Interview: Transplant Deliberations and Patient Advocacy

For this issue, we interviewed Melissa Christian, RN, BSN, CCTC.1 We chose to interview a working medical professional for this issue for several reasons. First, this special issue contains scholarship from rhetoricians studying health and medical discourse. To provide a balance, we thought it was important and potentially useful to include the perspective of someone working in the medical field. Secondly, many medical rhetoricians seek to answer the question: how can rhetorical research be used by those working in medicine? We asked Melissa how medical rhetoricians could contribute to professionals’ ability to communicate effectively. As a keen communicator, Melissa provided insight into how rhetoricians might advance medical communication praxis and research.

Melissa is the Advanced Heart Failure Coordinator at the Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, NE. As a self-described jack-of-all-trades, Melissa coordinates the medical and social needs for cardiac transplant patients, serving as the primary contact for transplant patients and as a patient advocate during transplant team meetings. The transplant team includes three heart failure/transplant cardiologists, four nurse coordinators, two cardiac transplant surgeons, three cardiothoracic surgeons, procurement surgeons, secretary staff, a transplant social worker, three transplant financial counselors, two transplant psychologists, a transplant pharmacist, and a transplant nutritionist. Working in both a clinical and hospital setting, the transplant team affects all aspects of patient care.

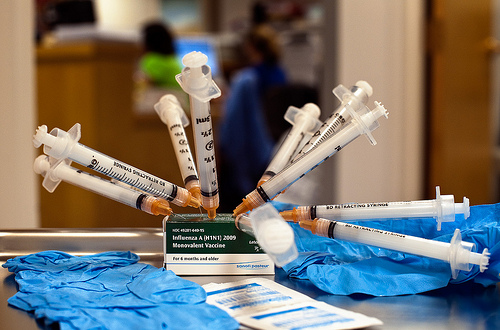

Cardiac transplantation is one of the most highly regulated procedures in medicine. When coordinating a transplant patient’s care, the team monitors a patient’s overall health, heart failure symptoms, and laboratory work. Using protocols, the team fine-tunes patients’ medications with physicians to prevent hospital admissions and improve patients’ quality of life. Educating the patient and their family is key; during all phases of the transplant process, the team informs patients and families about medication regimens and the symptoms that indicate worsening heart failure, infection, and rejection post-transplant.

Our Annotated Bibliography Editor, Elizabeth Angeli, conducted the interview with contributions from Allen Brizee, Bruce Prenosil, and Joshua Prenosil.

Q: Could you overview the timeline during a typical case you work from beginning to end?

MC: Typically, another referring physician will call us with a patient that’s either inpatient critically ill or is in the outpatient setting, and they’ll notify [the] coordinators that there’s nothing else they can do for this patient. We call the patient ourselves individually, try to screen them over the phone, evaluate their history. We’ll try to get a feel of their dynamics, kind of what they want, is this something that they want to go through. Then we send out a packet of written information, including our consent, that explains how patients qualify for cardiac transplant, or even if they don’t qualify, but in the same note let them know that . . . we’re experts in this stage heart failure, but we also give them backup—I like to say, “We give you the backup to the backup to the backup plan.”

In an outpatient setting they [patients] come into our clinic and they meet with our transplant cardiologist as well as us [nurses], and we’re kind of assigned to that patient. The doctor assesses the patient, they look at all their records, and then they decide at that point what would be the best treatment option for them, whether it be medical treatment, surgical treatment, or to go through a cardiac transplant evaluation.

When they [patients] go through the cardiac transplant evaluation, we usually prefer to do that on an outpatient setting—it’s stressful enough to be admitted—and we have two administrative assistants that help us schedule that, and the evaluation includes many blood [tests and] ultrasounds. We make sure they’re “as healthy as possible” going into this to make sure, by us giving them a new heart, we’re not going to make something worse. That testing is to make sure they’re [a] candidate, outside of their heart, to go through this process.

Once they go through this process, the transplant selection committee meets—we usually meet every Friday and then on an as-needed basis—and then all members of that team that touches that patient discuss the patient, look at their evaluation psychologically, socially, to see what candidates they are for that.

If they’re not candidates, or if they are, then a nurse coordinator, whoever seems to know that patient the best and has an established relationship with them, will notify the patient of the decision. If the decision is to list them, then we’ll list them electronically in a national database for a heart. We explain that process to them via over the phone or in person, explain that listing process, the surgical process, and then exchange contact information to get a hold of us [nurses] 24/7. That’s key to give them, “Hey, we are your contact person, be it two o’clock in the morning, Saturday, Sunday, any time of day.” And then we follow them based on their condition, usually every three months or every six months and sometimes monthly, while they’re waiting for their heart, to make sure that medically they continue to be stable.

On the inpatient setting we do the same thing; unfortunately, it’s always emergent. Sometimes they’re already on balloon pumps or what we call ECMO (http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1818617-overview), which is like bypass outside of the operation room, and those are obviously more critical, and then we kind of fast-track those evaluations and try to meet on an as-needed basis sooner than later. Post-listing, most patients are on IV medications to keep their heart going longer, to give them an opportunity to get a heart, and then they have weekly labs and continued follow-up appointments that we are present with, and we monitor their lab results in the outpatient setting.

Once they do get that heart, we do watch them very closely. They have scheduled procedures that are laid out with them in their heart transplant education binders, like a book full of information. We see them weekly for a month, and then every two weeks for two months, then monthly until six months, then usually every couple months up to a year, and then on an as-needed basis. Most of our patients go home with home health nurses; they’re our eyes in the field, and we specifically try to use companies that are experts in heart failure and transplant that watch them also.

Q: Has a patient ever disagreed with a transplant decision that the team has come to?

MC: Absolutely, especially if they’re denied for medical reasons or psychological reasons. I think those are the toughest ones, when the social and psychological team is like, “These patients will not be able to handle a transplant. They do not have the skills or the coping tools to take care of this.” We’ve recently denied somebody with a personality disorder and that was very tough. We do always offer people second opinions.

Q: How did you learn specific communication skills for working with patients and the transplant team?

MC: Communication skills start in nursing school. Obviously, in nursing school they teach you how to communicate with patients. The best communicators are the ones that are the best listeners also. That’s why you find nursing staff typically are the gateway to specific information for patients. For transplant coordination as well as heart failure I think we look at it as a family. To better take care of them, we really need to get to know them personally, on an individual level, not just medically, based on their diagnosis. The family dynamics, too, is always key. My best opportunity is learning from the patient, have them teach me how they like to learn.

Continuing to allow them [patients] to be empowered with their own medical care is key, and getting to know them to see what triggers them to take care of their own needs is huge. You really need to keep them empowered to care for themselves, and to have some kind of control over their level of care is key. When you take away empowerment from nurses, from physicians, I think that’s when you see the communication breakdown.

When you take away individual rights and say, “This is what you’re gonna do,” that’s not a way to communicate. I just did a heart transplant evaluation emergently here on a Sunday night. I got called in—and [all] coordinators also take calls for the patients also, 24/7. But I got called in, and this young 35-year-old just had a catastrophic heart attack with a wife that is a paraplegic from a car wreck catastrophically six months ago. And that was key for me walking into the—they’ve already had something catastrophic happen. The key is just you have to sit down and [they] have to tell you their story before you just chime in and say, “You know, I apologize, but unfortunately, you’re going to die unless you get a heart transplant.” That’s not the way to communicate. If you start with that, you’re going to shut down—the wall is up, no one is going to communicate with you.

Q: Could you describe the role that writing plays in your work?

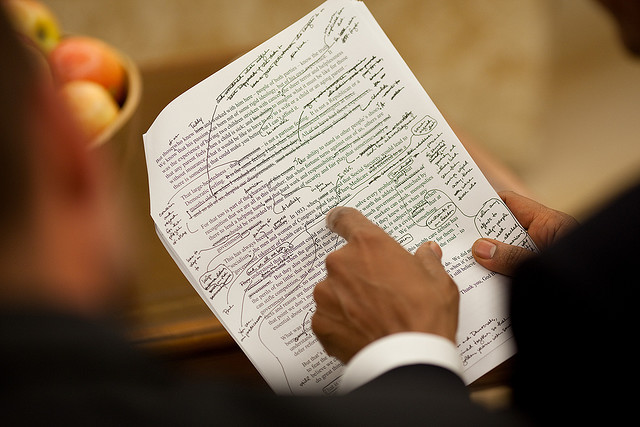

MC: That is something we’re continuing to work on is the writing, but we do have specific heart transplant education packets as well as consents mandated by Medicare that patients must get. What level of writing to give the patients is always an issue. When we developed our heart transplant education binder, we worked instrumentally with the nursing education department at Nebraska Medical Center to get that put in layman’s terms.

We seem to talk above the level of communication that people need quite often. So it’s continually a challenge. That’s a huge deficiency in medical literature, medical knowledge: just putting that information in layman’s terms . . . [and using] appropriate pictures. Research shows how [many] pictures people would like. That’s a continual challenge.

The writing role is more open dialogue between provider to provider and direct communication. All the providers are instructed they need to dictate notes in the system to communicate, as well as [in] an area to chart with short notes. Reading each other’s notes can leave out a lot of the other instances, the other impacts that the patients need addressed or other issues. I would say the people that are probably the best at writing, I notice, would be the social worker and psychologist. Because that’s their focus is that whole system, that whole-body approach. They do have templates, and although templates come with disadvantages, the psychologist as well as social work[ers] definitely hit all those points. Obviously, the medical physicians touch on those, too, but mostly it’s just the medical version of it. So written communication is just two people reading each other’s notes electronically.

With the new age of Medicare reform, everything is going computerized, so everybody has access to each other’s records. Technical people such as surgeons and physicians will keep up with each other’s notes when communicating. The constant theme I see is, why can’t people just pick up the phone and communicate? I think people still prefer verbal communication.

For example, I think weekly meetings are always a great idea for teams to evaluate your current patient load, inpatient and outpatient, and discuss, “Hey, what’s going on with these individuals? How can we improve their care, and what needs do they need?” That’s definitely lacking because you’re unable to do that through written communication.

Q: What goals do you have when communicating with patients and their families, particularly in light of the fear that may surround the transplant?

MC: The biggest goal is to understand the impact that this [communication] leaves. When you blindside them [patients] with this awful information [of needing a transplant], human beings, as a way of protecting yourselves, we shut down and don’t really hear things and that is the key when you communicate. We provide written information after we go through the verbal information. It needs to be a combination because the written kind of reinforces what you said verbally, but when they hear heart transplant, it’s fear; it takes their breath away, literally, because their mortality is thrown in their face. We do reinforce with a written tool so they can take that home to read it by themselves and to go over those, just to help process that. Then we encourage them to take notes, reading that written information, so we can follow up on that the next encounter we have, which we try to follow up the next day.

Q: Do these goals shift when communicating with physicians and nurses?

MC: Absolutely. Our job as nurses is to be patient advocates. I always think the most important job is to represent that patient. Not that [physicians] are not patient advocates, but they’re given a disease, they diagnose the patient, and they know medically what the best option for them is, medically or surgically, but then that may not be the best option for the patient, especially if the patient doesn’t want to go down that path. Nurses have a more holistic approach because they are trained to be patient advocates.

The continual meeting and keeping that open dialogue with all those emotions, all their [patients’] emotions and what they’re going through is key, as well as supporting family members. Typically we don’t do a good job of that and offering other support groups—we have a monthly support group—and as well as meeting with other family members. I love when spouses can meet spouses of transplant candidates. I think that’s huge because what they experience is different from the patients themselves.

Q: Keeping in mind that some of our readers are medical communication specialists, if you had all the needed time and money available to you, what solutions would help overcome the communication challenges that you face?

MC: I think the biggest thing is getting measurable tools. There are a lot of measurable tools out there for patient education, but something more streamlined [is needed]. I know we’re in the age of electronic, but something where you can streamline patient education . . . [and] clinic visits, as well as remotely measurable things such as medication status. We already have medication pill boxes to make sure, electronically, patients are taking their pills but some kind of electronic documentation, some tool, some streamlined tool that people with the same disease processes can use, and collect data on how we can communicate more. As well as some kind of a tool to touch base on their emotional well-being, too. That and some kind of open dialogue. A lot of the tools have yes-or-no questions.

It’s such a key to have a relationship with your patient—it’s so they trust you. They have trust in your team and they have trust to communicate with you—kind of tear down those barriers, tear down the wall that can be put up when patients feel fearful communicating with their medical team.

Q: Is there anything that you hope communication scholars examine or study?

MC: With the age of electronic information, I feel that definitely from a nursing perspective, we’re getting pulled away from good old-fashioned patient care. Everything is electronic and everything is about quality improvement and data collection. I understand those are very important. But with cutbacks with Medicare reimbursement, I feel that that good old bedside nursing is getting lost in the shuffle with modern technology. I want to make sure patients are still treated like human beings. Although electronic information data collection is crucial, you miss that part of getting to know your patient and becoming the best patient advocate possible.

Endnotes

- We have edited the interview transcript for length, readability, and clarity. return