Burke, Black Metal, and the Golden Dawn: Deconstructing the Weaponized White Identity Politics of National Socialist Black Metal

Emboldened by a wave of populist resentment towards an increasingly globalized and integrated world, the radical right is seeing a resurgence. This has been true in Europe for nearly a decade, with many countries seeing increased popular support of far-right political parties, particularly in response to an influx of North African and Middle Eastern refugees and migrant workers. Racist violence has concurrently increased in Europe, according to a report carried out by the European Network Against Racism, and in the US, where a recent study by the Southern Poverty Law Center reported that the US’s biggest terrorist threat comes not from radicalized jihadists, but white far-right extremists.

Neo-Nazi and white supremacist organizations have long known how to appeal to this demographic through visual arts and music. The Nazis of WWII-era Germany famously co-opted the music of Wagner and classic Greek and Roman sculpture for propaganda purposes, but the white supremacists and neo-fascists who carry on their legacy today have found a more fitting tool to win the hearts and minds of today’s youth towards the cause: loud rock music.

It is not my goal to drum up an empty moral panic against a clique of sophomoric shock rockers, nor am I claiming that National Socialist Black Metal (NSBM) is likely to be terribly persuasive outside of the far-right fringe. The real danger that this kind of music poses is its power to radicalize those already in the scene to commit acts of violence, and to unify white supremacists from disparate national, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds. NSBM, unlike other forms of white supremacist music, is a global phenomenon and has more direct ties with real far-right politics. In the current global climate of resurgent far-right extremism, it would be irresponsible not to expose the rhetorical strategies these groups use as they whisper into the ears of their most volatile adherents. In this piece, I focus on the lyrics and imagery of popular NSBM bands and use Kenneth Burke’s theories of identification in rhetoric as a frame to understand their appeal.

Der Stürmer: A Case Study

Der Stürmer, living up to the propagandic goals of its namesake, exemplifies NSBM’s seriousness by being a longtime supporter of the popular Greek neofascist political party the Golden Dawn. Golden Dawn supporters have long been known for violence, ranging from the likely involvement of volunteers in carrying out the Srebrenica massacre of 1995 during the Bosnian War (Bistis 35-52) to the stabbing death of prominent left-wing rapper Pavlos Fyssas in 2013 as reported in the Guardian—facts made all the more disturbing by the presence of Giorgos Germenis, former bassist of Der Stürmer and current member of the band Naer Mataron, as a lawmaker in the Hellenic parliament.

He has been documented on YouTube to physically harass immigrant merchants and was reported by the Independent to have accidentally struck a small child in an attempt to attack the mayor of Athens. He remains active in the Greek NSBM scene.

Even though Kenneth Burke formulated his rhetorical theories during a very different time than the world of the early 21st century, his insights into the rhetorical power of identification become timely to consider as the far-right works to refine—and expand—its conception of white identity. Even identity politics rhetoric, formerly associated mostly with the left, has found its use in today’s far-right rhetoric. Identity is an increasingly powerful frame within which we engage in social, political, and cultural dialogues, and is crucial in understanding how white supremacists craft their appeals.

In Kenneth Burke’s A Rhetoric of Motives, notions of “identification” and “consubstantiality” are elaborated upon as essential elements in rhetoric. As Brooke Quigley clarified, “identification” is the key concept to differentiate Burke’s perspective from that of “a tradition characterized by the term ‘persuasion’” (1). Burkean identification begins with the very fundamentals of human communication: being physically distinct from one another, we use identification as a way to create togetherness with one another. We identify with others as our interests become joined, becoming what Burke calls “consubstantial.” Identification—and the creation of consubstantiality—can be said to be the mother of persuasion in Burkean terms. Laying this idea out in more abstract terms, Burke says the following: “A is not identical with his colleague, B. But insofar as their interests are joined, A is identified with B. Or he may identify himself with B even when their interests are not joined, if he assumes that they are, or is persuaded to believe so” (A Rhetoric of Motives 21).

The art of persuasion in rhetoric, according to this framework, ultimately boils down to identifying your interests with the interests of another. In order to persuade an audience, a rhetor must establish consubstantiality to bridge the gap created by our natural separateness. Indeed, because we are not literally conjoined with one another, consubstantiality must be created through rhetorical identification if individuals are to overcome this fundamental physical alienation and succeed in forming not only individual identity, but social relations as well (Davis 126). The successful rhetor, in other words, creates a world of shared meaning between rhetor and audience.

Establishing consubstantiality with an audience can take an explicit route such as the above wherein the rhetor creates common ground between the two by emphasizing shared qualities, but more implicit routes can be taken as well. George Cheney, in his 1983 study of organizational communication, highlighted two of these subtler manifestations of Burkean identification: identification through antithesis, whereby the rhetor establishes collective unity by establishing a common enemy; and identification by the “assumed we,” whereby the rhetor references “we,” “they,” and “us” to merge audience and rhetor interests regardless of how much—or little—the two have in common (148-149).

The kinds of division that stand to alienate the audience of an NSBM group like Der Stürmer from one another indeed inhabit all of these cultural, political, linguistic, and geographical spheres, and this is solved through the idea of “Pan-European” identity, articulated as such on their official website:

The Face of extinction will not be showed (sic) only to a White Nation, but to our Race as a whole. The Message of Der Stürmer is a Pan-European one. The Hellene and the Roman, the Nordic, the Slav and the Celt. All we are Brothers from the same womb and from the same Blood. Our Race is one, The Indo-European One, our Fatherland is one, and it has Hundred Flags, Europe! (Der Stürmer, “Biography”).

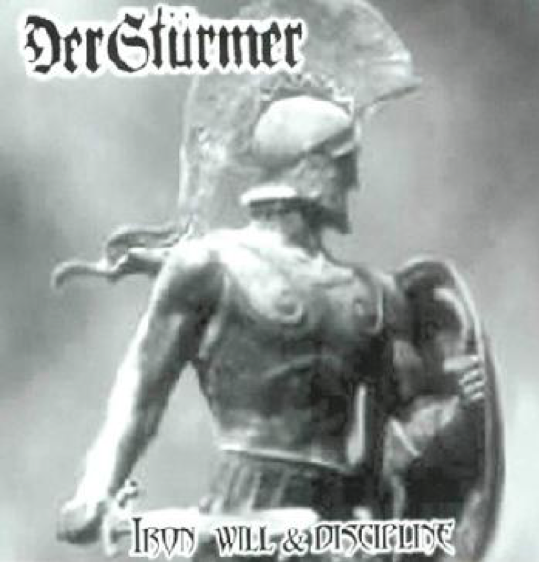

Der Stürmer’s artistic output takes every liberty with this conceit, gluing together a musical, lyrical, and visual panorama of European cultural and linguistic references, anchored by the fixed generic conventions of neo-Nazism and white supremacism. The lyrics to the song “Heathen Terrormachine” off the record Iron Will and Discipline illustrate this clearly, as do the accompanying album art (see Fig. 2):

Sickened to see the Europe of today

Multiracial chaos has its grip upon all

In this hour of Need have all gathered here

Steel-forged Bloodlines demand from us to act!

Hail the Heathen Terrormachine!

Hold no respect for everything that’s not Aryan

Trample down the parasites with scorn

Outlawed Heathen Rage terrorize the foreign hordes

Intolerant Hate burns deep within us all! (Der Stürmer, “Heathen Terrormachine”)

Der Stürmer are themselves Greek, and the album cover aptly features a bronze effigy of a Greek phalanx soldier. However, the lyrics clearly affirm the ethos stated on their website that calls for what the song reframes as a “Pan-European Army of Kinsmen” to wage war against the forces of “multiracial chaos,” “parasites,” “foreign hordes,” and the “chosen ones,” an apparent reference to Jews (the “chosen people of Israel”). They may be Greek, but they need not alienate potential audiences from other nations that also have a claim to membership within the “Pan-European Army of Kinsman,” as it were. Der Stürmer’s multinational inclusiveness may seem strange alongside the insular, exclusive nationalism ordinarily associated with Nazi ideology, but ultimately the Der Stürmer weltanschauung of essential Aryan identity and the primordial “steel-forged bloodline” serves to transcend national and political boundaries, framing the criteria for inclusion in the NSBM community as one item checklist for the audience to consider: Am I, or am I not, white?

Through the lens of Burkean identification theory, we can see that it is rhetorically useful for an NSBM band such as Der Stürmer to conflate visual and lyrical allusions both specific and general: specific to their own nation to imbue their rhetoric with nationalistic or regional pride, and the general use of the shared vernacular of NSBM bands such as “heathen,” and “Aryan” in their lyrics (not to mention the use of English instead of Greek to communicate their message). In Burkean terms it can be said that Der Stürmer uses the conceit of Pan-European identity as the compensator for the many domains of division separating a multinational spread of black metal devotees.

Identification as a rhetorical tool automatically implies a process of associating with others, but the glue that holds these associations together in Der Stürmer’s songwriting is that very thing Kenneth Burke claimed identification to remedy in the first place: division. It is a process of dissociation from others—an identification by antithesis—that keeps united this transcendent “Pan-European army of kinsmen.” Der Stürmer’s rhetoric of Pan-European inclusiveness is conspicuously juxtaposed alongside xenophobic invective, pitting the “Aryan Yeoman” against the aforementioned forces of “multiracial chaos,” “multiracial vermin,” “parasites,” “foreign hordes,” and the “chosen ones.” Just as it is rhetorically useful for Der Stürmer to avoid being too specific as to who stands to claim membership within the proverbial “Pan European Army of Kinsman,” equally useful is it to speak in generalities about the enemies that threaten it. From the point of view of their assumed audience, a shadowy enemy of “foreign hordes” and “multiracial vermin” is interpretable from the viewpoint of any white-dominant country in which multiculturalism, immigration, and increasing ethnic diversity is a controversial topic. Indeed, as Burke observes, “Men who can unite on nothing else can unite on the basis of a foe shared by all” (“The Rhetoric of Hitler’s ‘Battle’” 193).

In some cases, even less specificity is needed. Taken from a collaborative album between Der Stürmer and a German NSBM group Wehrhammer, the lyrics to the song “Vengeful Execution” imagine a battle, but the text mentions nothing specifically about who is on either side:

Repelled and Gloomy, but Strong in Will

Obsessed by Hatred and Thrilled to Kill

Fire that Burns inside, a Restless Need

In enemy’s blood my hands shall dripThe Shadow of Death will follow me

Trace the Scum that still walk free

A cesspool simmers in Decay for far too long

It’s time wash the trash off the sidewalk. . .Vengeful Execution

Holocaust to the youth of today

Vengeful Execution

What we Kill makes us Stronger (Der Stürmer, “Vengeful Execution”)

However, “White Demon” and “those remorselessly their Race betrayed” seem to tell us how we should read into the identities of the narrator and the “Scum” (sic), “trash,” and “vile kind” they mention. Even if the recurring theme of “Pan-European/Pan-Aryan” violence (and victimization) is not expressed with those terms, the song is readily interpretable as such from the viewpoint of a white supremacist. In the case of “Vengeful Execution” the implied author is in the first person, ultimately arriving at an assumed “we” at the last line, identifying the listener with the “White Demon” of this song, or the “Heathen Terrormachine” of the song of the same name, which also positions the listener among an assumed “we.”

In the world framed by Der Stürmer, nations and countries are essentialized into a single group fighting against a vague, stereotyped mob. Blurring the focus on the two sides in this struggle opens the possibility of listeners from any number of white-dominant countries to project themselves into these violent fantasies of protecting “Aryan Soil” from invading forces. In fact, Der Stürmer has collaborated with NSBM bands from Poland, America, Brazil, Canada, and Germany through collaborative albums like the aforementioned release in collaboration with the German NSBM project Wehrhammer (Der Stürmer “Releases”), and it is easy to imagine the same frame of ethnic tribal warfare waged between the same characters through the viewpoint of a Polish, American, Brazilian, Canadian, or German audience, provided the listener accepts Der Stürmer’s spurious ideological framework.

Through the rhetorical framework of Burke’s theory of identification, the ultimate goal of Der Stürmer as a vehicle for NSBM ideology can be said to be the creation of a consubstantial relationship with their audience. In A Rhetoric of Motives, he articulates this concept as thus:

In being identified with B, A is “substantially one” with a person other than himself. Yet at the same time he remains unique, an individual locus of motives. Thus he is both joined and separate, at once a distinct substance and consubstantial with another (21).

It seems clear that Der Stürmer and the wider NSBM scene have broken down enough walls of division between their audiences to establish a multinational network of consubstantiality between their listeners and fellow artists, even from nations that would seem antithetical to a genre of music that glorifies the Nazi war machine.

The Danger of Ignoring the Lunatic Fringe

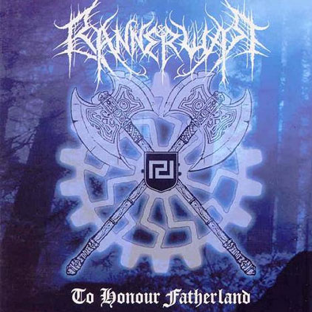

NSBM, while having a multinational spread of devotees, still exists squarely on the ideological fringe, even within the spectrum of far-right expression. Its obscurity notwithstanding, a number of Greek NSBM groups—Der Stürmer in particular—have focused the thematic angle of their artistic output to Greek nationalism specifically in recent years, printing on their album covers a Nazi-esque appropriation of the Greek meandros symbol such as that used by the Golden Dawn (see Fig. 3-6):

|

|

|

|---|

Fig. 3-5: From left to right: Wolfnacht “Αιμα και τιμη,” Bannerwar “To Honor Fatherland, “Patris “Servants of Hellenism.”

We take a tremendous risk by ignoring NSBM, even if it sits on the fringe of the ideological spectrum. Kenneth Burke similarly warned us in his 1938 review of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf:

Hitler’s “Battle” is exasperating, even nauseating; yet the fact remains: If the reviewer but knocks off a few adverse attitudinizings and calls it a day, with a guaranty in advance that his article will have a favorable reception among the decent members of our population, he is contributing more to our gratification than to our enlightenment (“The Rhetoric of Hitler’s Battle” 191).

From Mein Kampf to The Turner Diaries to Der Stürmer, history reminds us that even fringe beliefs can and will metastasize into something much worse if dismissed, and we see this again in the case of NSBM and its overt ties to the Golden Dawn.

Works Cited

- Bistis, George. “Golden Dawn or Democratic Sunset: The Rise of the Far Right in Greece.” Mediterranean Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 3, 2013, pp. 35-52.

- Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives. U of California, 1969.

- Burke, Kenneth “The Rhetoric of Hitler’s ‘Battle’.” The Philosophy of Literary Form. U of California, 1974, pp. 191-193.

- Cheney, George. “The Rhetoric of Identification and the Study of Organizational Communication.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 69, 1983, pp. 143-158.

- Davis, Diane. “Identification: Burke and Freud on Who You Are.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, Apr. 2008, pp. 123–147.

- Der Stürmer. “Biography.” DER STÜRMER – Hellenic Werwolf Kommando. The Pagan Front, 2007. Accessed 04 Apr. 2015.

- —. “Heathen Terrormachine.” DER STÜRMER – Hellenic Werwolf Kommando. The Pagan Front. Accessed 04 Apr. 2015.

- —. “Vengeful Execution” DER STÜRMER – Hellenic Werwolf Kommando. The Pagan Front. Accessed 04 Apr. 2015.

- Ethnikr. “Golden Dawn and Black Metal.”

- Quigley, Brooke L. ““Identification” as a Key Term in Kenneth Burke’s Rhetorical Theory.” American Communication Journal, vol. 1, no. 3, 1998, pp. 1-5.

Cover Image Credit: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Dawn_(political_party)#/media/File:Golden_Dawn_members_at_rally_in_Athens_2015.jpg

Keywords:

Jonathan F. Williams is a 2015 graduate of California State University, Chico, where he earned his B.A. in English. Upon graduating from college, he lived in rural China as an English teacher before returning to California. He will be attending Indiana University in the Fall of 2018 to pursue a Ph.D in rhetoric.

Jonathan F. Williams is a 2015 graduate of California State University, Chico, where he earned his B.A. in English. Upon graduating from college, he lived in rural China as an English teacher before returning to California. He will be attending Indiana University in the Fall of 2018 to pursue a Ph.D in rhetoric.