“The People are the Plague”: Rhetorics of Blame During COVID-19

In June 2020, as the nation rose up against unjust police killings of Black Americans, libertarian commentator George F. Will penned an Op-Ed for the Washington Post. In it, he identified what he termed one of the country’s “gravest problems.” “Much education now spreads the disease that education should cure,” he wrote, “the disease of repudiating, without understanding, the national principles that could pull the nation toward its noble aspirations. The result is barbarism.” In Will’s analysis, single mothers, educators, BIPOC, and young Americans are violent outsiders responsible for civil unrest and injustice. Structures of power behind “national principles” that codify inequity simply do not exist.

That same month, lacking federal regulations, states began ending unemployment benefits and lifting COVID-19 restrictions on businesses. Ignoring top public health experts’ pleas to reconsider premature “reopening,” leaders called on Americans to return to normalcy amid a highly contagious COVID-19 outbreak that had already killed more than 100,000. “We all know how to do this,” Missouri Governor Mike Parson told The Daily Journal. “It is up to us to take responsibility for our own actions” (Jones). Governor Parson’s response isn’t isolated—he is following the nation’s call to get back to normal and positioning individuals as responsible for their own safety.

In both of these statements, we see a rhetoric of blame that shifts focus away from social structures and toward blaming individuals for social problems. This rhetoric has a long history, but in a COVID-19 world, it comes together as a by-product of a rhetorical process called “panopticonning.”

In Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault explained the most effective form of imprisonment and, from this, social control, as a system subjecting individuals to constant surveillance and collective distrust. In this, he references the “Panopticon” prison in which prisoners are held in a ring of cells circling a central tower with guards who can not be seen but who might be watching. Rather than feeling controlled by one source, people’s exposure to both the powerful guards and to one another causes them to always fear punishment and to self-regulate, enlisting in self-policing that maintains hierarchical structures of power.

Building upon Foucault, panopticonning entails socially-affirmed self-policing that channels accountability away from those responsible for inequity within capitalism. To do so, panopticonning affirms discourses in neoliberal America that ignore structural oppression by identifying common people as the problem. One place where it is quite visible right now is in the COVID-19 pandemic, which is the focus of our inquiry.

Panopticonning rhetoric protects unaccountably oppressive systems by locating risk and responsibility in marginalized people who disproportionately experience disinvestment and punishment in a neoliberal capitalist world, one that operates on the idea that “human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade” (Harvey 2). As a rhetorical process, panopticonning is accomplished through sharing on social media in order to advance dominant discourses regarding COVID-19 responsibility.

Attention to such discourses provides a unique opportunity for rhetoricians to critically examine how social media visibility assists wider cultural practices using language to organize society and mediate power. Our analysis of the rhetorical process of panopticonning adds to existing scholarship on how neoliberal discourse operates and shapes life in democratic societies (e.g., Brown; Riedner; Rushing Daniel), with a particular focus on the role of social media in that process.

From May through July 2020, we collected several hundred images shared on Facebook depicting blame for US Covid-spread. Across these posts, we identified recurring patterns of blame accomplished through two rhetorical devices: attenuation and augmentation. We found two themes in these patterns of blame: individualizing social unsafety and identifying Americans as outsiders. In this article, we explain the processes of panopticonning and provide examples of the two discourses of blame that result from panopticonning in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Social Attenuation and Social Augmentation

Foucault conceptualized discourses as combining both words and actions (Archeology). Created by social institutions with power and means of communication, discourses are disseminated as knowledge that subtly affirms certain messages, meanings, and understandings of reality over others. Discourses can be contested, but dominant discourses lay claim to truth and normalcy in ways that cast opposing views as marginal, often refuting alternate knowledge or denying its very existence.

Through social attenuation, certain information that is unflattering to those in power is systematically downplayed and denied in dominant discourses. For example, geographer and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore states that the past 40 years have been marked by widening economic inequality in the US accompanied by “organized abandonment,” advancing neoliberal logics rather than systems of care that keep “communities together with adequate income, clean water, reasonable air, reliable shelter, and transportation and communication infrastructure.” Within systems that force both risk and blame on individuals, the few opportunities availed to people commonly provide support to the carceral state, eliminating chances to believe in more just realities.

Through social attenuation, the nation’s systemic disinvestment in public well-being—particularly in marginalized communities—receives little social corroboration and notice even amid decades of material evidence, long before COVID-19, ranging in form from school budgets to corporate tax cuts, as well as soaring prison and poverty rates, healthcare costs, and a lack of access to stable employment.

When considering responsibility for the spread of the pandemic in 2020, social attenuation diminishes attention given to the US administration’s decision to diverge from other nations in not issuing national shelter-in-place or masking regulations and, instead, leaving containment decisions to state and local officials. Attenuation weakened consistent focus on political partisanship established around adherence to national Center for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines. Social attenuation helped focus attention away from policies and practices that withheld personal protective equipment, testing supplies, and financial support from communities across the nation, disproportionately harming BIPOC.

Simultaneously, certain discourses blaming individuals and absolving systems are more prevalent in offering explanations about who is responsible for the spread of COVID-19. They are also privileged in other ways, as systemic supports equip them to gain attention and drown out opposing perspectives, making them more likely to be believed. This occurs through social augmentation. In augmentation, discourses are made more commonplace as they receive social vetting and affirmation by official sources, adding power to the message, and increasing its credibility, trust, and attention as it gains prevalence. For example, in June 2020, psychologist Laurence Steinberg wrote an Op-Ed in The New York Times warning of dire COVID-19 threats to the American public. He identified as the source of these threats college students who promise to exercise “poor self control” when schools reopen in fall, ignoring the US policies and practices recklessly forcing people unsafely into an uncontained pandemic. Through social augmentation, Steinberg’s message about reckless youth gains credibility from appearing in mainstream newspapers as official knowledge.

The social processes of panopticonning are technologies of public relations employed within and beyond the pandemic. Indeed, born as “propaganda,” the field of public relations enlists cultural outlets to subtly augment and attenuate language in support of those seeking to organize society and profit from products, ideologies, and private interests (Arendt; Bernays).

Panopticonning on Social Media

Social media provide faceless mouthpieces for discourses of blame. Research documents Americans using social media to try to gain involvement, information, and control they are denied offline (Rickman), and that the writing people do on social media is a crucial part of contemporary identity formation and management (Babb; Buck). But online spaces exist as a product of offline hierarchies embedded in programmers, policy, practices, and profit motives that create systems within these logics. Like any technology, social media platforms are not neutral (Gruwell) and, while online spaces offer emancipatory promises, they ultimately serve hegemonic interests (Fuchs; Tufekci).

Facebook is the primary source of news for American adults (Shearer and Grieco), but they are allowed to define themselves as a platform—a space simply aggregating information—rather than as a media publisher, denying responsibility for content they host but also curate, provide, and actively promote. In March 2020, a reporter posed as the “Self Preservation Society” in an attempt to run seven Facebook ads with overt misinformation about COVID-19, including those that stated that people under 30 were safe to ignore social distancing and advised virus prevention through daily doses of bleach (Waddell). All were accepted. Since then, Facebook has made modifications to its policies by banning individual accounts and adding warnings about certain misinformation to particular kinds of posts; however, as a technology of trenchant infrastructures of social control attempting to atomize systemic inequities, panopticonning exists well beyond such solutions. For example, Facebook’s advertising-based business model rewards the company with profits for surreptitiously spreading demagoguery and lies. In April 2021, The Guardian reported that, as a result, Facebook’s “platform is being used to manipulate political discourse around the world” (Wong and Ellis-Petersen).

This adds to previous investigations (e.g., Horowitz and Seetharaman; Vaidhyanathan) finding Facebook welcoming manipulation into their community and promising public protections while denying their own power by “rhetorically positioning users on the same plane as would-be content exploiters” (Hoffman et al. 214). In this, social media help to extend the reach and credibility of dominant discourses.

Panopticonning: Othering Individuals as the Source of Social Unsafety

The impact of panopticonning on social media is that it takes away attention from powerful people who are creating unsafe conditions and puts focus on what is framed as marginalized people’s untrustworthiness, augmenting stories told in other parts of US society. A dominant theme in the images we analyzed is that they ignore the patchwork approach to state closures and reopenings, and the past federal government leadership’s refusal to inform the country about the deadly pandemic while delaying ordering and delivery of essential medical supplies and denying support for common people (Levy; Allen, et al.). Instead, these posts center upon the American people as the main threat to public safety by individualizing the source of social unsafety and identifying Americans as outsiders.

Individualizing the Source of Social Unsafety

Panopticonning posts resulted from the policing of individual actions. In doing so, they specifically pointed out others in shared mainstream news stories who did not appear to be following physical distancing and masking rules. However, states and individual regions varied immensely in their requirements around masking and commercial operations (Lee et al.).

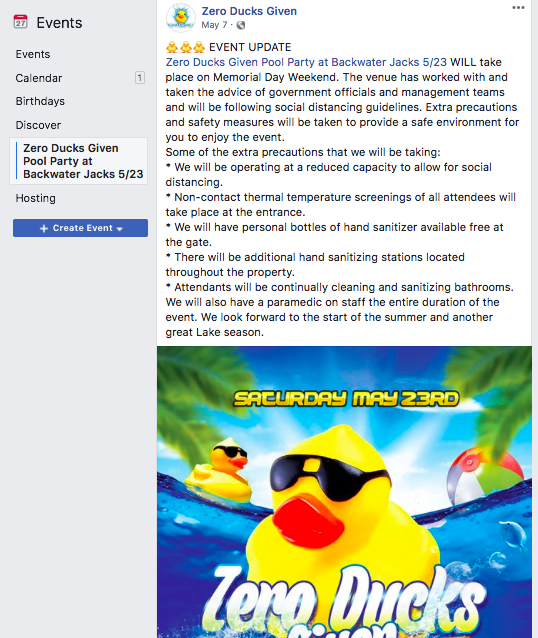

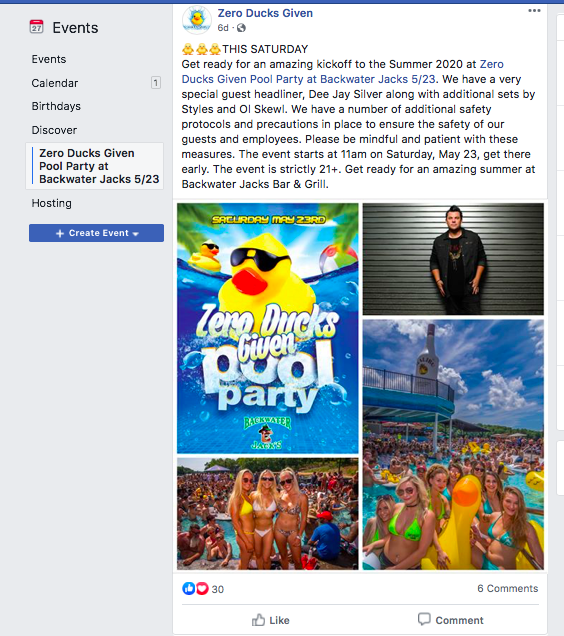

Regional regulatory variations were not clarified in posts that appeared on social media, causing actions to be misrepresented in ways that cast individuals (rather than systems) as reckless and irresponsible. One prominent example cited is Missouri. Missouri began shelter-in-place laws in late March 2020 and ended them on May 15, leading to many attending gatherings on Memorial Day weekend with explicit, if ill-advised, state approval in the Lake of the Ozarks region. Backwater Jack’s bar in Osage Beach hosted a “Zero Ducks Given” reopening event promising rambunctious, pool-party fun with safety measures to ensure public health, such as limited admittance, social distancing, fever screening, and heightened sanitation. Their invitation featured photos of happy people crowded in their pool bar (see figures 1 and 2).

The news stories that appeared about the Lake of the Ozarks region, and numerous other news stories about summer gatherings, augmented and affirmed the notion that the American people are the main reason we are unsafe and unprotected within this pandemic based on their poor individual choices, reckless behavior, and irresponsibility (see figure 3).

Just as rules are broken in other realms, some people certainly eschewed compliance. However, the issue here is the eagerness, in panopticonning posts on social media, to harshly judge other individuals as the source of the spread of COVID-19, and to frame public health as just a personal choice rather than a product of wider social, political, and economic contexts.

Identifying Americans as Outsiders

In addition to placing blame on individuals for systemic failures causing the spread of COVID-19, panopticonning posts used fear, disgust, and anger to demonize, dehumanize, and “other” vulnerable populations in the US. As part of this “outsider” framing, many posts located responsibility for public health safety within the pandemic upon youth, BIPOC, LGBTQ+ people, and other marginalized people in America.

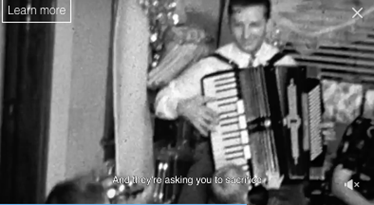

A Facebook-shared video from May 2020 moves between still photos and grainy video as it documents specific events from the US’s past. Behind the visuals, a narrator states, “The generation that stormed the beaches, and tightened their belts. The generation that marched for all our rights, drilled under desks, and bled in the jungle. These generations that sacrificed so much are the most at risk now. And they are asking you to sacrifice” (see figures 4-9).

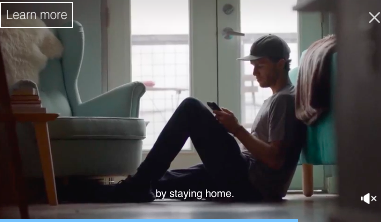

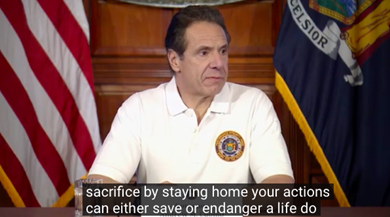

The video moves from clips from the past to a young man in a baseball cap doing no more than poking casually at his phone while surrounded by comfort. The narrator continues: “By staying home.” The video closes by letting the viewer know it was created by the group Partnership for New York City (see figures 10-13).

This video was, in fact, created by many whose actions can either “save or endanger a life.” The mom-and-pop-sounding Partnership for New York City actually consists of 306 multinational corporations. This lecture about the need to “do your part” to contribute to the collective health of America is coming from these corporations, even as they abdicate their own responsibility. Instead, they tell us to blame “irresponsible” American youth, despite the fact that young people struggle from decades of structural dismantlement of public education, social services, public health, civil liberties, and labor rights, and face further punitive, austerity-based policy changes coming in response to the recession. Here, like Steinberg’s Op-Ed about selfish college students, the American youth are held responsible for the impact of the pandemic that they did not cause.

There is a similar move in panopticonning posts that appeared about the crowded Christopher Street Pier in New York City near the Stonewall Inn and National Monument to LGBTQ+ rights. The pier is a long-time gathering and cruising space, and is home to many LGBTQ+ homeless youth (see figure 14).

In May 2020, as the US administration denied the severity of COVID-19 and refused federal lockdown regulations, images that circulated on Facebook identified people gathered at the pier as spreading disease. When considered within this historically queer space, these posts extend rhetorical tropes that portray queer Americans as inherent disease spreaders, which, as Moguel et al. remind us, “is not separate from, but incorporates, strengthens, and expands disease-spreader representations” of other marginalized people (36).

The Human Rights Campaign Foundation finds LGBTQ+ people more likely than straight and cisgender people to work in US industries most impacted by COVID-19. Yet here, the pandemic is positioned as being spread only by the individual actions of the people gathered in this space. Panopticonning augments cultural narratives that name marginalized Americans as the dangerous, outside threat causing COVID-19 risk.

Conclusion

In their discourse analysis of racially-profiling campus crime alert messages, Pantelides, Mueller, and Green find embedded rhetorics of individual responsibility undermining goals of community safety. “[E]liciting unchecked and unexamined vigilance, fear, and anxiety does not keep us safe,” they write. Instead, such practices spread distrust of already vulnerable marginalized populations.

In a COVID-19 world, we need people to wear masks and socially distance in order to be safe, but, by definition, public health exists beyond the individual. The CDC, “our country’s premier public health agency,” states that “public health is the science of protecting and improving the health of people and their communities.” Public health is a communal norm-shaping effort that is undermined when guidance and expertise are denied or intentionally sabotaged in order to shift blame to individuals.

Blaming marginalized US populations for structural failures forces risk on common people burdened from historic disinvestment. Panopticonning rhetoric operates in service to hegemonic efforts, utilizing self-policing within highly-visible social media to augment dominant neoliberal discourses blaming individuals for COVID-19 risk. This normalizes rhetorics of personal responsibility that maintain social division while protecting logics that render individuals—rather than deregulatory systems valuing privatizing policies and punitive practices—deviant and destructive. As a rhetorical process, panopticonning assists in organizing social relations and mediating power, manufacturing consent to punitive systems of social control as part of everyday American life.

In this particularly overwhelming moment, rhetoricians can spotlight how language constructs and shapes our realities in ways that affirm powerlessness, which is a sign of panopticonning’s effectiveness. Ignoring barbarian profiteering and focusing, instead, on individual culpability weaponizes normalized cultural decorum as a rhetorical tactic of neoliberal power within the carceral state (Blow). In the classroom and in the public sphere, rhetoricians are uniquely positioned to interrogate and bring attention to realities that are silenced, to narratives that are emphasized, and to structures that codify and disseminate understandings in service of coercive systems that rely upon marginalized people routinely seeing, distrusting, and blaming only themselves.

Works Cited

Allen, Jonathan, et al. “Want a Mask Contract or Some Ventilators? A White House Connection Helps.” NBC News, 24 April 2020, www.nbcnews.com/politics/white-house/political-influence-skews-trump-s-coronavirus-response-n1191236. Accessed 29 July 2020.

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Meridian Books, 1966.

Babb, Jacob. “Networking in the Moment: Social Media, Digital Identity, and Networked Publics.” Harlot: A Revealing Look at the Arts of Persuasion, no. 15, 2016. harlotofthearts.org/index.php/harlot/article/view/327/190. Accessed 06 August 2020.

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. Ig Publishing, 2005.

Blow, Charles. “Rage is the Only Language I Have Left.” The New York Times, 14 April 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/14/opinion/us-police-killings.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Zone Books, 2015.

Buck, Amber. “Examining Digital Literacy Practices on Social Network Sites.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 47, no. 1, 2012, pp. 9-38.

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. Pantheon, 1972.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Random House, 1977.

Fuchs, Christian. Social Media: A Critical Introduction. SAGE, 2013.

Gabbatt, Adam. “Thousands of Americans Backed by Rightwing Donors Gear Up for Protests.” The Guardian, 19 April 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/18/coronavirus-americans-protest-stay-at-home. Accessed 26 March 2021.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Interviewed by Jeremy Scahill. “Ruth Wilson Gilmore Makes the Case for Abolition.” The Intercept, 10 June 2020, theintercept.com/2020/06/10/ruth-wilson-gilmore-makes-the-case-for-abolition/. Accessed 25 July 2020.

Gruwell, Leigh. “Constructing Research, Constructing the Platform: Algorithms and the Rhetoricity of Social Media Research.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, vol. 6, no. 3, 2018. www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/constructing-research-constructing-the-platform-algorithms-and-the-rhetoricity-of-social-media-research/. Accessed 30 July 2020.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Hoffmann, Anna Lauren, et al. “’Making the World More Open and Connected’: Mark Zuckerberg and the Discursive Construction of Facebook and Its Users.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 1, 2018, pp. 199-218.

Horowitz, Jeff, and Deepa Seetharaman. “Facebook Executives Shut Down Efforts to Make the Site Less Divisive.” The Wall Street Journal, 26 May 2020, www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-knows-it-encourages-division-top-executives-nixed-solutions-11590507499./ Accessed 1 Aug. 2020.

Jones, Kelli R. “Governor Parson Announces Missouri Fully Reopens, Enters Phase 2 of Recovery Plan.” The Daily Journal, 17 June 2020, dailyjournalonline.com/community/democrat-news/governor-parson-announces-missouri-fully-reopens-enters-phase-2-of-recovery-plan/article_34e124f9-c524-572f-a5ad-abeafbdedd6c.html. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Lee, Jasmine C., et al. “See How All 50 States Are Reopening (and Closing Again).” The New York Times, 24 July 2020, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/states-reopen-map-coronavirus.html. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Levy, Pema. “Trump is Weaponizing the Nice Things He Forced Governors to Say About Him.” Mother Jones, 30 April 2020, www.motherjones.com/2020-elections/2020/04/trump-is-weaponizing-the-nice-things-he-forced-democratic-governors-to-say-about-him/. Accessed 1 August 2020.

Mogul, Joey, et al. Queer (In)Justice: The Criminalization of LGBT People in the United States. Beacon Press, 2011.

Nieborg, David B., and Anne Helmond. “The Political Economy of Facebook’s Platformization in the Mobile Ecosystem: Facebook Messenger as a Platform Instance.” Media, Culture & Society, vol. 4, no. 2, 2019, pp. 196-218.

Pantelides, Kate, et al. “Eight Years a ‘Wooden Opponent’: Genre Change (and its Lack) in Campus Timely Warnings.” Present Tense, vol. 5, no. 3,2014, www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-5/eight-years-a-wooden-opponent-genre-change-and-its-lack-in-campus-timely-warnings/. Accessed 1 August 2020.

Rickman, Aimee. Adolescence, Girlhood, and Media Migration: U.S. Teens’ Use of Social Media to Negotiate Offline Struggles. Lexington Books, 2018.

Riedner, Rachel C. Writing Neoliberal Values: Rhetorical Connectivities and Globalized Capitalism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Rushing Daniel, James. “Everybody Will Be Hip and Rich: Neoliberal Discourse in Silicon Valley.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, vol. 6, no. 2, 2017. www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/everybody-will-be-hip-and-rich/. Accessed 2 August 2020.

Shearer, Elisa and Elizabeth Grieco. “Americans Are Wary of the Role Social Media Sites Play in Delivering the News.” Pew Research Center, 2 October 2019, www.journalism.org/2019/10/02/americans-are-wary-of-the-role-social-media-sites-play-in-delivering-the-news/. Accessed 2 August 2020.

Steinberg, Laurence. “Expecting Students to Play It Safe if Colleges Reopen Is a Fantasy,” The New York Times, 15 June 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/06/15/opinion/coronavirus-college-safe.html. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Tufekci, Zeynep. Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press, 2017.

Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Waddell, Kaveh. “Facebook Approved Ads with Coronavirus Misinformation.” Consumer Reports, 7 April 2020, www.consumerreports.org/social-media/facebook-approved-ads-with-coronavirus-misinformation/. Accessed 3 August 2020.

Will, George F. “Much of Today’s Intelligentsia Cannot Think.” The Washington Post, 26 June 2020, www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/most-of-todays-intelligentsia-cannot-think/2020/06/25/987cf0c4-b714-11ea-a8da-693df3d7674a_story.html. Accessed 4 August 2020.

Wong, Julia Carrie and Hannah Ellis-Peterson. “Facebook Planned to Remove Fake Accounts in India – Until it Realized a BJP Politician was Involved.” The Guardian, 15 April 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/apr/15/facebook-india-bjp-fake-accounts. Accessed 15 April 2021.

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: The Resistance. NYC This Afternoon. Facebook.

KEYWORDS: COVID, neoliberalism, social media, rhetorical analysis, panopticon

Aimee Rickman's work considers youth and social technologies. She is an ethnographer and associate professor of Child and Family Science at California State University where she directs the Youth & Social Media Research Lab. Her writing has appeared in various scholarly and mainstream publications, and she is author of Adolescence, Girlhood, and Media Migration: US Teens' Use of Social Media to Negotiate Offline Struggles (Lexington, 2018).

Aimee Rickman's work considers youth and social technologies. She is an ethnographer and associate professor of Child and Family Science at California State University where she directs the Youth & Social Media Research Lab. Her writing has appeared in various scholarly and mainstream publications, and she is author of Adolescence, Girlhood, and Media Migration: US Teens' Use of Social Media to Negotiate Offline Struggles (Lexington, 2018).  Alexandra J. Cavallaro is an associate professor in the English Department and director of the Center for the Study of Correctional Education at California State University, San Bernardino. Her research focuses on three interconnected areas of interest: literacy studies, critical prison studies, and queer studies. Her work has appeared in enculturation: a journal of writing, rhetoric, and culture, Community Literacy Journal, and Literacy and Composition Studies.

Alexandra J. Cavallaro is an associate professor in the English Department and director of the Center for the Study of Correctional Education at California State University, San Bernardino. Her research focuses on three interconnected areas of interest: literacy studies, critical prison studies, and queer studies. Her work has appeared in enculturation: a journal of writing, rhetoric, and culture, Community Literacy Journal, and Literacy and Composition Studies.