Fear and Loathing—of Disability on the Campaign Trail

“Person. Woman. Man. Camera. TV.”

—President Donald Trump

Throughout the 2020 election cycle, rhetorical contortions of disability have been a constant refrain: stories of candidates “overcoming” their disabilities; new waves of President Trump’s nicknames rooted in disability for political opponents, media figures, and anyone who draws his ire; and pundits making assumptions about candidates mental and physical fitness seem inevitable in each news cycle.

In July of 2020, leading up to the presidential election, President Trump repeated the list “Person. Woman. Man. Camera. TV,” describing it as “amazing” that he could recall these words. The test was the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, designed in-part to detect signs of cognitive decline associated with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or other mental disabilities. Trump’s argument, in short, was that he was fit for office simply because he did not have a diagnosable disability. For Trump, it is ultimately the presence of disability that is delegitimizing, not actual job performance. Iterations of this argument appeared in how Trump responded to others, often branding them as unfit because they were disabled (though in many cases they were not).

But it wasn’t just Trump: commentators on both sides of the aisle made assumptions about the fitness of candidates based on disabilities or presumed disabilities. Simply because of their supposed disabled status, certain candidates are constructed as unfit to hold elected office unless, I argue, they can perform ablenormativitiy and “overcome” or disguise their disability.

This ableist rhetoric impacts disabled people beyond the immediate contexts of the candidates being deligitimized through accusations of disability. When disability—alleged or otherwise—is weaponized to deny the legitimacy of a candidate, it has ripple effects that impact the real lives of disabled people. These ableist framings pressure certain disabled people to mask their disabilities. At the same time, the ablenationalist project strips many disabled people of agency as democratic subjects. Consider, for example, the tens of thousands of disabled Americans who are denied the right to vote on the basis of their disability.

My argument is that the ableist rhetorical framing of disability in the 2020 campaign trail has predominantly been used to delegitimize candidates for alleged disabilities—and in doing so, has contributed to an ableist project further stigmatizing disabled people and situating them as outside of the possibility of democratic agency. Furthermore, I argue that this ablenationalist project by which disabled bodyminds are delegitimized is more difficult to critique in a political culture of demagoguery that ultimately dismisses critiques of ableism as partisan critiques against a political party, as well as uses authoritarian dismissal of disabled people as rhetorically suspect.

Ablenationalism, Delegitimization, and Disability

In order to understand the rhetorical deployment of disability as delegitimizing on the 2020 campaign trail, I turn to ablenationalism.1 Coined by disability theorists Sharon Snyder and David Mitchell, ablenationalism refers to “the degree to which treating people with disabilities as an exception valorizes able-bodied norms of inclusion as the naturalized qualification of citizenship” (113). Ablenationalism consists of several interlocking functions including austerity cuts to key services, insistence that America treats disabled people better than other nations (while ignoring how disabled Americans are actually treated), and other national projects that shape policies and responses to disabled people (Mitchell and Snyder, Biopolitics, 35). Here I focus particularly on the ablenationalist process on which some are deemed “outside” of the nation’s best interests (Mitchell and Snyder 17). In other words, ablenationalism is willing to accommodate disabled people to a point, and past that point the exclusion of others seems justified or even inevitable. This process delegitimizes certain disabled people and casts their rhetoricity as suspect.

Consider how disability is frequently deployed specifically to delegitimize disabled bodyminds and their participation in political processes. I realize when I bring up both disability and Trump, many people are quick to point to the moment from the 2016 presidential election when Trump mocked “that disabled reporter.” I must interject that “that disabled reporter” is Serge Kovaleski, who has won both a Pulitzer Prize and a George Polk Award for his work as a journalist. I don’t mention these awards to claim Kovaleski is too accomplished to mock—disabled people should not need accolades to avoid ableist mockery by presidential nominees—but to point out that this delegitimization based on disability is a frighteningly effective rhetorical strategy. The mocking is easily recalled, but less so is Kovaleski’s actual refutation of Trump’s claims about Muslim Americans. As rhetoric scholar Jennifer Mercieca writes, “Trump’s impersonation was itself an argument: his parallel case argument compared Kovaleski’s imparied body to what Trump believes was his impaired recollection of the 9/11 celebrations” (54). Mercieca points to how Trump was able to foment distrust of Kovaleski and his argument, that—after the ableism of Trump’s mockery was pointed out—Trump doubled down, claiming Kovaleski was only seeking attention “further impugning Kovaleski’s credibility” (56). The point is not simply that Trump mocked Kovaleski’s disability. It was that this mocking was deployed specifically to deny Kovaleski’s critiques. Trump’s ableist rhetoric deligitimized Kovaleski based on his disability, ultimately delegitimizing the critique itself.

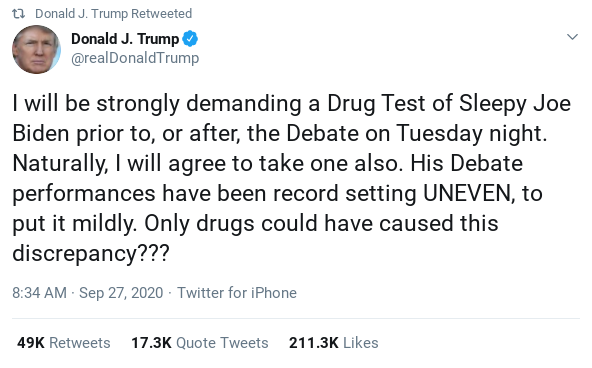

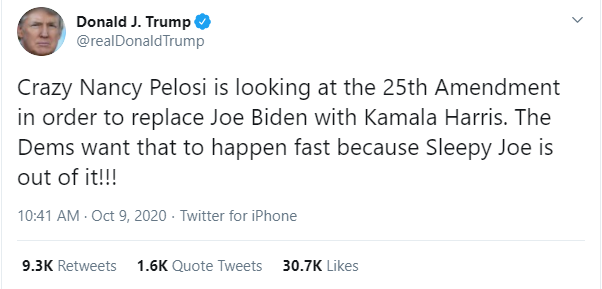

With this example of Serge Kovaleski, we see Trump leverage ablenationalism to sidestep critique. Ablenationalism functions to “represent the nation as synonymous with a narrow array of acceptable body types” (Snyder and Mitchell, 115).2 This deployment of disability to delegitimize dissenting voices and sidestep critiques is one of Trump’s rhetorical mainstays: His recurring misogynistic and ableist characterizations of women as “crazy,” “wacky,” “mad,” or “deranged”—including Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi, Kamala Harris, or his former aide Omarosa Manigault Newman—and that’s an incredibly truncated list. He referred to Democratic Congresswoman Maxine Waters as “Low IQ Maxine,” which invokes the eugenic, racist history of IQ testing with a wink and a nod—highlighting how ablenationalism intersects with race. Ablenationalist delegitimizing has become a staple of his 2020 campaign, as he repeatedly caricaturizes Democratic Presidential Candidate Joe Biden as being mentally unfit, frequently calling him “slow Joe,” or “Sleepy Joe.” These attacks were repeated in the first presidential debate, where Trump disparaged Biden’s perceived intelligence. In these cases, Trump deploys ableist rhetoric to delegitimize his opponent. They are illegitimate not because of any particular policy decision or because of their actual performance as an elected official but because they are presumed to be disabled.

Writing about Trump’s ableism leading up to the 2016 election, Andrew Harnish writes that this ableist rhetoric works well as a rhetorical strategy because Trump’s base “are deeply fearful of disability” (424). This fear of disability folds well into Trump’s demagogic rhetoric described by Jennifer Mercieca in her extended analysis of President Donald Trump’s demagogic rhetorical strategies, where Mercieca notes that one of the criteria of dangerous demagogues is that they “use weaponized rhetoric to deny the legitimacy of political opponents as nonhuman enemy objects who are illegitimate” (206). Trump uses disability as a smokescreen: he can avoid critiques about his policies and statements if he can frame those who raise these concerns as disabled—and by ablenationalist extension, their critiques as illegitimate. As we see with Trump’s repeated attacks on Biden’s mental health, his alleged mental deficits are rhetorically constructed as delegitimizing.

And it’s important to note this rhetorical strategy of framing political opponents isn’t just a Trumpian talking point: Early in September 2020, ABC News first reported on a Department of Homeland Security document titled “Russia Likely to Denigrate Health of US Candidates to Influence 2020 Election” in a report that detailed Russian disinformation campaigns were likely to spread rumors about declining mental health targeting Biden. According to ABC News, the Trump administration chose to withhold the document, a move inline with Trump’s attempts to denigrate Biden’s mental fitness.

And, though the Presidential podium has afforded Trump a highly visible platform for his rhetorical delegitimizing of disabled bodyminds, it’s important to note that pundits on the left seem caught up in this same rhetorical process. MSNBC host John Heilemann, as one example, has claimed Trump shows signs of “advanced dementia.” In reference to Trump’s 2019 visit to Walter Reed hospital, CNN political analysis Joe Lockhart tweeted a question asking if Trump was hiding a stroke from the public—a claim Trump has refuted. Trump’s bodily autonomy has frequently been brought into question, from Trump using both hands to drink from a glass to #rampgate—where Trump appeared to experience difficulty descending a ramp after a commencement speech at Westpoint. In each of these cases, commentators questioned Trump’s legitimacy because of supposed disability. As Rebecca Cokley has argued, “the ableism that pervades society makes it easy to argue that someone is a failure because they’re disabled,” rather than framing these arguments in ethics, qualifications, or actual record. Telling of the ableist implications, #rampgate trended alongside #TrumpIsNotWell. Ablenationalist rhetoric is clearly a bipartisan project.

I also touch briefly on another function of ablenationalism: the process by which certain disabled people are considered “abled-enough” and typically must demonstrate they’ve somehow “overcome” their disability and are then “fashioned as a population that can be put into service on behalf of the nation-state rather than exclusively positioned as parasitic” (Mitchell and Snyder, 17). Consider both Biden’s stutter and congressional candidate Madison Cawthorn’s paralysis. In interviews, Biden has shared his strategies for overcoming his stutter, which he claims is “the only handicap that people still laugh about.” Cawthorn concluded his speech at the Republican National Convention by declaring “Be a radical for our republic, for which I stand, one nation under God, with liberty and justice for all,” as he stood up from his wheelchair. The focus on overcoming disability in these moments isn’t celebrating disability, rather they further delegitimize disabled folks by telling them that abled counterparts are the ideal democratic subject. While I am not trying to undermine the efforts of disabled people who devote considerable energy to practicing speaking without stutters or other projects, I point to the culture of ableism that pressures disabled people to meet ableist norms. The embedded ablenationalist message in these overcoming narratives is that disabled bodyminds must overcome their stutter, mobility devices, or other apparently disqualifying defects before they are fit for office.

Demagoguery and Disability

As I’ve already discussed, Trump isn’t the only person deploying disability in a way that delegitimizes disabled people and contributes to the project of ablenationalism. But because of his platform and charismatic leadership style, Trump’s deployments are arguably the loudest. Patricia Roberts-Miller describes Trump’s “charismatic leadership” that silences dissent, precludes criticism, and is grounded in subverting critical thinking to pure identification” (“Charisma,” 96). Trump’s ableist remarks and repeated deployment of disability as delegitimizing is unlikely to bother his followers because they identify with Trump (or at least the party), and, therefore, “many Trump voters harbor at least a tacit belief that the man behind the curtain is more decent and upstanding than his morally abhorrent stumping would seem to suggest” (Gunn 162). This implicit trust in Trump makes getting his followers to engage with conversations about the ablenationalist project of deligitimizing disabled people difficult. There is a refusal to address the language and assumptions—to say nothing of the policies—that impact disabled people, a phenomena that echoes Roberts-Miller’s extensive rhetorical study of the culture of demagoguery.

As Roberts-Miller’s scholarship on demagoguery suggests, demagoguery isn’t simply about the person of the demagogue but the culture of demagoguery. Roberts-Miller writes “demagoguery is about identity. It says that complicated policy issues can be reduced to a binary of us (good) and them (bad)” (8). Demagoguery reduces issues to ingroup and outgroup, making it quite difficult to critically engage with the idea that these deployments of disability are ableist—on either side of the aisle. But demagogues frequently utilize authoritarian logics to direct aggression toward bodyminds deemed to be socially deviant or abnormal (Roberts-Miller, Rhetoric, 23). Candidates using disability to delegitimize their opponents are tapping into an American loathing of disabled people, which reinforces the ableist framework to begin with.

I argue that disabled people find ourselves doubly shut out by demagoguery under ablenationalism. Firstly, any criticism of these ablenationalist rhetorics would have to navigate a hyper-partisan Democrat/Republican divide. In short, to respond to ableist language of either party is to often be dismissed as part of the outgroup. A democratic commentator might mock Trump’s difficulty with a ramp, for example, and should disabled people push back against this ableism of such mocking, they may be dismissed as simply being pro-Trump, rather than anti-ableist. This presents a refusal to engage in the actual language that delegitimizes disabled people, which leads directly to the double-bind: because of the persistence and cultural acceptability of ableist exclusion of certain disabled minds, the very rhetorical agency of disabled folks trying to make these critiques is already in question.

Of course, I don’t mean to denigrate the efforts of disabled organizers who are promoting policies for disabled people—trading in ablenationalism for apathy, delegitimizing my fellow disabled people in another way. I point to efforts like #CripTheVote, a nonpartisan disability project created by and developed for disabled people. #CripTheVote continues to promote disabled political advocacy, from in-depth discussions of how candidates’ policies would impact disabled folks, from addressing barriers to participation, to supporting disabled candidates. Despite these ableist attacks and constant delegitimization of disabled people, many still do exercise political agency.

But this double-bind of demagoguery faced by disabled folks has stark material consequences. Consider the ways disabled people are denied democratic participation, from being barred the right to vote under incompetence laws, to state laws prohibiting felons from voting—which disproportionately impacts disabled people. Consider the rhetoric around disability in COVID-19 conversations, in which government officials have often framed disabled lives as inconsequential, culminating with President Trump retweeting a claim from a QAnon conspiracy theorist that dismissed preexisting conditions and “comorbidities” to misread a crucial CDC report on the impact of the virus.

Because of this double-bind, ablenationalism thrives under demagoguery, where the rhetorical agency—and the very lives of disabled people—are frequently dismissed. But disability should not be framed as inherently disqualifying for democratic participation, including running for office, as disability itself is not a marker that a person is unfit to serve in that capacity. Fitness must be judged on a case-by-case basis, on arguments of policy rather than perceived disability. Disability justice activist Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha argues that “Disability justice means people with disabilities taking leadership positions,” and they should not be asked to first “overcome” their disability to do so. While disability can impair a person to the degree they are no longer able to serve, the frame of disability as inherently delegitimizing is harmful to disabled people. For our political candidates, a focus on disability should not be the definitive maker of “fitness” for office. As Mercieca argues, “whether or not a political candidate or leader’s rhetoric promotes and protects democracy is the most fundamental quality in assessing their fitness for office” (204), and one aspect of this democratic project is respecting the agency of disabled people rather than delegitimizing them.

Conclusion

Ablenationalism preys upon fear and loathing of disabled people across political affiliations, as it was frequently deployed on the 2020 campaign trail by framing disabled people as illegitimate while suggesting disability automatically makes a person unfit for office, rather than consideration of that individual’s actual performance. Under a culture of demagoguery, disabled people find themselves in a double-bind, where challenging ableism is dismissed both by a hyper-partisian refusal to address actual language use as well as the undermining of disabled rhetorical agency and outright dismissing critiques of ableism.

Endnotes

- Rhetoric scholars continue to trace how disability is weaponized to deny citizenship and human rights, as Jay Dolmage establishes about the eugenic construction of disability at Ellis Island in the 20th century and Christina Cedillo establishes about racist, ableist immigration policing in the present. return

- Like Puar’s argument about Homonationalism, Mitchell and Snyder point to the normativizing force of Ablenationalism, by which disabled people may feel pressured to overachieve and to take on state-sponsored roles of “crip normativities” (118) wherein ablenationalism includes certain disabled people to suit the needs of the state while pushing others out of those deemed unworthy. return

Works Cited

Cedillo, Christina. “Disabled and Undocumented: In/Visibility at the Borders of Presence, Disclosure, and Nation.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 3, 2020, pp. 203-211.

Dolmage, Jay. Disabled Upon Arrival: Eugenics, Immigration, and the Construction of Race and Disability. The Ohio State UP, 2018.

Gunn, Joshua. “Donald Trump’s Perverse Political Rhetoric.” In Faking The News: What Rhetoric Can Teach Us about Donald J. Trump. Ed. by Ryan Skinnell. Societas, 2018.

Harnish, Andrew. “Ableism and the Trump Phenomenon.” Disability and Society, vol. 32, no. 3, 2017, pp. 423-428.

Mercieca, Jennifer. Demagogue for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump. Texas A&M UP, 2020.

Mitchell, David and Sharon Snyder. The Politics of Disability: Neoliberalism, Ablenationalism, and Peripheral Embodiment. U of Michigan P, 2015.

Puar, Jasbir. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times, 2nd ed., Duke UP, 2017.

Roberts-Miller, Patricia. “Charisma Isn’t Leadership, and Other Lessons We Can Learn from Trump the Businessman.” In Faking The News: What Rhetoric Can Teach Us about Donald J. Trump, edited by Ryan Skinnell. Societas, 2018.

—. Demagoguery and Democracy. The Experiment Press, 2017.

—. Rhetoric and Demagoguery. Southern Illinois UP, 2019.

Snyder, Sharon and David Mitchell. “Ablenationalism and the Geo-Politics of Disability.” Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2010, pp. 113-125.

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: “Any Functioning Adult for President 2020” by Thomas Cizauskas is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

KEYWORDS: disability, anti-ableism, political rhetoric, ablenationalism, demagoguery

Adam Hubrig (they/them; Twitter @AdamHubrig) is a disabled/chronically ill/autistic caretaker of cats. Their research at the intersections of composition and rhetoric, disability, and queer theory appears in CCCs, Community Literacy Journal, Reflections, and The Journal of Multimodal Rhetoric. They work as an assistant professor of English at Sam Houston State University.

Adam Hubrig (they/them; Twitter @AdamHubrig) is a disabled/chronically ill/autistic caretaker of cats. Their research at the intersections of composition and rhetoric, disability, and queer theory appears in CCCs, Community Literacy Journal, Reflections, and The Journal of Multimodal Rhetoric. They work as an assistant professor of English at Sam Houston State University.