Anti-racist Activism and the Transformational Principles of Hashtag Publics: From #HandsUpDontShoot to #PantsUpDontLoot

Introduction

On August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, MO, unarmed black teenager Michael Brown was shot to death by police officer Darren Wilson. The aftermath of the shooting was marked by intense protests against state racism on the ground and in the digital sphere. Protesters relied on a variety of social media strategies that coordinated physical protests with the online circulation of images, speeches, music, and text. However, the same social media platforms that protesters mobilized to criticize Brown’s death became a means for counter-protesters to organize support for Officer Wilson and the Ferguson PD, deny the relevance of state racism to Brown’s killing, and delegitimize the voices of anti-racist protesters.

This essay suggests that social media both assists in the organization of anti-racist protests and facilitates the response of dominant publics attempting to counter those protests. By studying the hashtags #HandsUpDontShoot and #PantsUpDontLoot, we describe the close relationship between the technological affordances of hashtags and the unique possibilities as well as perils of the digital sphere as a site for the rhetorical labor of anti-racist organizing.

Hashtags allow activists and organizations to mobilize a rapid rhetorical response to pressing contingent events. By introducing the possibility of mimesis (repetition and mutation) and viral uptake, hashtags allow those using them to quickly form durable yet temporally delimited discursive connections. Because they structure the chaos of online conversation around semantically loaded phrases, the organizational logic of the hashtag aids in the rapid circulation of texts amongst strangers. However, the same principles that drive their rhetorical potency also subject hashtags to appropriative uptake by the social media apparatuses of state racism.

The argument emerges in four subsequent sections. In the first, we analyze the rhetorical properties of hashtags, exploring how social media in general and hashtags in particular facilitate the rapid, open-ended, and unpredictable formation of publics in digital space. The second section explores how these rhetorical principles play out in the exemplary hashtag #HandsUpDontShoot. The third section examines the appropriation and manipulation of #HandsUpDontShoot through the circulation of #PantsUpDontLoot. In the conclusion, we argue for the importance of visual and digital rhetorical studies for understanding the practice of online anti-racist organizing.

The Rhetorical Affordances of Hashtags

In this section, we discuss the affordances of social media that make hashtags rhetorically effective and suggest ways these affordances allow for unique modes of public organization online. The organizational and deliberative capacities of social media allow for the formation of publics that are simultaneously temporary and durable; organized and a-hierarchical; and divided by time, space, and social location but ultimately united in mutual attention to texts and events. In particular, we argue that the hashtag is a potent rhetorical tool for organizing publics in the digital sphere because it provides a means of coordinating conversation online without sacrificing the unpredictable and rapid circulation that makes social media a unique space for political organizing.

Hashtags rhetorically constitute publics in digital space through the organized yet open-ended circulation of texts. For Michael Warner, “a public is the social space created by the reflexive circulation of discourse” (62). The result of such circulation is a consortium of individuals, each of whom is hailed and brought into collectivity as a possible public; this public may then act or react, agitate or resist. It is crucial for the possibility of productive agitation that publics are not formed in advance; their constitution assumes a state of becoming with others.1 Before being called into a public, would-be public-members are likely to be strangers who are then drawn together by networked nodes of commonality.2 Because of a public’s contingent and timely nature, the hailing of strangers and their constitution into a public is liminal, transitional, and transformative.

Social media networks provide unique opportunities for the formation of publics insofar as they make possible the sudden and contingent co-presencing of multiple individuals and/or consortiums across time or space. These networks are organized around nodes of connectivity which forge individuals into collectives based on affinity even absent traditional, institutional organization schemes. The crystallization of many strangers into a digital public is made especially possible by the expansive, global reach of social media. Twitter, in particular, makes easier the process of thinking, speaking, and acting in the world with others because it organizes topics with hashtags (White).

Two rhetorical functions of hashtags are worth addressing at length. First, hashtags function as the coordinating signal of commonality; it is through the hashtag that strangers are organized as latent participants in public conversations with the possibility of activation and transformation by and through the circulating text that follows after the pound (#) sign. As Axel Bruns and Jean E. Burgess suggest, “hashtags are used to bundle together tweets on a unified, common topic . . . [such] that the senders of these messages are directly engaging with one another, and/or with a shared text outside of Twitter itself” (5). Without the means of rhetorically condensing particular nodal points of public conversation, the circulation of digital texts in social media space would fail to bridge the vast temporal and spatial gulfs between users.

Second, hashtags are discursively fungible, exchangeable, or flexible. They must be short enough to allow users to both cite the hashtag and insert their own commentary within Twitter’s 140-character limit (“Using Hashtags on Twitter”). Hashtags must be catchy, repeatable, and abstract enough to invite a huge number of tweets, while simultaneously being clear enough about their referent to ensure conversation remains focused on the topic. They rely on semantic abstraction in order to open up conversation to the public world of strangers.3 The discursive flexibility of the hashtag allows it to bound the scope of digital discourse while simultaneously opening up that discourse to widespread viral circulation. The intelligence of the hashtag as a rhetorical tool of online organizing lies in its ability to invite individual signifying practices while also abstracting those acts of signification for the purposes of public addressivity among strangers.

Hashtags are both promising and dangerous because, by their very nature, they call into being publics whose ideas, membership rosters, and ideologies cannot be determined in advance.4 They organize discourse while concomitantly opening that discourse to the chaos of online circulation. The collectives formed around the hashtag are not only constituted in the initial moment of hashtag dissemination but also in the adaptation, combination, and transformation of hashtags as they are circulated. The very lack of surety that gives hashtags their capacity for rapid circulation and viral uptake by diverse audiences also introduces the conditions of possibility for the formation of publics beyond what was originally intended. The collectively determined, contingent replicability of a circulating hashtag offers a space of freedom for activists who desire to imagine the world otherwise, as well as a strategy for co-option for those who oppose these activist interventions. The publics constituted through the circulation of hashtags enjoy a transformative liminality that mandates chance, risk, and danger.5 In the case studies below, we discuss both the positive and deleterious dividends such risk produced for anti-racist organizers and activists.

#HandsUpDontShoot

In this section, we suggest that the rhetorical force and suasory power of #HandsUpDontShoot can be accounted for through the technical and rhetorical principles and affordances which also lend it its virality as a successful hashtag: its multimodal coordination of digital, visual, and sonic acts of rhetorical dissent; its capacity for mimesis; its ability to articulate between the contingent moment of Michael Brown’s killing and to broader historical patterns of state racism; and its discursive fungibility as a metaphor for racialized state violence.

Sixteen of the twenty-nine eyewitnesses to the Ferguson shooting reported that Officer Wilson shot at Brown when he had his hands up (Santhanam and Dennis). As a result, “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!” became a rallying cry and organizing point for Ferguson protests, as protesters across the globe chanted the slogan and performed the now iconic gesture of putting their hands above their heads (Frisk). Images of these protests circulated widely in social media with the hashtag #HandsUpDontShoot. The #HandsUpDontShoot gesture, chant, and hashtag were used by a number of different groups to protest the shooting and Wilson’s non-indictment, including medical students at the University of Chicago Medical School (PNHP), the St. Louis Rams (“Ram’s Players”), protesters in Grand Central Station (Everett), and a group of congressional staffers (Mother Jones). This list is far from exhaustive (“Trend: #HandsUpDontShoot”), but demonstrates how #HandsUpDontShoot worked mimetically and multimodally—as a text, chant, algorithmic organizational tool, and image—to unite strangers in shared discursive action across space and time.

A powerful rhetorical element of #HandsUpDontShoot was its mimetic capacity—its ability to function simultaneously as a Twitter hashtag and a visual meme. Hashtags themselves are a kind of meme, what Leslie Hahner describes as “a virus-like cultural artifact that proliferates by replication and mutation” (153). For a meme to successfully proliferate, it must both be stable enough to allow for repetition, but flexible enough to allow for mutations in iteration (Hahner 156). #HandsUpDontShoot, as gesture, chant, and image, was publicly intelligible and discursively exchangeable, fixed enough to organize public conversation around the topic of racist police violence, but imaginatively infectious enough to captivate the attention of strangers, inviting its circulation.

#HandsUpDontShoot coordinated the particular eyewitness accounts of Brown’s killing with broader cultural narratives and responses to police brutality. The discursive commutability of the now iconic meme provided anti-racist groups the means to both bear witness to Brown’s killing and simultaneously articulate their rhetorical demands outward from that contingent event to the durable, persistent, and quotidian threat of police violence against black bodies. The algorithmic organization of images of bodies performing resistance were bound together by the hashtag #HandsUpDontShoot, signaling a mimetically mediated act of visibility and solidarity in the geographically dispersed but publicly connected struggles of the #BlackLivesMatter movement in the wake of the Michael Brown shooting. Despite its successes, #HandsUpDontShoot was far from an uncontested rhetorical victory for anti-racist organizers.

#PantsUpDontLoot

The phrase “Pants up, Don’t loot,” a mutation of #HandsUpDontShoot, first appeared as the title of an article in the conservative journal The National Review by Ryan Lovelace (2014). Inspired by Lovelace’s article, Don Alexander, a vociferous Darren Wilson supporter, used social media to raise funds for a billboard emblazoned with the racist slogan in Ferguson, MO (Chasmar). Just as #HandsUpDontShoot became a rallying cry for Ferguson protesters, #PantsUpDontLoot provided a means for the formation of right-wing, racist online publics in response to the Ferguson protests while simultaneously counteracting the narrative of police racism that emerged in the wake of Brown’s killing.

The “PantsUp” half of the hashtag was used to evoke images of black criminality, with sagging pants being a common trope of black youth’s supposed dereliction (Kaba 2010, 2011). The sagging pants trope is a pernicious form of racialized respectability politics; it is a particularly salient enthymeme for the idea that black persons invite their unequal treatment by dressing, acting, speaking, and behaving inappropriately according to the norms of white respectability (Dickson). The “DontLoot” half of the hashtag drew upon a constructed narrative that the Ferguson protesters were violent, self-indulged individuals destroying their community and stealing from local businesses (Basu and Karimi). The circulation of #PantsUpDontLoot increased the hypervisibility of images of blackness as chaos and destruction, and, in so doing, worked to delegitimize the voices of the protesters.6

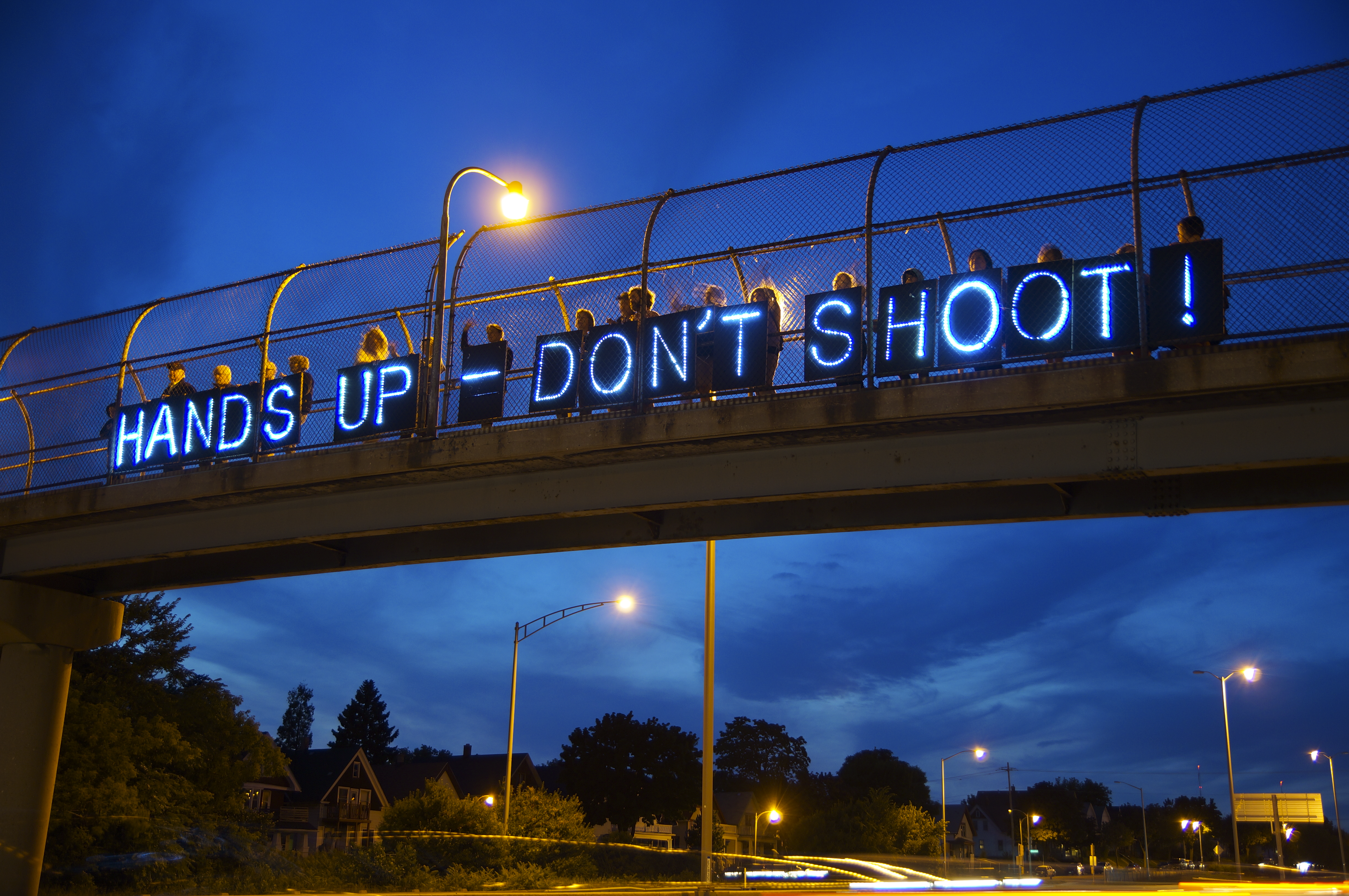

The viral circulation of #PantsUpDontLoot relied both on the highly visible signs of protest organized by #HandsUpDontShoot and modern technology that makes it easy to digitally manipulate visual images. A tweet by Summer Hawkes contains a picture of what appears to be counter-protestors in Ferguson who have erected a lit-up blue sign that says, “Pants Up – Don’t Loot!”

Despite appearing to capture an actual IRL counter-protest, the photograph is actually a digitally manipulated version of a “Hands Up Don’t Shoot!” protest sign by Portland leftist activist group the Overpass Light Brigade (Overpass Light Brigade- PDX). This shows how, as Hahner argues, “[o]nline, visual texts play upon the ambiguity and manipulability of the digital text to drive controversy and contestation” (165). The caption of Hawkes’ tweet, which read “#PantsUpDontLoot sparks 100-700% gun sales in #Ferguson, Clayton, and St. Louis County,” implicitly urged white citizens to arm themselves in response to the protesters.

The characteristics that provided #HandsUpDontShoot its rhetorical potential and organizational power—the hashtag’s capacity for visual mimesis, its capacity for discursive exchange, and its condensation of conversation into blunt but rhetorically persuasive tropes—also lent #PantsUpDontLoot suasory force for racist publics attempting to counteract the rhetorical power of the #BlackLivesMatter protest. #PantsUpDontLoot condensed easily repeatable and overly simplified tropes about black life into a single hashtag, allowing racist publics to gloss over the complexities of deeply entrenched historical racism by focusing on a media spectacle of black dereliction. The circulation of stereotypical images of “thugs” and “looters” amplified highly visible traits in particular historically contingent moments in order to decontextualize the anti-racist struggle and delegitimize people of color as a whole. What, then, are we to make of the possibilities of hashtag activism in the wake of #HandsUpDontShoot and #PantsUpDontLoot?

Conclusion

The rapid and seamless mutation of #HandsUpDontShoot into #PantsUpDontLoot demonstrates that “the rapidity of online distribution and the uptake of highly malleable images . . . allows for what were seemingly discrete frameworks to collide and converge” (Hahner 155). In the instance of #HandsUpDontShoot, we witness the discursive collision between publics attempting to protest state racism and those seeking to discredit the protesters. Whereas the rapid circulation of #HandsUpDontShoot prompted the formation of anti-racist publics and coordinated material practices of protest against the violence of state racism, #PantsUpDontLoot prompted the formation of racist publics and coordinated material practices of violence against black life. These two hashtags suggest the inherent risk involved in organizing publics through hashtags, as the publics constituted through the circulation of hashtags are necessarily collective, contingent, and contested. Anti-racist activists should neither abandon the hashtag nor embrace it as a panacea to the problems of organizing in digital space, but instead must carefully weigh the benefits of rapid connectivity with the likelihood of appropriation.

Given the suasory power of hashtags and their increasing use in organizing protests, we suggest that scholars of visual rhetoric and digital rhetoric attend to the rhetorical nature of technical objects such as the hashtag, especially as they pertain to the construction of anti-racist and reactionary publics. These fields of study are uniquely poised to examine how racially charged visual signifiers are circulated and appropriated in online conversations about state racism, how activists use images and technology to engage in anti-racist political action, and how white supremacist publics rely on the manipulation and rearticulation of those technological tools and visual rhetorical strategies in the defense of state racism. Clarifying the rhetorical potential for hashtags as an organizational tool for both racist and anti-racist publics demonstrates the caution with which protesters must approach the task of organizing online.

Endnotes

- Michael Warner notes that “[p]ublic speech can have great urgency and intimate import. Yet we know that it was addressed not exactly to us but to the strangers we were until the moment we happened to be addressed by it” (57). return

- As Bruce Bimber, Andrew J. Flanagin and Cynthia Stohl argue,“[t]echnologies help people develop collective identities and identify a common complaint or concern” (379). return

- Hashtags’ discursive fungibility relies on what Christian O. Lundberg has described as the “stupidity of the sign,” the ability of signs to serve as a conduit of individual expression while simultaneously sacrificing the particularity of meaning in order to allow strangers to cohere socially around signifying practices. As Lundberg writes, “The practice of being a stranger among other strangers requires that publics act as stupid spaces of abstraction” (134). return

- Warner suggests that publics are generative, “poetic worldmaking” (82). return

- Tracy Tuten and William Angermeier note that “[t]he wise social media user will recognize that unintended outputs . . . are always a part of creation” (71). return

- As Nicole R. Fleetwood argues, “[h]ypervisibility . . . describe[s] . . . the overrepresentation of certain images of blacks and the visual currency of these images in public culture. It simultaneously announces the continual invisibility of blacks as ethical and enfleshed subjects . . . so that blackness remains aligned with negation and decay” (16). return

Works Cited

- Basu, Moni, and Faith Karimi. “Protesters Torch Police Car in Another Tense Night in Ferguson.” CNN. CNN, 26 Nov. 2014. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Bimber, Bruce, Andrew J. Flanagin, and Cynthia Stohl. “Reconceptualizing Collective Action in the Contemporary Media Environment.” Communication 15 (2005): 365-388. Print.

- Bruns, Axel, and Jean E. Burgess. “The Use of Twitter Hashtags in the Formation of Ad Hoc Publics.” Proceedings of the 6th European Consortium for Political Research General Conference, Reykjavik, Iceland. 25-26 Aug. 2011. Web. 1 July 2015.

- Chasmar, Jessica. “Darren Wilson Supporter Fundraises Enough for ‘Pants Up, Don’t Loot’ Billboard in Ferguson.” The Washington Times. The Washington Times, 17 Nov. 2014. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Dickson, James David. “Sagging Pants, the N-word and the Durability of Racism.” The Detroit News: Politics Blog. The Detroit News, 1 Aug. 2013. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Everett, Cristina. @cristinaeverett. “Chants at Grand Central Quickly Went from #ICantBreathe to #HandsUpDontShoot.” 3 Dec. 2014. 7:06 PM. Tweet. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Fleetwood, Nicole R. Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2011. Print.

- Frisk, Adam. “#HandsUpDontShoot Solidarity Rallies Continue across U.S.” Global News. Global News, 21 Aug. 2014. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Hahner, Leslie. “The Riot Kiss: Framing Memes as Visual Argument.” Argumentation and Advocacy 49 (Winter 2013): 151-166. Print.

- Hawkes, Summer. @SummerAnnHawkes. “#PantsUpDontLoot Sparks 100-700% Gun Sales in #Ferguson, Clayton, and St. Louis County…. #tcot.” 19 Nov. 2014. Tweet. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Kaba, Mariame. “Sagging Pants, Criminality, and Prison Clothing.” Prison Culture. 14 Dec. 2010. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- —. “Sagging Pants, Hypercriminalization and School Pushout . . . ” Dignity in Schools. 28 Sept. 2011. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Lundberg, Christian O. Lacan in Public. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P: 2012. Print.

- Mother Jones. @motherjones. “Dozens of Congressional Staffers Just Walked off of their Jobs. This Powerful Photo Shows Why.” 11 Dec. 2014, 12:59 PM. Tweet. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Overpass Light Brigade – PDX. “Hands Up Don’t Shoot – OLB Action.” 18 Aug. 2014. Web. 25. Jan. 2016.

- PNHP. @PHNP. “University of Chicago Medical School #whitecoats4blacklives #BlackLivesMatter #ICantBreathe #HandsUpDontShoot.” 10 Dec. 2014. 11:35 AM. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- “Rams Players Put Hands in Air in Recognition of Ferguson.” NBC Sports. NBC Sports, 30 Nov. 2014. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Santhanam, Laura and Vanessa Dennis. “What Do the Newly Released Witness Statements Tell Us about the Michael Brown Shooting?” PBS Newshour. PBS Newshour, 25 Nov. 2014. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Shirky, Clay. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. New York: Penguin, 2008. Print.

- “Trend: #HandsUpDontShoot – Best of Twitter.” Tag the Bird, n.d. Web. 12 Dec. 2014.

- Tufekci, Zeynep. “Social Media’s Small Positive Role in Human Relationships.” The Atlantic. The Atlantic, 25 Apr. 2012. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

- Tuten, Tracy and William Angermeier. “Before and Beyond the Social Moment of Engagement: Perspectives on the Negative Utilities of Social Media Marketing.” Gestion 2000 30.3 (2013): 69-76. Web. 1 July 2015.

- “Using Hashtags on Twitter.” Twitter Help Center, n.d. Web. 30 Mar. 2015.

- Warner, Michael. “Publics and Counterpublics.” Public Culture 14 (2002): 49-90. Print.

- White, Michele. “How ‘your hands LOOK’ and ‘WHAT THEY CAN DO’: #ManicureMonday, Twitter, and Useful Media.” Feminist Media Histories 1.2 (2015): 4-36. Web. 1 July 2015.

Cover Image Citation: https://www.flickr.com/photos/fuseboxradio/15832150320

James Alexander McVey (

James Alexander McVey ( Heather Suzanne Woods (

Heather Suzanne Woods (