Rubles and Rhetoric: Corporate Kairos and Social Media’s Crisis of Common Sense

At the end of 2017, Facebook—and, to a lesser extent, Twitter—came under fire for accepting $100,000 in advertising money from Russian actors during the 2016 US presidential election (Shane and Goel). This money was used to publish several political ads that were generated by a troll farm known as the Internet Research Agency. In a written testimony to the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism, Facebook executives revealed that 29 million Facebook users were served with that content directly (Isaac and Wakabayshi).

Due to Facebook’s engagement-based algorithm, approximately 126 million people may have seen the ads. Assuming that many people who may have been served the ads may not have logged in that day, may have scrolled by, or may not have interacted with them at all, Facebook estimates that only about 11.4 million people saw the ad (Byers). Around 3,000 of these ads also appeared on Instagram, owned by Facebook (Byers). It has not been reported how many users were served the Instagram ads.

In this article, we investigate the platform politics and technological dynamics at play on Facebook that allowed Russian politically motivated advertisements to be purchased with Rubles during the 2016 election season. These ads were purchased using a currency that clearly indicated an attempt by a foreign power to influence a US election, something prohibited by the FEC (Federal Election Commission, “Foreign Nationals”). In the Senate judiciary subcommittee hearing, Senator Al Franken asked Facebook VP Colin Stretch, “American political ads and Russian money: rubles. How could you not connect those two dots?”

Facebook’s inattention to rubles as payment for advertising is a high-profile example of the larger ethical issues in social media and a demonstration of the power of what we call corporate kairos (West and Pope), the need/desire of corporate actors to bypass the normal rules of audience access on social media to specifically target the individuals they want to impact exactly when they want to impact them. In this piece, we add to the conversation on corporate kairos by underscoring the ways that Facebook’s platform is not only built around pay-to-play access-on-demand, but that this lucrative system is almost entirely driven by algorithms with no meaningful checks against unethical usages.

Not unlike previous research on administrative scandals in the field such as Challenger (Dombrowski; Moore), Columbia (Dombrowski), and Ford (DeGeorge; Bryan), we focus on the cultures and attitudes that lead to such behavior as much as the behavior itself from bad actors. In addition, we join the increasing number of scholars who are looking at the ways that platforms allow such behavior through their algorithms, as well as how researchers can and should make more visible the effects of both human and non-human actors (Beck; Gillespie; Gruwell; Lee; Noble; Wachter-Boetthcher). The pervasiveness of the cultural issues at Facebook, which we only scratch the surface of in this article, can be seen in recent reports that the platform has gone so far as to auto-generate pages for hate groups (De Chant). As we examine the specific case of interference from Russian troll farms on social media during the 2016 US presidential election, we further extend these conversations by discussing how Facebook’s algorithm allowed for and even facilitated this interference.

As the 2020 US election and subsequent January 6 Insurrection showed, political ads and misinformation have become standard pieces of the content we consume and a guiding force in the public’s conception of the current political and cultural landscape (Bridgman et al.; Love and Karabinus; Skinnell). Pew Research Center reports that about two in ten US adults get the majority of their political news on social media platforms—and this number doesn’t even consider the number of adults who only get some of their political news from social media (Jurkowitz and Mitchell). Because of this, we find it necessary to look back at this controversy to understand just how fundamental and working-as-intended this activity was/is for social media and the ethical/social implications it raises for us as writers in social media and professional spaces. To do this, we will first broadly discuss the types of ads that were created by the Internet Research Agency during the 2016 US Presidential Election. We will then use our concept of corporate kairos to show how these ads were able to be posted, why these ads were ultimately successful, and what this means for users, researchers, and teachers of these platforms.

Russian Troll Farm Ads During a US Election

For the most part, the ads and promotions that were produced by the Internet Research Agency were related to what the troll farm considered to be divisive political topics: LGBTQ+ rights, gun rights, undocumented immigrants’ legal status, etc. The goal of many of these ads was to sow seeds of discord within the American political system, stoke racial and cultural tensions, and even to infiltrate political movements like the Black Lives Matter movement.

The more controversial the ad or promotion, the more comments, shares, and reactions it usually got. And due to Facebook’s engagement-based algorithm, controversial ads or promotions were more likely to be seen by an even larger audience. The correlation between activity on a post and the resultant exposure creates a perverse incentive for content that is controversial or unethical as a way to boost a given piece of content’s rhetorical velocity (Ridolfo and DeVoss) and to get even more value out of a given ad buy.

And this strategy was effective: one the most popular of the troll farm’s 470 Facebook groups was “Blacktivist,” a fake group that claimed to support community organizing for the Black Lives Matter movement (O’Sullivan and Byers). By creating and promoting controversial posts intended to spark outrage, the group gained more than 500,000 followers, more than the platform-verified Black Lives Matter official page at that time. Put another way, the rhetorical velocity of the fake group outpaced that of the actual Black Lives Matters group when measuring by the metric of followers. It is worth noting that as far as we’re aware, none of this raised any red flags for Facebook.

After the Senate subcommittee hearing, Facebook released what it called a few “representative samples” of the Russian ads and promotions (Shane and Goel). These ads use a variety of rhetorical strategies, which we could discuss at length but that isn’t our intention here. Instead, we use Figure 1 to show a few example advertisements/sponsored posts so that you can see the type of content that went unnoticed by any of Facebook’s algorithms.

In Figure 1, the first advertisement links users to a petition to have Hillary Clinton removed from the 2016 Presidential Ballot because the “dynastic succession of the Clinton family in American politics breaches the core democratic principles laid out by our Founding Fathers.” The second post shows a picture of three people in burqa with question marks over their faces. It encourages users to “like and share if you want burqa banned in America” and includes the name of the group, “Stop All Invaders.” The third post shows an illustration of Satan and Jesus arm wrestling with the following text imposed on the image: “Satan: If I win Clinton wins! Jesus: Not if I can help it! Press ‘Like’ to Help Jesus Win!”

Corporate Kairos’s Function in Ad Creation and Distribution

Throughout the subcommittee hearing and in related media coverage, Facebook—and Twitter—executives have made it clear that this Russian-influenced content was only a small percentage of content that was generated during that time period. While this may be true, the question we are considering is not to what extent this social media influence impacted the election results. Instead, we ask, how was a Russian troll farm able to purchase ad space for their content? For us the answer is fairly simple: the system was working as intended, giving blind access to all users based on user data that is accessible to anyone who can pay for it.

We define corporate kairos in our 2018 Present Tense article as “the demand of corporate members of social media platforms to circumvent the normal rules of rhetorical velocity and kairos” (West and Pope). To create our definition, we draw on David Sheridan, Jim Ridolfo, and Anthony Michel’s definition of the kairotic struggle as “the way a rhetor composes a text to ensure its success in a particular situation,” and they note, “the rhetorical process exceeds the composing process; the rhetor’s work is not done when the composition is done” (60). We also draw on the idea of rhetorical velocity from Ridolfo and Devoss’s 2009 Kairos article, defined as “a strategic approach to composing for rhetorical delivery. It is both a way of considering delivery as a rhetorical mode, aligned with an understanding of how texts work as a component of a strategy.”

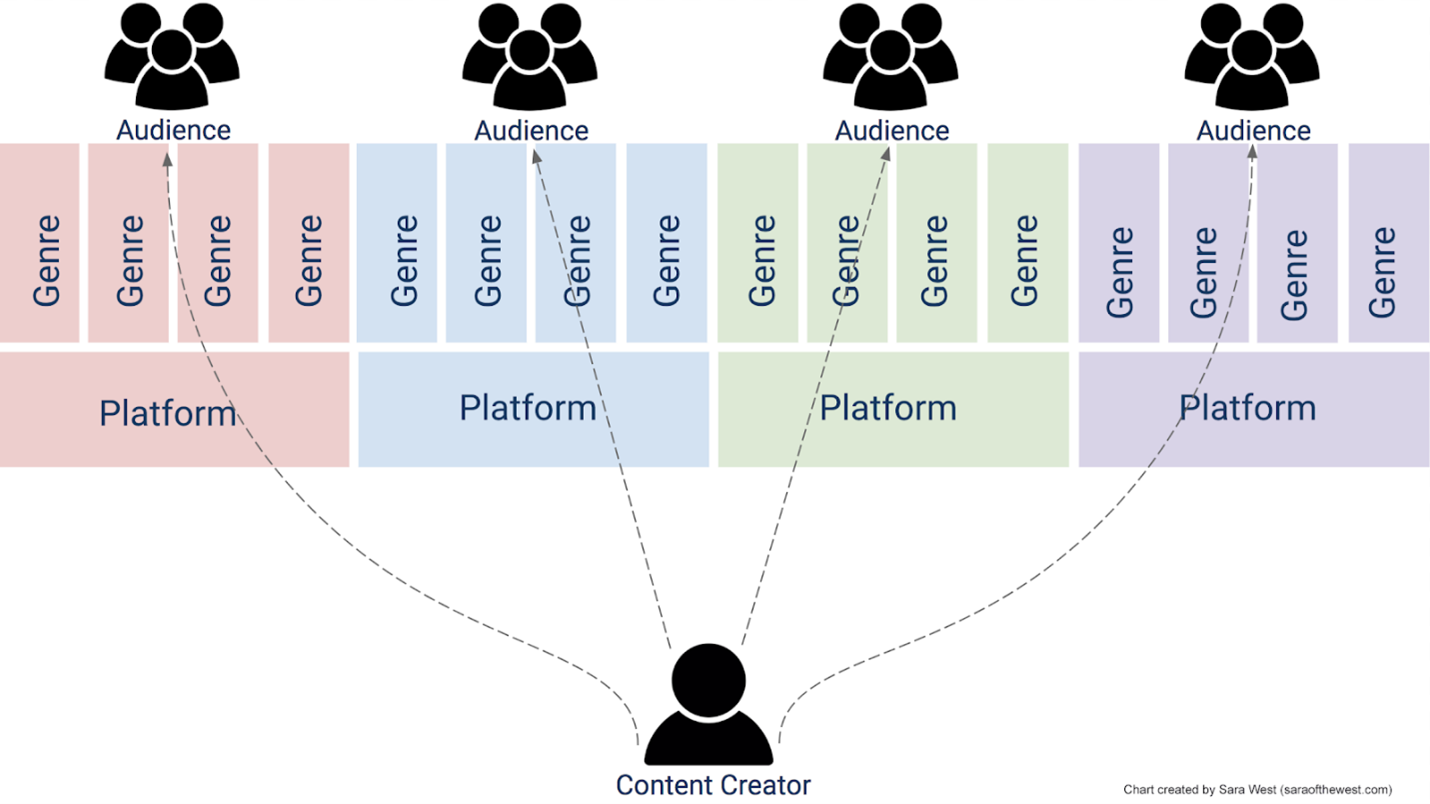

For us, corporate kairos is best understood when set in opposition to what is available to normal, non-corporate (or non-paying) users of social media. The average user or content creator has to first understand the demands of the platform, as well as the types of content the platform allows and/or privileges. For example, Facebook privileges content that leads to engagement (reactions, shares, comments). Then the content creator will craft their message using a certain genre which is likely already in action for the platform, like a meme or a certain visual or textual convention, as illustrated in Figure 2. For the average user, going viral intentionally is hard work and often out of reach.

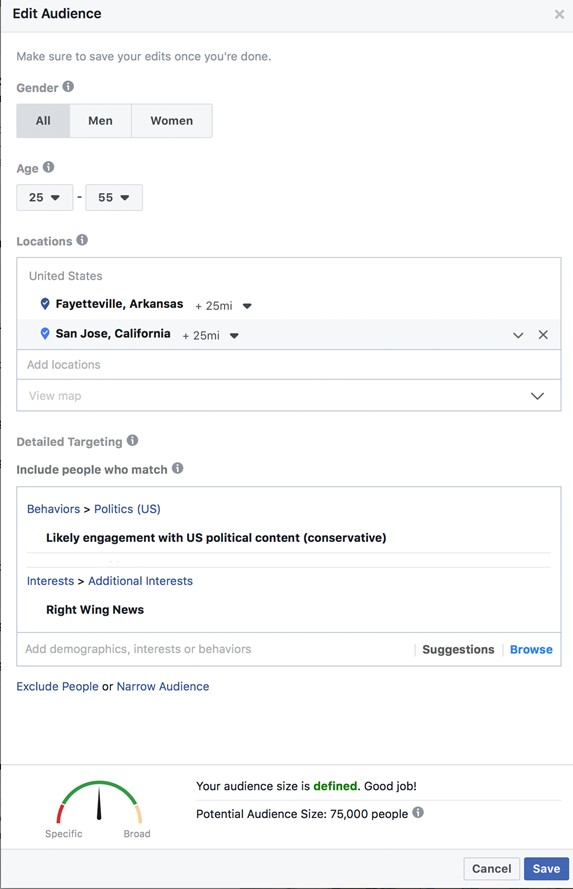

Corporate kairos is the fundamental opposite of the average user’s content creation process, as most social media platforms provide tools to corporate (or paying) users so that they can deliver content directly to their chosen audience. Figure 3 below shows the relative ease that paying users have in targeting a specific audience on Facebook. In this example, we target an ad to users 25-55, located within 25 miles of either San Jose, CA, or Fayetteville, AR, who are identified (by Facebook’s algorithm) as conservative and who also show an interest in Right Wing news. Were we to post an ad to this audience, we’d be able to reach 75,000 users without worrying about choosing the right genre or content to our audience.

It does help, however, when that content is rhetorically and contextually savvy. When the Internet Research Agency created ads for the Facebook platform, they showed a considerable amount of rhetorical dexterity in that these ads looked like something you’d find already on Facebook. In addition, they relied on already controversial topics like the Clinton family history and immigration, as well as traditional assumptions about the political parties by using appeals to Christian imagery, for example, to villainize Hillary Clinton (Figure 1). They also gave Facebook the engagement that it wanted since these ads often ignited arguments that resulted in more comments and reactions by the audience.

The difference between the Internet Research Agency and the average user, however, is that the group was able to specifically craft their kairotic moment by using Facebook’s platform tools. They could trick Facebook’s users by producing content that looked like it fit on the site; they could make use of Facebook’s algorithms simply by having the money to bypass the system normal users have to make use of. The corporate kairos of ad buys combined with controversial content overpowered what many consider to be a kairotic and vital social movement (Hidalgo and Sackey).

In this way, by granting corporate users the ability to craft messages using a paywalled corporate kairos, social media platforms exert control on rhetorical velocity. Just think about the Internet Research Agency’s 29 million ad-served users compared to the 129 million who may have actually been shown the ad. All of this, as far as social media goes, is simply working as intended. Views are money, and those views are available to the people and organizations who are willing to pay for them.

Conclusion: A Call for Critical Engagement

Platforms like Facebook create advertising algorithms that are capable of targeting an audience on the most minute detail, but—to get at our larger concern here—they simply choose not to use that same power to screen ads that violate federal and state laws. And this isn’t a one-time occurrence, as investigative journalism has shown us over and over again (Angwin, Varner, and Tobin, “Facebook (Still) Letting Housing Advertisers”). After all, Facebook makes money from the purchase of the ad; it doesn’t make money based on who purchased the ad. The corporate kairos users’ data is simply not valuable to them when held up against data mined from the masses of users that connect and communicate on their platforms.

As with much of Silicon Valley, a lot of the work done at Facebook is automated, especially when dealing with paid content and content that garners high engagement (Amadeo). That is how, later in 2017, Facebook both assigned users anti-Semitic designations and allowed paying users to target ads to users with this designation (Angwin, Varner, and Tobin, “Facebook Enabled Advertisers”). And, more recently, it’s how 40% of news about the COVID-19 Pandemic that had already been debunked by fact-checkers still remained on the site (Scott). These occurrences, for us, get at the larger ethical dilemma surrounding corporate kairos: all of this happens with no one at the wheel.

The lack of engagement with the algorithms that support corporate kairos is a continuation of what social media has done so well: taken system-centered design and repackaged it into something “new” (Johnson). The average user on these platforms simply has to adapt to the way the system works, the genres that are available, and the types of posting available. These systems are user-centered in that they care about who the users are and what they do or like, but the true users of this system are the ones the system has been oriented around serving for a profit: the corporate kairos users who buy their way into the placement and audience they want.

For us, the example of the Internet Research Agency’s infiltration into social media platforms like Facebook—as well as the creation and success of groups like Blacktivist and others—speaks to the larger issue that we face as technical writers and communicators. We often treat social media platforms as unbiased and even playing fields. How many of us have asked students to “go viral” for an assignment, or pulled up an amusing web video that has spread online and wondered at the novelty of it all? But these are not innocent platforms, and these algorithms are not there for “us,” the average user. They are in service to the corporate kairos user, the one who pays for everything that we see and fuels the constant onslaught of paid content.

We need to push ourselves and our students to not treat these platforms as innocent, and to understand and ethically approach the vast store of user data available for corporate or paying actors on these platforms. These spaces need critical users to help advocate for more transparent practices by advertisers and platforms, and we need to begin to think critically about how this mode of publication basically bypasses traditional notions of kairos and alters the ways we talk about audience and rhetorical velocity.

As teachers of writing and communication and online texts in particular, we need to impress on our students how to critically engage with texts that are primarily placed in front of them via corporate kairos, and how to trace the origin and motive of these texts on platforms that often go to great lengths to hide this vital information.

Works Cited

Amadeo, Ron. “Terraria Developer Cancels Google Stadia Port after YouTube Account Ban: Hit Indie Game Developer Tells Google, ‘Doing Business with You Is a Liability.’” Ars Technica, 8 Feb. 2021, arstechnica.com/gadgets/2021/02/terraria-developer-cancels-google-stadia-port-after-youtube-account-ban/. Accessed 12 Apr. 2021.

Angwin, Julia, Madeleine Varner, and Ariana Torbin. “Facebook Enabled Advertisers to Reach ‘Jew Haters.’” ProPublica, 14 Sept. 2017, www.propublica.org/article/facebook-enabled-advertisers-to-reach-jew-haters. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

—. “Facebook (Still) Letting Housing Advertisers Exclude Users by Race.” ProPublica, 11 Nov. 2017, www.propublica.org/article/facebook-enabled-advertisers-to-reach-jew-haters. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

Beck, Estee. “A Theory of Persuasive Computer Algorithms for Rhetorical Code Studies.” Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, vol. 23, 2016, enculturation.net/a-theory-of-persuasive-computer-algorithms. Accessed 11 Mar. 2020.

Bridgman, Aengus, et al. “Infodemic Pathways: Evaluating the Role That Traditional and Social Media Play in Cross-National Information Transfer.” Frontiers in Political Science, vol. 3, Frontiers, 2021. Frontiers, doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.648646.

Bryan, John. “Down the Slippery Slope: Ethics and the Technical Writer as Marketer.” Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 1, 2009, pp. 73–88.

Byers, Dylan. “Facebook Estimates 126 Million People were Served Content from Russian-linked Pages.” CNN Business, 31 Oct. 2017, money.cnn.com/2017/10/30/media/russia-facebook-126-million-users/index.html. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

De Chant, Tim. “Facebook Has Been Autogenerating Pages for White Supremacists: Facebook’s Efforts to Combat Extremism Remain at Odds with Engagement Goals.” Ars Technica, 25 Mar. 2021, arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2021/03/facebook-is-autogenerating-pages-for-white-supremacists/. Accessed 12 Apr. 2021.

De George, Richard T. “Ethical Responsibilities of Engineers in Large Organizations: The Pinto Case.” Business & Professional Ethics Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, 1981, pp. 1–14. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27799725. Accessed 19 Apr. 2020.

Dombrowski, P.M. “The Evolving Face of Ethics in Technical and Professional Communication: Challenger to Columbia.” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, vol. 50, no. 4, 2007, pp. 306–19.

Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Politics of ‘Platforms.’” New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, 2010, pp. 347–364, doi:10.1177/1461444809342738.

Gruwell, Leigh. “Constructing Research, Constructing the Platform: Algorithms and the Rhetoricity of Social Media Research.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, 23 Jan. 2018, www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/corporate-kairos-and-the-impossibility-of-the-anonymous-ephemeral-messaging-dream/. Accessed 11 Mar. 2020.

Federal Election Commission. “Foreign Nationals.” Federal Election Commission: United States of America, www.fec.gov/updates/foreign-nationals/. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Hidalgo, Alexandra, and Donnie Johnson Sackey. “Special Issue on Race, Rhetoric, and the State: Introduction.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, vol. 5, no. 2, www.presenttensejournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/SpecialIssueIntroduction_Transcript.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

Isaac, Mike, and Daisuke Wakabayashi. “Fake Russian Facebook Accounts Bought $100,000 in Political Ads.” The New York Times, 30 Oct. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/10/30/technology/facebook-google-russia.html. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

Johnson, Robert R. User-Centered Technology: A Rhetorical Theory for Computers and Other Mundane Artifacts. SUNY P, 1998.

Jurkowitz, Mark, and Amy Mitchell. “Americans Who Primarily Get News through Social Media are Least Likely to Follow COVID-19 Coverage, Most Likely to Report Seeing Made-up News.” Pew Research Center, 25 Mar. 2020, www.journalism.org/2020/03/25/americans-who-primarily-get-news-through-social-media-are-least-likely-to-follow-covid-19-coverage-most-likely-to-report-seeing-made-up-news/. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

Lee, Nicol Turner. “Detecting Racial Bias in Algorithms and Machine Learning.” Journal of Information, Communication, & Ethics in Society, vol. 16, no. 3, 2018, pp. 252–60.

Love, Patrick, and Alisha Karabinus. “Creation of an Alt-Left Boogeyman: Information Circulation and the Emergence of ‘Antifa.’” Platforms, Protests, and the Challenge of Networked Democracy, edited by John Johns and Michael Trice, Palgrave Mcmillen, 2020, pp. 173–198.

Moore, Patrick. “When Politeness is Fatal: Technical Communication and the Challenger Accident.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 6, no. 3, 1992, pp. 269–92.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. NYU P, 2018.

O’Sullivan, Donie, and Dylan Byers. “Exclusive: Fake Black Activist Accounts linked to Russian Government.” CNN Business, 28 Sept. 2017, money.cnn.com/2017/09/28/media/blacktivist-russia-facebook-twitter/index.html. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

Ridolfo, Jim, and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss. “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery.” Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol. 13, no. 2, 2009, kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/intro.html. Accessed 11 Mar. 2020.

Scott, Mark. “Facebook to Tell Millions of Users They’ve Seen ‘Fake News’ about COVID-19.” Politico, www.politico.eu/article/facebook-avaaz-covid19-coronavirus-misinformation-fake-news/. Accessed 20 Apr. 2020.

Shane, Scott, and Vindu Goel. “Fake Russian Facebook Accounts Bought $100,000 in Political Ads.” The New York Times, 6 Sept. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/09/06/technology/facebook-russian-political-ads.html. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

Sheridan, David M., Jim Ridolfo, and Anthony J. Michel. The Available Means of Persuasion: Mapping a Theory and Pedagogy of Multimodal Public Rhetoric. Parlor Press, 2012.

Skinnell, Ryan. “What Passes for Truth in the Trump Era: Telling it Like It Isn’t.” Faking the News: What Rhetoric Can Teach Us about Donald J. Trump, edited by Ryan Skinnell, Imprint Academic, 2018, 76–94.

Wachter-Boettcher, Sara. Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and the Other Threats of Toxic Tech. W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

West, Sara, and Adam R. Pope. “Corporate Kairos and the Impossibility of the Anonymous, Ephemeral Messaging Dream.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, 20 Jan. 2018, www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/corporate-kairos-and-the-impossibility-of-the-anonymous-ephemeral-messaging-dream/. Accessed 11 Mar. 2020.

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: Created by author, Adam Pope.

KEYWORDS: social networking, kairos, election, rhetoric, internet

Sara West is an assistant professor in the Professional and Technical Writing Program at San José State University. She teaches courses in professional writing, editing and document design, and content writing and strategy. Her research interests include social media studies, anonymity and ephemerality in online spaces, and technical and professional writing pedagogies. She also has a lot of (positive) feelings about cats.

Sara West is an assistant professor in the Professional and Technical Writing Program at San José State University. She teaches courses in professional writing, editing and document design, and content writing and strategy. Her research interests include social media studies, anonymity and ephemerality in online spaces, and technical and professional writing pedagogies. She also has a lot of (positive) feelings about cats.  Adam R. Pope is an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas. He is the founder and director of the Graduate Certificate in Technical Writing and Public Rhetorics and currently interim director of the Rhetoric and Composition program. His research interests include online technical writing, natural language processing and rhetoric, and institutional research. He resides in Northwest Arkansas with his wife, three children, two dogs, two cats, and five chickens.

Adam R. Pope is an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas. He is the founder and director of the Graduate Certificate in Technical Writing and Public Rhetorics and currently interim director of the Rhetoric and Composition program. His research interests include online technical writing, natural language processing and rhetoric, and institutional research. He resides in Northwest Arkansas with his wife, three children, two dogs, two cats, and five chickens.