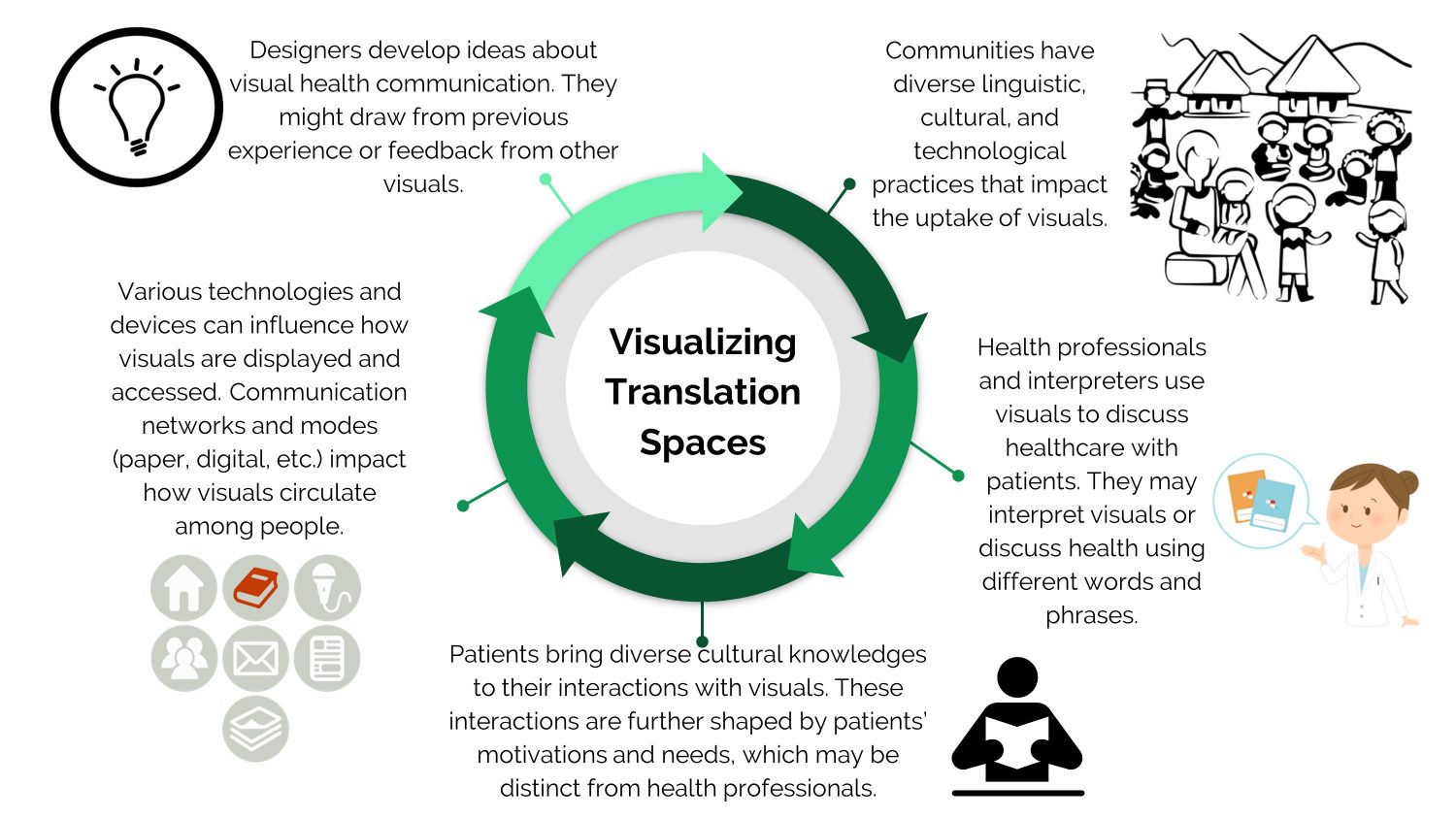

To demonstrate how visuals can represent the complexity of cross-cultural contexts, we composed Figure 1. This figure illustrates various factors that impact how visuals circulate through translation spaces for health communication.

In this visualization of translation spaces, various linguistic, cultural, and technological practices of communities impact the uptake and interpretation of health communication. These factors make it difficult to generalize what is most effective for multiple audiences or even multiple people from the same culture.

Localizing Visual Designs for the Translation Spaces of Healthcare

In order to develop a deeper sense of how translation spaces function and take steps to prepare their visuals for adapting to the uncertainty and complexity of the dynamics of these spaces, health communicators can turn to ethnographic methods for localizing visuals with community stakeholders who can provide insight into their local contexts. As Lee Brasseur claims, “Visual forms of communication that rest in the community, that have a heuristic function, and that are produced and shared collaboratively are clearly the most successful” (147). By engaging with communities and observing how texts are translated by different people, health communicators can better design visuals that will adapt within and across contexts. To localize visuals in this way, we suggest the following steps:

- Collaborate with communities. Early in the design process, connect and collaborate with members of target populations to design visuals that reflect their input and expertise. Continue to invite participation throughout the process through methods like interviews and participant observation to gain insight into local design patterns and preferences.

- Work with translators and interpreters. Have conversations with translators and interpreters to discuss different ways to phrase and represent topics related to or represented in the visuals. Incorporate their feedback and compensate them for taking the time to help develop the visuals.

- Research the user experience. Utilize methods such as focus groups, field studies, surveys, and usability testing to gather insight into how community stakeholders interpret and experience using the visuals for discussing or managing their own health.Try out computer-based translators and screen readers to see and hear how messages may change when various software interacts with the visuals.

- Revise designs. Revise and adjust the design of the visuals based on the feedback received and the patterns observed during the user-experience testing. Given the dynamic nature of cultural associations, consider how visuals may be revised and updated in the future, and set up processes to facilitate future revision work by community stakeholders.

- Finalize visuals. Decide with community partners when the visuals are ready to be finalized. Share details from the testing and revision processes to make rhetorical choices explicit. Provide files that could be edited by collaborators or formalize a process for updating and/or adjusting the visual(s).

We present these steps as a potential process with the intention of repeating, revising, and reconsidering based on community input and user-experience testing. This builds on Laura Gonzales and Rebecca Zantjer’s suggestion to rhetorically layer strategies that “exemplify the complex negotiation of history, culture, and language that takes place as users translate words and phrases” (280).

Localizing visuals also includes thinking about the motivations, decisions, and needs individuals have. Health communicators working with visual designs should dedicate time toward learning about local conditions, locally available resources, and local experience in order to make technical content more accessible and help individuals develop emotional connections and meaningful experiences with the health issue being represented. In addition to using the strategies mentioned above to build this knowledge, health communicators might also analyze existing visuals or critically apply Hofstede’s and Hall’s cultural dimensions (e.g., high/low context, individuality/collectivism) (Brumberger 95-98). By first developing a sense of variations in visual language across cultures, health communicators can then strategically decide when and how to match or push back against audiences’ visual expectations.

Collaborating with Communities

By centering community practices and expertise, localization can guide the design process of visual health communication. A more nuanced awareness of the local particularities of a design element like color can help designs avoid faux pas, inspire fresh creative avenues, and enrich the visual language with extra layers of meaning. (See Candice Welhausen’s analysis of color use in Ebola-related infographics.) An awareness of local particularities also includes considering the interplay and translation of the written aspects of visuals, such as the space that different languages take up, how words are visual and cultural, and how images and words interact.

Collaborating with communities not only increases engagement with the health issue at hand, but it also provides insight about the community’s material conditions. This collaboration includes understanding how people may access the health visuals and how that access may be impacted by things like infrastructure and bandwidth. For example, visuals designed to load quickly or print coherently in color or black and white can help ensure more successful communication, even in areas with limited resources. Visuals should also reflect the available medical and health materials. People from different countries might have different expectations of what a clinic setting or a medical instrument looks like or what is available (St.Amant, “Aspects” 9). Visuals that reflect these local distinctions will likely be considered more credible, and thus more likely to contribute to people acting in ways aligned with the purpose of the text (St.Amant, “Culture” 39).

Seeing community members as collaborators rather than passive audiences acknowledges the rich visual languages and lives of their cultures. Such an approach resists simplistic notions of visuals and deficit models for communicating with people who are seen as lacking certain language abilities. This deficit model may also privilege the goals and needs of public health officials over those of local communities.

Concluding Thoughts

Visuals circulate through translation spaces that will differ depending on local contexts, communicative strategies, and individuals’ needs and interests. Ultimately, translation spaces are potential sites for transformation. By considering the translation spaces of the design process, health communicators can transform their visual practices through deep engagement with diverse communities and contexts across cultures. By centering localization and community expertise in the design process, visuals can work with people, culture, language, and difference rather than attempting to be a simple solution for the complexities of cross-cultural health communication.

Works Cited

- Aiello, Giorgia, and Crispin Thurlow. “Symbolic Capitals: Visual Discourse and Intercultural Exchange in the European Capital of Culture Scheme.” Language and Intercultural Communication, vol. 6, no. 2, 2006, pp. 148–62.

- Batova, Tatiana, and David Clark. “The Complexities of Globalized Content Management.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 29, no. 2, 2015, pp. 221-35.

- Bloom-Pojar, Rachel. Translanguaging Outside the Academy: Negotiating Rhetoric and Healthcare in the Spanish Caribbean. National Council of Teachers of English, 2018.

- Brasseur, Lee E. Visualizing Technical Information: A Cultural Critique.Baywood, 2003.

- Bu, Liping. “Cultural Communication in Picturing Health: W.W. Peter and Public Health Campaigns in

- China, 1912–1926.” Imagining Illness: Public Health and Visual Culture, edited by Serlin, Bu, and Cartwright, U of Minnesota Press, 2010, pp. 24–39.

- DeVasto, Danielle. Negotiating Matters of Concern: Expertise, Uncertainty, and Agency in Rhetoric of Science. 2018. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, PhD dissertation.

- Ding, Huiling. Rhetoric of a Global Epidemic: Transcultural Communication about SARS. Southern Illinois University Press, 2014.

- Doak, Cecilia C., Leonard G. Doak, and Jane H. Root. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. J.B. Lippincott, 1996.

- Dragga, Sam, and Dan Voss. “Cruel Pies: The Inhumanity of Technical Illustrations.” Technical Communication, vol. 48, no. 3, 2001, pp. 265-74.

- Dumit, Joseph. Picturing Personhood: Brainscans and Biomedical Identity. Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Gonzales, Laura, and Rebecca Zantjer. “Translation as User-Localization Practice.” Technical Communication, vol. 62, no. 4, 2015, pp. 271–84.

- Kostelnick, Charles, and Michael Hassett. Shaping Information: The Rhetoric of Visual Conventions. Southern Illinois University Press, 2003.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2006.

- Muraya, Julie et al.. “An Analysis of Target Audience Member Interpretation of Messages in the Nimechill Abstinence Campaign in Nairobi, Kenya.” Health Communication, vol. 26, 2011, pp. 516–24.

- Osborne, Helen. “Health Literacy: How Visuals Can Help Tell the Healthcare Story.” Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, vol. 29, no. 1, 2009, pp. 28–32.

- Shaivitz, Marla, and Jeff Chertack. Proposal for Mosquito Emoji, 2017, www.unicode.org/L2/L2017/17268-mosquito-emoji.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2019.

- Smith-Jackson, Tonya, and Abeeku Essuman-Johnson. “Cultural Ergonomics in Ghana, West Africa: A Descriptive Survey of Industry and Trade Workers’ Interpretations of Safety Symbols.” JOSE, vol. 8, no. 1, 2002, pp. 37-50.

- St.Amant, Kirk. “Aspects of Access: Considerations for Creating Health and Medical Content for International Audiences.” Communication Design Quarterly, vol. 3, no. 3, 2015, pp. 7–11.

- —. “Culture and the Contextualization of Care: A Prototype-based Approach to Developing Health and Medical Visuals for International Audiences.” Communication Design Quarterly, vol. 3, no. 2, 2015, pp. 38-47.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS). Quick Guide to Health Literacy. health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/Quickguide.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2019.

- Webb, Cameron, and Ian Mackay. “Will a New Mosquito Emoji Create Some Buzz About Insect-borne Diseases?” Smithsonian.com, 28 Feb. 2018, www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/will-new-mosquito-emoji-create-some-buzz-about-insect-borne-diseases-180968277/. Accessed 24 June 2019.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Risk Communication in the Context of Zika Virus. 2016. apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204513/WHO_ZIKV_RCCE_16.1_eng.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2019.

- Wysocki, Anne. “The Multiple Media of Texts.” What Writing Does, edited by Bazerman and Prior, Routledge, 2004, pp. 123-164.

Keywords: cross-cultural, translation, visual, ethnography, collaboration, health communication

Cover Image Credit:

Rachel Bloom-Pojar is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her research examines rhetoric in multilingual healthcare settings, with a specific focus on community discourses of health, Latinx rhetorics, interpretation, and promotores de salud (health promoters). Her book, Translanguaging outside the Academy: Negotiating Rhetoric and Healthcare in the Spanish Caribbean, was published in 2018 by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) as part of the Studies in Writing and Rhetoric series.

Rachel Bloom-Pojar is an assistant professor in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her research examines rhetoric in multilingual healthcare settings, with a specific focus on community discourses of health, Latinx rhetorics, interpretation, and promotores de salud (health promoters). Her book, Translanguaging outside the Academy: Negotiating Rhetoric and Healthcare in the Spanish Caribbean, was published in 2018 by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) as part of the Studies in Writing and Rhetoric series.  Danielle DeVasto is an assistant professor in the Department of Writing at Grand Valley State University. Her research primarily explores how expert and public stakeholders communicate about risk and uncertainty, especially in the contexts of natural hazards and science-policy decision making. Her work has been published in Science Communication, Social Epistemology, and the Journal of Business and Technical Communication. She also teaches courses that focus on how writing and rhetoric can help shape more livable worlds.

Danielle DeVasto is an assistant professor in the Department of Writing at Grand Valley State University. Her research primarily explores how expert and public stakeholders communicate about risk and uncertainty, especially in the contexts of natural hazards and science-policy decision making. Her work has been published in Science Communication, Social Epistemology, and the Journal of Business and Technical Communication. She also teaches courses that focus on how writing and rhetoric can help shape more livable worlds.