Racist Visual Rhetoric and Images of Trayvon Martin

When Latino1 crime watch volunteer George Zimmerman was finally arrested and charged with second-degree murder for the killing of Trayvon Martin2, an unarmed African American teen, those who had argued for his arrest celebrated a rhetorical victory. But Zimmerman’s subsequent acquittal by a jury of one Latina and five white women sparked celebrations as well as protests calling for the Attorney General to open a civil rights case against him, evidence that the racial issues intertwined in the killing, the arrest, and the verdict remain.3

As an ethical wrong, racism presents a never-ending imperative to speak. Frankie Condon describes this perpetual exigency as “a problem, crisis or dilemma that can and must be addressed through discourse” (25). In other words, while a specific rhetorical moment that creates and is created by rhetoric may arise and pass, racism is an ongoing discourse that both gives rise to and emerges from many rhetorical moments—it is a continuous force requiring continuous opposition. The discourses of racism are as much visual as they are textual and oral; as Judith Butler observes, “The visual field is not neutral to the question of race; it is itself a racial formation” (17). During the debates about arresting George Zimmerman, race and racism thoroughly inflected the visual claims made via his and Martin’s images. The visual racial elements of the entire Trayvon Martin tragedy are beyond this essay’s scope, so I respond here to Condon’s call by examining how the debate surrounding the decision to arrest George Zimmerman was waged through racialized visual discourse focused on depicting Trayvon Martin as one of three tropes: a cherubic black child, a menacing black criminal, or an average teenager.

The cultural embeddedness of seeing is well-established (Berger; Fanon; Fleckenstein; Jay). Whether we see, what we see, and how we see it is determined by tacit cultural conventions and regulation. Kristie Fleckenstein observes that “[a] specific way of seeing, like a specific discourse formation, is objectified and legitimated through the institutionalization of social structures, including architecture, city design, social rites, rituals, myths, and roles serving to define and unify a community” (“Incarnate Word”). Martin Jay, via French film theorist Christian Metz, has used the phrase “scopic regime” to describe this reciprocal relationship between culture and sight.

Power and inequality themselves have long been mediated by visual practices across an array of media (Berger; Butler; Yancy). In racist cultures, a “racially saturated field” (Butler) creates the backdrop for a scopic regime, perpetuating inequities by visually presenting people of color as Other. Zimmerman followed and shot Martin because of the way Martin looked to him, as Other. Mainstream media reinforced that vision both by depicting Martin as an angel in some cases and by depicting him as a threatening thug in others. Media coverage of Martin’s killing and responses to that coverage have been steeped in the visual, depicting a crime about seeing and being seen that extends beyond the actions of victim and perpetrator and out to mainstream culture at large. President Obama framed the event’s visual significance when he observed, “My main message is to the parents of Trayvon Martin. You know, if I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon,”4 directly challenging the racist scopic regime he has confronted throughout his political career. While directed at Martin’s parents as a demonstration of empathy and solidarity, Obama’s message attempts to thwart what George Yancy describes as “the white gaze as a racist socio-epistemic aperture” (14), a way of seeing that creates and is created by a racist reality. Obama’s observation provides an alternate to the vision that pictured Martin as a criminal; the comment reshapes the lens so that one sees a young man who could have become President of the United States rather than a criminal who attacked an innocent crime stopper. Obama’s comment counters the “attributing of violence to the object of violence” (Butler 20), because, as Butler explains, “‘seeing’ and attributing” in cases involving black men can be indissoluble (20). Under the whiteness gaze, Martin rather than Zimmerman was on trial, which meant that bringing Zimmerman to trial required persuading the public and in turn law enforcement officials that Martin had been the victim. Although this strategy succeeded enough to bring Zimmerman to trial, it later failed when most of the jurors concluded and then convinced the dissenting juror that Martin had been the aggressor.

This task of challenging a stereotypical view of Martin often veiled his complete humanity. The earliest extensive coverage of Martin’s killing emerged in Florida news outlets (Coscarelli), many of which juxtaposed two images:

One image is a picture of “fresh-faced” smiling Martin, wearing a red Hollister tee-shirt, which many assumed was taken when he was a young teenager, but which was taken when he was sixteen (Capehart). The Hollister shirt identifies him as a middle-class teen wanting to project a southern California (“SoCal”) identity, associated with ease and openness. Scripps media paired this photo with a 2005 mugshot of a beefy, angry-looking George Zimmerman wearing an orange polo shirt, which many viewers, including Poynter.org, took to be a prison jumpsuit, a juxtaposition that was picked up by hundreds of individual and news blogs. This pairing, because it was featured by a central news outlet, was recirculated by hundreds of other news outlets and blogs, solidifying the contrast between the two men in the popular imagination.

Several conservative websites such as Draw and Strike, as well as Zimmerman’s brother Robert, claimed that Zimmerman’s skin in the mugshot photo had been lightened to help the liberal cause of criminalizing white people (Hing). Following initial coverage of the shooting, the Orlando Sentinel ran a photo of a different-looking Zimmerman: darker skinned, rested, smiling and wearing a suit and tie.

The Sentinel received the photo from an unnamed source, and eventually allowed clients of McClatchy-Tribune news services to use it. In this photo, Zimmerman is a quintessential upstanding, professional middle class man of color. Although it is incontrovertible that the Zimmerman mugshot photo appeared with a range of skin tones, the intent of this variation is less clear. What is clear is that Zimmerman’s race resisted the easy categorization of a racial binary.

While Martin’s race was generally reported as black or African American, Zimmerman’s race in some instances was not reported; in other instances he was described as “Latino”; “Hispanic”; “biracial” or “white Latino.” Zimmerman’s mother is Peruvian and his father is a white American. Initial police reports noted Zimmerman’s race as white. Zimmerman himself avoided the question of his racial identity when he published a website ostensibly designed to raise defense money. Titled “The Real George Zimmerman” superimposed on an American flag backdrop, the site had a “My Race” section, in which Zimmerman did not discuss his race and instead only quoted Thomas Paine, “The world is my country, all mankind are my brethren, and to do good is my religion.” He attempted to place himself outside of racial categories, to position himself as a raceless individual. Amid allegations that his wife had perjured herself during a bond hearing about income produced by the website, Zimmerman’s attorneys had him remove the site before the trial began. Zimmerman’s race, which challenged the dichotomous needs of a racial scopic regime, was as much manipulated as Martin’s image in the debate over Zimmerman’s guilt.

The image of the cherubic African American Martin was reinforced by some of the most popular news outlets in America, including a People magazine cover featuring the Hollister photo along with the headline “Trayvon Martin’s Death: An American Tragedy.” Martin here is an innocent boy, caught in an “American Tragedy,” an allusion to Dreiser’s 1925 novel of class struggle. The article title sanitized the event by using “death” instead of “murder” or “killing” and de-racialized it by describing it as “American,” something that could have happened to someone of any race, which it reinforces with a response from Sybrina Fulton, Martin’s mother: “People want to make this a black and white issue, but I believe that this is about right and wrong. No one should be shot just because someone else thinks they’re suspicious.” The article further attempts to efface the racial discourse through statements by two of Zimmerman’s “African-American” friends affirming his non-racist credentials.

Other People photos, which were also circulated on the Internet, featured a smiling Martin holding a snowboard at a ski resort; riding horses; and holding a laughing baby. These photos depict a happy, middle-class, black child during innocent leisure moments with his family. For the most part, these boyish images are rarely accompanied by the more rebellious images of Martin—photos in which he scowls, blows smoke or extends his middle finger to the camera—photos that Martin used to represent himself on MySpace and that Zimmerman’s supporters have circulated.

Several reasons explain the selectivity of this representation. One is commercial: pathos attached to an innocent, middle-class ethos sells. Pathos, as invoked by the photos, unsettles the whiteness gaze and its assumptions about the Black body: “how dangerous and unruly it is, how unlawful, criminal, and hypersexual it is” (Yancy 3). The “racially saturated field” that Butler identified is confronted with its apparent opposite—the cherubic black child, de-sexualized and neutralized. A martyred child provides a more marketable story is easier to convey than the nuanced complexity of a human teen, who smoked marijuana, chased girls, blustered for the camera and was robbed of his life.

Another is personal. In response to a flood of negative commentary and threatening images of Martin, his father said, “At the end of the day that was our child, and we knew our child and we loved him. And no matter what you try to say about him, [or] how you try to spin his image, or … try to assassinate his character, we know his character, we know his image, and it’s up to us to not let you smear him” (qtd. in Reid). Tracy Martin expresses a family’s desire to control their son’s ethos in the face of image-shaping forces that include the apparent truth-telling of photographic media, along with the web’s circulation powers of speed and scope. Moreover, the absence of a true “delete” button (Mayer-Schoenberger), gives a racist scopic regime additional force because once a particular image is released it remains in circulation forever.

Fearing that white Americans would more likely call for the arrest of a man who had killed an innocent black boy than one who had defended himself against a black gangster, conservative media and Zimmerman’s attorneys placed Martin’s sanitized sainthood on visual trial with counter images. The blog Sad Hill posted “Liberal ‘Mainstream’ Media Releases News Photos of Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman” accompanied by a photo of a black baby labeled “Trayvon Martin” juxtaposed with a color photo of a grimacing science fiction monster labeled “George Zimmerman.”

Photos of Martin exposing a tattoo and wearing gold grillwork in his teeth, taken from his MySpace and Twitter accounts, along with photos of other “Trayvon Martins”–a much older, tattooed and scowling black man, and a teen who was not the murder victim– appeared on conservative blogs and news, as did reports that Martin used a Twitter handle, @no_limit_nigga, that echoed a song by the rappers Kane & Abel. These versions of Martin tapped into a pre-existing white imaginary in which all black men threaten white safety. This imaginary, Cornell West explains, preserves white identity through its ability to efface white class, gender and social conflict: “Without the presence of black people in America, European-Americans would not be ‘white’—they would be only Irish, Italians, Poles, Welsh, and others engaged in class, ethnic and gender struggles over resources and identity” (156)5. A racist scopic regime contributes to the white conflict reduction and displacement by teaching viewers to associate images of blacks with violence and those of whites with peace. Zimmerman confounded the dichotomy, but as either a Latino or “white Latino” he was joined to white racism by being positioned as someone threatened by black violence: someone trying to protect his neighborhood from an encroaching hooded black threat. A legal system that assumes black violence would view any defense against any black male as justifiable.

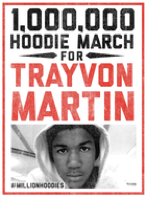

As a powerful counter-narrative to the visual construction of Martin as the aggressor, protestors staged the Million Hoodie March held on March 21 2012, which coincided with a visit to New York made by Martin’s parents, who were making television appearances to campaign for Zimmerman’s arrest. Posters publicizing the event used a recent photo of Martin wearing a hoodie.

This image was not the pre-pubescent boy; it was the teenage Martin, speaking both to justice on an individual level (that is, Zimmerman’s arrest) and the larger, more systemic issue of vision in the dominant myopic culture. By using the image of the older Martin, protesters relied less on pathos to evoke sympathy for a child and more on ethos, appealing to a shared value of justice. The photo was also a way to restore Martin’s ethos, representing him neither as child nor as thug, but as a young man with whom viewers might identify.

The Million Hoodie March inspired protests around the U.S. and in other countries, as an image event that combined visual, spoken and written discourses calling for Zimmerman’s arrest. Million Hoodie March alluded to Zimmerman’s 911 call observing that Martin was wearing a hoodie and looked suspicious, while also invoking one of the most significant recent civil rights actions, the 1995 Million Man March on Washington, aimed at persuading lawmakers and the general public to recognize and re-see African American men and social issues impacting them. Thousands of people of all races, ages and genders wore hoodies in New York’s Union Square, calling out at various moments, “Do I look suspicious?” Adult protestors and babies wore or carried signs asking the same question, which quickly became a social media event, including a hashtag (#millionhoodies), and Tumblr and Facebook pages. At the march and online, people of all races provided autobiographies, documenting their contributions to family, work and community, using words and images to question the idea of “suspicion” and black criminality.

Visual performances combined text and image to shatter a single, myopic lens. The word-image relationship, so central to an image event was less dialectical here than it was disintegrative. Combined with thousands of images of diverse peoples wearing hoodies, the image of Trayvon Martin challenged “[w]hite racist practices [that] construct an iterable conception of the Black body [in which] all Blacks are the same” (Yancy 25-26). The visual effect of live protestors’ photos, along with Internet images, directed viewers in multiple directions to fracture Zimmerman’s claim that Martin looked suspicious. In essence, the individuated photos challenged the whiteness gaze and generalized visual claim that a hoodie connoted guilt and restored Martin’s visual ethos as an innocent individual.

Imagery, Fleckenstein argues, has a kind of duality to it—it is seemingly accessible because “everyone evokes [images]” which gives them a kind of thingness, but she reminds us, “images … are not things. They are relationships that we create” (“Introduction” 8). The images connected to Martin’s killing reveal our relationships to race, justice, and humanity. A starting point for disassembling a racist scopic regime would include a perspective that allowed people to see Martin in the way that Sybrina Martin wanted him remembered “as just an average teenager, just somebody that was struggling through life but nevertheless had a life” (qtd. in Blow).

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Nancy Kendrick, Hyun Kim, and Dana Polanichka of Wheaton College, along with the anonymous reviewers, for their insightful readings of this manuscript’s earlier drafts.

Endnotes

- Zimmerman checked “Hispanic” on his voter registration card, which may be more an indication of the form’s limitations rather than Zimmerman’s self-identification. Neither “Latino” nor “Hispanic” actually refers to a race. I address the contestations over Zimmerman’s race later in the essay. return

- On February 26, 2012, 28-year old Zimmerman driving his SUV through his Sanford, Florida gated community when he called 911 to report “a real suspicious guy” walking around in the rain. He was referring to the seventeen-year-old Martin, who was wearing a hooded sweatshirt on his return from a 7-Eleven and heading back to his father’s girlfriend’s house, where he was staying. The dispatcher told Zimmerman, who was carrying a gun, that he didn’t need to follow Martin, but Zimmerman got out of his car, followed Martin, and the two fought. One of them cried for help before Zimmerman shot and killed Martin, claiming self-defense. Initially, police did not charge Zimmerman with a crime, asserting that he had been within his rights under Florida’s “Stand Your Ground Law,” which permits citizens to use deadly force anywhere if they feel they are endangered. Forty-four days after the shooting, Zimmerman was arrested and charged with second-degree murder. return

- Since Martin’s death two other appallingly similar murders have occurred: in Florida, the shooting death of unarmed African American Jordan Davis by Michael Dunn, who is white, in 2012, and the 2013 killing of unarmed African American Kenisha McBride by Theodore Wafer, who is white, in Michigan. return

- This exploitation applies to other racial minorities, including Asians and, ironically in this instance, Latinos. My thanks to the anonymous reviewer who pointed this out. return

- My essay focuses on the visual images in the case, but it is important to note the larger context of social action that preceded this march. Martin’s parents created a Change.org petition calling for Zimmerman’s arrest; a day later they sued to have the public records on the case released; the NAACP sent a letter to the US Department of Justice requesting that its Community Relations Service review the case. return

Works Cited

- Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin, 1972. Print.

- Blow, Charles M. “Sybrina’s Sorrow.” New York Times 5 June 2013. n. pag. Web. 15 June 2013.

- Butler, Judith. “Endangered/Endangering: Schematic Racism and White Paranoia.” Reading Rodney King, Reading Urban Uprising. Ed. Robert Gooding-Williams. New York: Routledge, 1993. 15-22. Print.

- Capehart, Jonathan. “Playing ‘Games’ with Trayvon Martin’s Image.” Washington Post 6 Feb. 2013. n. pag. Web. 20 June 2013.

- Cates, Brian. “Are Media Outlets Using a Deliberately Lightened Picture of Zimmerman To Make Him Look ‘Whiter’?” Draw and STRIKE! n.p., 29 Mar. 2012. Web. 23 June 2013.

- Condon, Frankie. I Hope I Join the Band: Narrative, Affiliation, and Antiracist Rhetoric. Logan: Utah State UP, 2012. Print.

- Coscarelli, Joe. “The Killing of Trayvon Martin Is Now a National News Story.” New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC, 19 Mar. 2012: n. pag. Web. 20 June 2013.

- Currier, Cora. “The 24 States That Have Sweeping Self-Defense Laws Just Like Florida’s.” Pro Publica. n.p, 22 Mar. 2012. Web. 20 June 2013.

- Fanon, Frantz. “The Fact of Blackness.” Black Skin, White Masks. Trans. Charles Lam Markmann. New York: Grove P, 1967. 109-40. Print.

- Fleckenstien, Kristie. Introduction. “Teaching Vision: the Importance of Imagery in Reading and Writing.” Language & Image in the Reading-Writing Classroom: Teaching Vision. Ed. Kristine Fleckenstein, Linda T. Calendrillo, and Demetrice A. Worley. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002. Print.

- Fleckenstein, Kristine. “Incarnate Word: Verbal Image, Body Image, and the Rhetorical Authority of Saint Catherine of Siena.” Enculturation 6.2 (2009). n. pag. Web. 25 June 2013.

- Hing, Julianne. “The Curious Case of George Zimmerman’s Race.” Colorlines. Race Forward: The Center for Racial Justice Innovation, 22 July 2103. Web. 24 July 2013.

- Jay, Martin. “Scopic Regimes of Modernity.” Vision and Visuality. Ed. Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay P, 1988. 3-23. Print.

- Mayer-Schönberger, Viktor. Delete: The Virtue of Forgetting in the Digital Age. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2009. Print.

- “Newt Gingrich: Obama’s Trayvon Martin Statement ‘Disgraceful.’” The Huffington Post 23 Mar. 2012, U.S. ed.: n. pag. Web. 22 July 2013.

- Online Sunshine. “The 2012 Florida Statutes.” 776.013. Web.

- Reid, Joy-Ann. “Trayvon Martin’s Father, Mother Fight for His Image.” The Grio. MSNBC, 16 June 2013. Web. 25 July 2013.

- Sad Hill. “Breaking News: Liberal, ‘Mainstream’ Media Releases New Photos of Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman.” Sad Hill News. Sad Hill News, 27 Mar. 2012. Web. 25 July 2013.

- West, Cornell. Race Matters. New York: Vintage, 1993. Print.

- Yancy, George. Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. Print.

- Yoos, George. “How Pictures Lie.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 24.1-2 (Winter/Spring 1994): 107-119. Print.

Lisa Lebduska is associate professor of English at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, where she teaches various writing courses and directs a WAC-centered college writing program. Focused on exploring the teaching of composition within social and digital contexts, her work has appeared in such publications as WPA Journal, College Composition and Communication, the Writing Center Journal, and Technological Ecologies and Sustainability: Methods, Modes, and Assessment.

Lisa Lebduska is associate professor of English at Wheaton College in Massachusetts, where she teaches various writing courses and directs a WAC-centered college writing program. Focused on exploring the teaching of composition within social and digital contexts, her work has appeared in such publications as WPA Journal, College Composition and Communication, the Writing Center Journal, and Technological Ecologies and Sustainability: Methods, Modes, and Assessment.