Won’t You Be My Neighbor? Rhetorics of Investment Citizenship in Neighborly

A visit to the civic crowdfunding website Neighborly asks you to consider “which kind of neighbor are you?” Set against an illustrated backdrop of tiny houses with even tinier mailboxes and picturesque lollipop trees, the question frames the level of your investment as the level of your commitment to your community. Your financial contribution is as much about being a good neighbor as it is about being good with your money. With your investment, Neighborly invites you to join them in “building the future together.” Civic crowdfunding websites like Neighborly are modeled after traditional crowdfunding websites like Kickstarter and GoFundMe. Contributions made through civic crowdfunding websites, however, subsidize public initiatives rather than individual products or people.1 Civic crowdfunding sites have capitalized on the success of traditional crowdfunding sites to bring attention to underfunded public works projects (Brabham, Farnetl, Galuska and Brzozowska, Hills, Hunter, Scott). Like traditional crowdfunding, which mobilizes affect to generate donations, civic crowdfunding relies on affective appeals to generate revenue. These appeals to the public good construct not only a particular public but also a corresponding identity for those who believe in it and belong to it (Pope). “Which kind of neighbor are you?” Your investment is your answer.

Neighborly brokers the sale of and educates citizens on municipal bonds: how they work, how they differ from other investments, and how they can fit into an investment portfolio. It has received funding from prominent venture capital firms (Rao) and garnered significant attention from technology and financial news publications (Cortese, Rao, Field, Cutler). As a case study in civic crowdfunding, Neighborly is particularly interesting. While the language of investment appears on many civic crowdfunding websites, Neighborly makes the investment literal rather than metaphorical by brokering the sale of municipal bonds: loans obtained by state and local governments to finance public works projects. These highly specialized investment products are usually reserved for banks and investment firms due to their technical nature and high requirements for initial investment (Cortese). Municipal bond ownership among individual investors is at an all-time low (Olson and Wessel). Neighborly hopes to remediate this exigence by making municipal bonds available to investors who would otherwise be excluded from the market. Neighborly’s populist undercurrent emphasizes “increased transparency” in the investment process to “democratize access” for all. This affective appeal to democratic discourses recuperates high finance and rhetorically fuses the public good with the private market. In addition to being potentially lucrative investments, municipal bonds feel like civic engagement.

This essay explores the rhetorical implications of civic crowdfunding websites like Neighborly. Neighborly, in particular, rhetorically constructs a mode of citizenship understood and performed through financial and affective investments in one’s community. The site interpellates its audience as investment citizens through its claim to democratize investment in local governments. Investment citizenship privatizes citizenship by commodifying the public good as an investment product. It reinterprets government initiatives as opportunities for profit and constructs investment as civic engagement. This essay traces the evolution of citizenship from consumer citizenship to investment citizenship by analyzing Neighborly within the larger context of civic crowdfunding and crowdfunding initiatives.

Investment Citizenship

Investment citizenship is a natural extension of discourses that align citizenship with consumerism. Lizabeth Cohen argues that the transition from a production-based economy to a consumption-based economy during the 20th century re-situated private purchases and other consumptive practices within larger frameworks of nationalism and public identity (7-9, 345-397). Purchasing war bonds, boycotting companies, and buying American became mechanisms for enacting social change and expressing a national identity. As a result, citizenship is tied not only to the nation but also to the national economy. Saskia Sassen claims that citizenship is an economic practice as much as it is a political practice. The two are fused in what she calls economic citizenship (33-36). Consumption is “a mode of public engagement” (Asen 194) because it gives consumer-citizens a connection to the society in which they belong. The money they spend actualizes their membership in communities, organizations, and the nation. Just as there is an expectation that good citizens perform their civic duty by voting, there is an expectation that good consumer-citizens perform their civic duty by spending. Citizenship is articulated in terms of consumption and normalized as a feature of civic life.

In the 21st century, finance capital intensifies the importance of the economy for both individual and national identities (Nealon). Investment in various financial products supplements and abstracts the consumption of goods and services, ultimately rearticulating identity within neoliberal logics of profit and loss. Neoliberalism treats the free market as a template for all areas of human and, by extension, civic life. Within this framework, homo politicus is transformed into homo œconomicus—the person of politics becomes the person of enterprise (Brown 109-10). According to Foucault, homo œconomicus lives his/her life through the system of economic exchange and acts as “an entrepreneur of him[/her]self” (226). The human subject exists primarily as an economic being. Wendy Brown extends Foucault’s argument suggesting that “the rise of finance capital” (70) has produced “another version of homo œconomicus, one built on an investment portfolio model” (66). The neoliberal citizen is a “self-enterprising citizen-subject” obligated to cultivate his or her financial security through a multiplicity of investments (Ong 6). Investing in a home, in retirement, or in your community connects an individual citizen to larger public narratives of Americanism and national identity. This process produces complex affective entanglements that associate the private market with the public good and privilege the investment citizen as a primary subject position.

Citizens, organizations, and public officials all invoke the language of investment to justify expenditures on education, healthcare, green energy, the military, and more. Investment citizens are encouraged to invest financial and emotional capital—dividends they are promised will pay off later. Nebulous references to “the future” or “a better tomorrow” suggest that the affective power of investment is rooted in the ongoing relationship between the investor and the investment product. This relationship differentiates investment from consumption. The affective qualities of consumption are singular and bound to the act of consumption. While a payoff can be repeated with additional purchases, each act of consumption produces a singular, temporary reward. Investment creates an ongoing vested interest in a product or a public that “anchors people in particular experiences, practices, identities, meanings, and pleasures” (Grossberg 82). This affective remuneration continues for the life of the investment. Investment citizens often derive pleasure from the initial expenditure required for investment, but the potential for a return on the investment at the point of sale or redemption extends this feeling indefinitely.

Wendy Brown argues that an investment mode of citizenship reduces individual citizens to human capital (110). Citizens are no longer defined as members of a nation with guaranteed rights and freedoms. The imposition of market logic conflates the nation-state with the national economy. Traditional understandings of citizenship are subverted, and citizens must invest in the economic strength of a nation (an investment that will benefit them personally). Ultimately, Brown argues that modes of investment citizenship divorce the citizen from the public good. I argue that modes of investment citizenship, particularly those created by civic crowdfunding sites, allow the citizen to buy it. Investment citizenship does not deny the public good; it commodifies it. Using Neighborly as a case study in investment citizenship, I explore the way investment is emphasized for both personal and social solvency ultimately rearticulating the consumer citizen as an investment citizen and the public good as a private purchase that pays ongoing affective dividends.

Neighborly

The central image featured on Neighborly’s home page is a picture of small community drawn in monochromatic shades of green. The illustrated landscape includes a house, a library, a bank, a school bus, a fire truck, and several small trees. This quaint neighborhood scene is set against a backdrop of silhouetted skyscrapers and high-rise metropolitan office buildings. Visually, the illustration merges Wall Street with Main Street and rearticulates the abstract municipal bond market as something more concrete: a community with schools, parks, and, even though they are not pictured, people. Each illustration, from the fire truck to the school bus, invokes a shared ideal in which community members should invest. Smaller illustrations in the same style appear throughout the website. This imagined but familiar neighborhood is realized by photographs of similar scenes posted under descriptions of investment offerings in cities across America. Additionally, the website’s consistent use of green (the color of money) for the illustrations, text, links, and buttons is significant. With both color and image, the site interpellates visitors as both investors and members of a community.

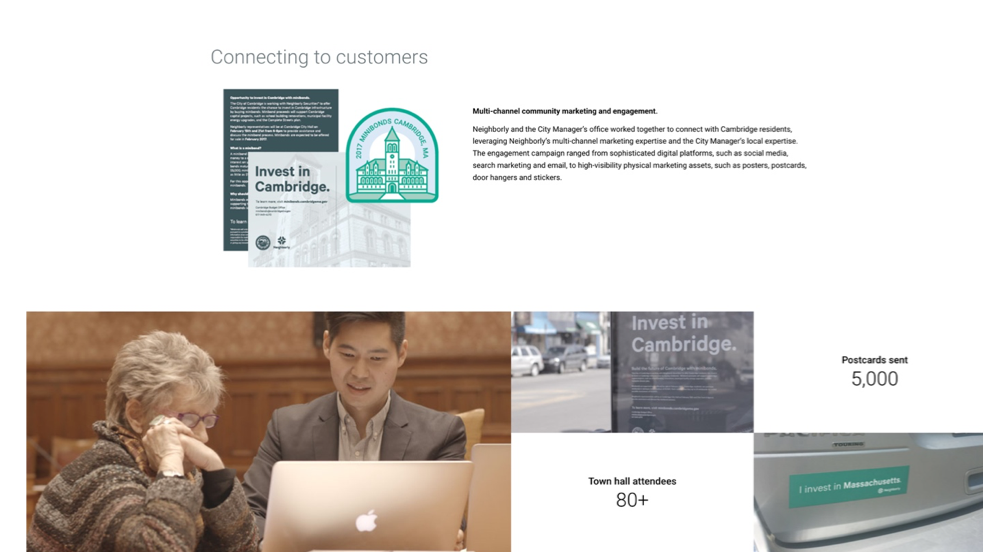

Rhetorically, Neighborly blends affective and financial investment. The site’s “Explore” page invites visitors to “invest in the future you want.” This emphasis on “the future” highlights the ongoing affective dividends that differentiate investment citizenship from consumer citizenship. Similarly, “the future you want” (emphasis added) encourages visitors and potential investors to approach the investment process with a sense of agency, a way to realize their financial and personal potential.2 Neighborly caters to individual investors, professional investors, and issuers, tailoring their message for each audience. Individual investors are encouraged to “invest in the places you live, work and play.” Professional investors are asked to “invest in impact.” Within high finance, “impact investment” refers to socially responsible investing (Gilbert). “Impact” assures investors that their money makes a difference. It feels concrete and consequential. Even messages targeted to issuers are overlaid with affective appeals to civic mindedness and financial solvency. Those looking to fund a public works project are reassured that financing with Neighborly will “empower your community to responsibly borrow what you need when you need it, with your constituents first in line.” Similarly, Neighborly refers to its service as “public finance,” suggesting both the social impact of municipal bonds and the publicness in this particular investment. The site frames the purchase of municipal bonds as an altruistic act that reflects a commitment to one’s fellow citizens. Cambridge, MA, the site of Neighborly’s first financial offering, circulated bumper stickers that said “I invest in Massachusetts.” Investing in Massachusetts is financial and affective, public and personal.

Additionally, Neighborly’s website refers to potential investors and even their own employees as “neighbors,” emphasizing the connection between the financial and civic sides of Neighborly’s project. Neighborly touts its employees as “a diverse, passionate team of civic-minded tech geeks and finance folks.” Describing themselves as “finance folks” rather than brokers or experts makes them seem more personable than a typical financial organization. Neighborly’s senior officers argue that part of their goal is to reinvigorate civic engagement (Field), and some outside observers suggest that the site’s platform might have such an effect (Cortese).

Neighborly argues that its real contribution is in “democratizing” investment by expanding access to municipal bonds, much like other crowdfunding websites that seek to democratize industries (Galuzka and Brzozowska). It invokes this idea both explicitly when it states its goal is “to democratize access to the 200-year-old municipal bond market” and implicitly with references to simplified investment, “grassroots financing,” and “increased transparency.” Founder and CEO Jase Wilson argues that “the financing of our nation’s places should be for, of, and by people like you.” He outlines his grand vision as follows: “We see a world in which anyone can invest in anywhere and places can borrow money to finance things they want and need directly from the community” (qtd. in Blanding).

Demystifying municipal bonds is another way that Neighborly improves access to these esoteric financial products. The site includes a “Learning Center” where visitors can take “Municipal Bonds 101” at “Muni School.” By enhancing citizen literacy of high finance and lowering barriers for purchasing municipal bonds, Neighborly claims to open up an avenue for average citizens to invest in their communities in a way that had been virtually impossible otherwise. Integrating personal profit with civic-mindedness has two important implications for the public’s performance of citizenship. First, Neighborly commodifies the public good (including essential services) as an optional investment product. Second, this commodification turns investment into a normative practice for citizens.

The advent of consumption citizenship and the imposition of neoliberal logic, Wendy Brown argues, erode citizens’ sense of themselves as “members of a democratic polity who share power and certain goods, spaces, and experiences” (176); however, Neighborly treats investment as a mechanism for establishing and maintaining affective connections between individuals and their community by suggesting that citizens can “build the future together” and encouraging visitors to “invest in the places and causes you care about.” Citizens who purchase municipal bonds can feel like they are helping their community while helping themselves. Neighborly makes this point explicitly: “Though your motivation may stem from a desire to increase your own personal wealth, by investing in municipal bonds, you’ll be supporting your city or town and potentially improving the quality of life it can offer its residents.” Personal profit and public good are bound together in these “feel good” investments.

When the public good becomes an investment product, purchasing municipal bonds becomes a mark of good citizenship. This financial investment is a necessary complement to the affective investment that citizens make in their communities. As Jase Wilson explains, this process has a strong history: “When we needed to build a ballpark or a school or a fire station or a library, we would gather around. We would vote the project in, and the next day we would buy bonds in our community.” Here Wilson constructs voting and investment as equivalent civic duties. Along this logic, good citizens invest in their communities, while those who do not (or cannot) are bad citizens.

Conclusion

Neighborly’s integration of a civic-minded sentiment with the purchase of municipal bonds extends the parameters of citizenship beyond the consumer citizenship of the 20th century into an investment citizenship of the 21st. Investing in municipal bonds helps cities and states meet their financial obligations while reflecting a communal impulse that serves as a model for other citizens. The normalization of investment as a marker of good citizenship alters the popular interpretation of both by conferring qualities of one onto the other. Additionally, the financial literacy that Neighborly teaches to potential investors certifies the purchase of municipal bonds as what Amy Wan calls “a marker of cultural citizenship” (5). Neighborly and other civic crowdfunding websites are cultural spaces that produce citizenship in terms of investment (Wan 6). In particular, Neighborly constructs a mechanism for producing good investment citizens both by making an impact investment product available for purchase and by offering citizens a path to financial literacy. Citizen investment, both financial and affective, in public works projects like those offered on Neighborly elides distinctions between the nation-state and the national economy. By introducing municipal bonds into the public market, Neighborly allows citizens to envision themselves as both good neighbors and good investors, and both are integral to the production of good citizens in a society where homo œconomicus compels citizens to actualize their citizenship through their investments.

Notes

- Examples include Spacehive, ioby, DonorsChoose, Citizinvestor, Co-City, and Neighborly. return

- An earlier version of the website even invoked Gandhi with the tagline “invest in the change you want to see in the world.” return

Works Cited

- Asen, Robert. “A Discourse Theory of Citizenship.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 90, no. 2, May 2004, pp. 189–211.

- Berlant, Lauren. The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship. Duke UP, 1997.

- Blanding, Michael. “Visible Hand.” MIT News, Feb. 8, 2016, news.mit.edu/2016/visible-hand-neighborly-jase-wilson-0208.

- Brabham, Daren C. “How Crowdfunding Discourse Threatens Public Arts.” New Media & Society, vol. 19, no. 7, July 2017, pp. 983–99.

- Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Zone, 2015.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. A Consumer’s Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. Knopf, 2003.

- Cortese, Amy. “Putting the Public Back in Public Finance.” The New York Times, 10 July 2015, sec. Business Day, www.nytimes.com/2015/07/12/business/mutfund/putting-the-public-back-in-public-finance.html.

- Delventhal, Shoshanna. “How Does Neighborly Work and Make Money?” Investopedia, 16 Feb. 2016, www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/021616/how-does-neighborly-work-and-make-money.asp.

- Farnel, Megan. “Kickstarting Trans*: The Crowdfunding of Gender/Sexual Reassignment Surgeries.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 2, 2015, pp. 215–30, doi.org/10.1177/1461444814558911.

- Field, Anne. “Municipal Bonds for the Rest of Us: A Startup Seeks to Democratize Public Finance.” Forbes, 30 Apr. 30, 2016, www.forbes.com/sites/annefield/2016/04/30/municipal-bonds-for-the-rest-of-us-a-startup-seeks-to-democratize-public-finance/.

- Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège De France, 1978-1979. Picador, 2010.

- Galuszka, Patryk, and Blanka Brzozowska. “Crowdfunding and the Democratization of the Music Market.” Media, Culture & Society, vol. 39, no. 6, Sep. 2017, pp. 833–49.

- Grossberg, Lawrence. We Gotta Get Out of This Place: Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture. Routledge, 1992.

- Hills, Matt. “Veronica Mars, Fandom, and the ‘Affective Economics’ of Crowdfunding Poachers.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 2, Feb. 2015, pp. 183–97.

- Hunter, Andrea. “Crowdfunding Independent and Freelance Journalism: Negotiating Journalistic Norms of Autonomy and Objectivity.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 2, Feb. 2015, pp. 272–88.

- Leonard, Andrew. “When Batman Isn’t Available: Crowd-Fund.” Salon, 11 Oct. 2013, www.salon.com/2013/10/11/when_batman_isnt_available_crowd_fund/.

- Nealon, Jeffrey. Foucault beyond Foucault: Power and Its Intensifications since 1984. Stanford UP, 2008.

- —. Post-Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Just-in-Time Capitalism. Stanford UP, 2012.

- Ong, Aihwa. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Duke UP, 2006.

- Pope, Adam R. “Bloodstained, Unpacking the Affect of a Kickstarter Success.” Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society, vol. 6, no. 2, 2017.

- Rao, Leena. “This Startup Wants to Modernize Public Finance.” Fortune, May 16, 2017, fortune.com/2017/05/16/neighborly-public-finance/.

- Sassen, Saskia. Losing Control?: Sovereignty in an Age of Globalization. Columbia UP, 1996.

- Scott, Suzanne. “The Moral Economy of Crowdfunding and the Transformative Capacity of Fan-Ancing.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 2, Feb. 2015, pp. 167–82.

- UNDP. “Impact Investment.” United Nations Development Program, n.d., www.undp.org/content/sdfinance/en/home/solutions/impact-investment.html. Accessed 12 Feb. 2018.

- Wan, Amy J. Producing Good Citizens: Literacy Training in Anxious Times. U of Pittsburgh P, 2014.

KEYWORDS: citizenship, investment, civic crowdfunding, Neighborly.com, municipal bonds

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: Municipal Courts and Community Center in Lake Mills, www.goodfreephotos.com/united-states/wisconsin/southern-wisconsin/municipal-courts-and-community-center-in-lake-mills.jpg.php

Blake Abbott is an Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Towson University. He specializes in rhetorical theory and criticism, public argumentation, political rhetoric, and cultural communication, particularly as they relate to questions of citizenship. His research focuses on the ways that rhetorical choices and public arguments in the aftermath of the economic crisis in 2008 have informed a shift in our understanding and performance of citizenship in traditional as well as more unconventional senses. In addition to Present Tense, he has published in Communication Quarterly, Argumentation & Advocacy, and The Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric.

Blake Abbott is an Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Towson University. He specializes in rhetorical theory and criticism, public argumentation, political rhetoric, and cultural communication, particularly as they relate to questions of citizenship. His research focuses on the ways that rhetorical choices and public arguments in the aftermath of the economic crisis in 2008 have informed a shift in our understanding and performance of citizenship in traditional as well as more unconventional senses. In addition to Present Tense, he has published in Communication Quarterly, Argumentation & Advocacy, and The Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric.