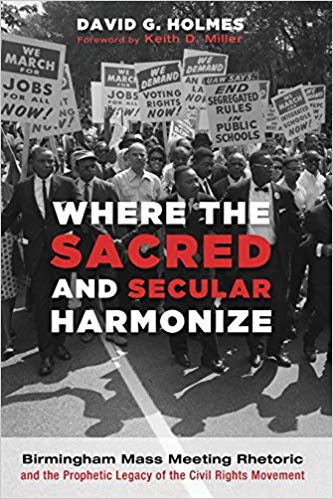

Book Review: Holmes’ Where the Sacred and Secular Harmonize

Holmes, David. Where the Sacred and the Secular Harmonize: Birmingham Mass Meeting Rhetoric and the Prophetic Legacy of the Civil Rights Movements. Eugene, Cascade Books, 2017.

Where the Sacred and the Secular Harmonize presents an in-depth and unique look at the work of various male speakers during the Birmingham mass meetings of the Civil Rights Movement. David Holmes details not only the relevance and importance of these speakers, but outlines the implications their prophetic style and messages had on the movement and, consequently, the relevance and implications such texts have on our society today. Holmes uses the frame of African American spiritual rhetoric to suggest his primary argument—that examining mass meeting rhetoric through a prophetic lens—will shed light on not only the power of religion at this crucial point in history, but will also reveal the motivation as well as the power behind many of the great and understudied speeches of the Civil Rights Movement.

Holmes defines prophecy as “a spiritual, moral, conceptual, and pragmatic orientation to speak truth to power, point out injustices, and defend the marginalized” (4). He uses Cornel West, David Chappell, and George Schulman as primary sources for framing his definition of the prophetic, and emphasizes in this framing the role of the African American church in both the Civil Rights Movement and, frankly, the emotional survival of African Americans at the time. Through sermons, Sunday school lessons, presentations, and in written materials, Holmes addresses the well-known rhetoric associated with these practices. He also points out that “African Americans rarely engaged in the ceremonial modes of communication simply to celebrate or pass the time; instead, they did so for some higher purpose: existential, social, political, cathartic—often all of the above, and almost always wrapped in the language of Christian spirituality” (8).

Holmes acknowledges the various disciplines at work in this study before providing specific examples of six “prophets” during the Birmingham mass meetings and their rhetorical contributions. He analyzes his speakers through a spiritual, social-justice oriented definition of prophetic, versus other traditional definitions that suggest foretelling or the deployment of the divine, and he addresses the importance of this lens in considering persuasiveness, effectiveness, and sheer motivation at a time in which to be bold and stand up for oneself came at such a high risk. Most importantly, however, Holmes feels that an emphasis on the prophetic will enhance not only our understanding of the concept of prophecy, but will provide a deeper understanding of the Civil Rights Movement. Holmes closes this text with a unique and honest interpretation of his own influences and inspirations for this work. These reflections tie together not only the importance of surveying such work, but the necessity in continuing the conversation.

The Six Speeches/Speakers

Holmes spends his first chapter framing the approach that he takes to analyze the six “prophets” he chooses to study. For the bulk of the text, Holmes conducts a rhetorical study of six pivotal speeches in the Birmingham mass meeting movement through this prophetic framing. The speeches Holmes analyzes are not always part of the typical narrative we hear in regards to the Civil Rights Movement, but Holmes uses them to address the varying ways in which they fulfill and espouse the idea of the prophetic.

In Chapter 2, Holmes focuses on Fred Shuttleworth, founder and president of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, to show that “the dividing lines between African American prophecy as poetry and prophecy as hermeneutics are neither indelibly nor easily drawn” (28). Shuttleworth intertwines the role of the prophetic and the strategy of hermeneutics primarily in his refashioning of the KKK acronym to stand for three prominent figures of the era whose last name began with the same initial: Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, and Nikita Khrushchev. Shuttleworth deployed this acronym at formal addresses as well as in informal remarks, and Holmes uses this as an example of Shuttleworth’s preaching to develop an apocalyptic storyline, indicative of both Black and prophetic preaching. By claiming the KKK as his own acronym, Shuttleworth meant to reclaim this strong source of fear and infuriate white segregationists. In this way, Shuttleworth deployed the portion of the prophetic that “defends the marginalized” (4) and used hermeneutics to energize and empower his audience.

Holmes next turns to James Bevel in Chapter 3 as a prophet for grassroots agency. Unlike Shuttleworth, Holmes identifies a particular speech Bevel delivered at a mass meeting on April 12th as “the groundwork for a grassroots prophetic rhetoric of mobilization whereby the black masses could recognize and exercise sociopolitical expression and agency with or without ministerial leadership” (51). Holmes sets the background for the speech by identifying traditional, revival-type patterns of most mass meetings. Unlike many of these other major speakers, Bevel used his platform to turn liberation into the responsibility of the people, asking “do you want to be healed?” and claiming that even some of the major leaders of the movement might be plagued by a sickness of passivity toward racism. Holmes uses Bevel’s examples of African American stereotypes and the frequent use of rhetorical questioning in his speech to emphasize Bevel’s role as a grassroots prophet. His prophetic voice therefore differed from the traditional rhetorical patterns of the mass meetings in its sense of both agency and urgency.

Holmes’s next prophet, Ralph Abernathy, is primarily known throughout history as King’s second-in-command, but Holmes focuses Chapter 4 on Abernathy’s power as an orator and a radical leader in the movement. Abernathy’s speeches are of a more informal vernacular, and he used humor, particularly in the May 3rd speech Holmes focuses on, to defend the narrative being told about the Civil Rights Movement. Abernathy points to police reports and other writings of the time that unfairly portrayed the work of his people. Through his use of AAVE and the call-and-response tradition associated with African American preaching, Abernathy subtly but clearly empowered his audience and consequently, the watching nation.

In Chapter 5, Holmes moves away from religionist rhetoric and focuses on who he terms “minor prophets,” James Farmer and Roy Wilkins. Though he continues to provide a background on both speakers and excellent context for the speeches delivered by these prophets, Holmes ultimately uses these examples to suggest that the idea of the prophetic was not inherently connected to the church throughout the Civil Rights Movement. Holmes suggests that Farmer’s primary tool throughout his May 2nd speech is laughter, which had a cathartic and inspirational effect. Holmes also addresses Farmer’s focus on his outsider status as a Northerner. This focus allowed Farmer to call into question and highlight the universal and nation-wide effect of racism. Wilkins, on the other hand, served as the president of the NAACP, and Holmes addresses much of the political tensions that surrounded this organization. Like Farmer, Wilkins too acknowledged himself as a visitor, which Holmes argues serves to lessen his leadership role and allows him to appear more approachable to his constituents. Holmes uses these two prophets to show the power in not only religious prophets, but secular ones as well.

Holmes’s sixth and final speaker is the most well-known prophet of the movement—Martin Luther King, Jr. This 6th chapter is where we see Holmes truly connect the power in prophetic rhetoric to contemporary issues, particularly in relation to the campaign, election, and presidency of Barack Obama. Holmes addresses King’s obvious prophetic status in the movement and draws connections to Obama’s prophetic role as the first Black president. Holmes identifies the driving force for much prophetic motivation—religion—and attempts to compare King’s very religious motivations to Obama’s more secular stance. More importantly, Holmes addresses King’s prophetic stance as one that is nearly unachievable, particularly by Obama. Holmes states that “by word and deed, Obama has been compared to a canonized, mythical MLK, one created and metamorphosed into the image of the conservative or progressive who happens to have been criticizing Obama at that moment. Obama was not the one who could not measure up. Black society can’t” (134). Here, Holmes examines the underbelly of the prophetic during the Civil Rights Movement and in present-day politics: no one, including King himself, can be true to the prophetic nature for which he is remembered. Holmes juxtaposes these interpretations of King’s character with specific examples from King’s and Obama’s speeches to reveal racial progress and muddy the lines between political and prophetic. We see here the limitations of Holmes’s definition of the prophetic, as well—the nature of the prophetic in all of these examples includes a reverence that is often canonized as sacred. However, through his analysis of the prophetic in minor and major Civil Rights players, Holmes shows us the underlying humanity of each of these speakers and their various styles of prophecy.

Holmes’s Personal Closing

Holmes uses his chapter on Obama and Martin Luther King Jr. to springboard into a deeply personal and contemporary reflection of the development of this book and the questions that remain unanswered. As with his examination of the prophetic throughout the text, Holmes identifies questions he faced throughout his academic and personal journey. He shares his own background and upbringing, reflections on his first few years teaching Civil Rights to students, and his formative fellowship throughout the American South. He then reflects on taking students to many of the places in which the book’s speeches were delivered. Finally, he points out the relevancy of understanding the role of the prophetic in social movements, citing Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, and the Tea Party. Though Holmes’s work reflects the historical lack of acknowledgement of the work of women and other voices in mobilizing the Civil Rights Movement, his personal testament reveals his connections to the prophets he chose to highlight. In each of these spaces, Holmes grapples with “the lines between marginalized personal experiences and traditional academic knowledge” (170).

Holmes reveals that academic can be personal, and that “objective” research should be not only relevant, but soulful work as well. He attests to the deeply personal elements of his identity as a Christian scholar, a Black man, and a teacher of young minds to his work and this project. This allows him to understand the power of the prophetic in his classroom and his life. Such honesty “connects the dots” between the prophets he studied, the power their rhetoric had on the movement, and on dialogues today. The use of his own story at the conclusion of the text provides a launching point for all readers into the personal nature of these conversations, and the legitimacy and relevancy of those personal stories to rhetorical scholarship. This honesty and use of narrativization provides a powerful framework in discussions centering around social change. In short, Holmes’s incorporation of the personal complements his examples of the historical, and allows us all to see the power of the prophetic in both sacred and secular spaces.

Conclusion

Holmes’s careful definition and explanation of the prophetic gives us a new understanding of the balance between the secular and sacred in speeches of the Civil Rights Movement. Additionally, his thorough rhetorical consideration of six of the major “prophets” and their iconic speeches allows us to see such a framing in motion, and once again provides a needed context for the work of the prophetic during such a formative time in history. Lastly, Holmes’s personal reflections allows us to consider current implications of studying the prophetic and the relevancy such rhetorical understanding has on conversations today. In Where the Sacred and Secular Harmonize, Holmes provides a scholastic exploration and personal examination of what it means to revisit research, explore rhetors, and reframe history as a means to answer one’s own questions about identity, social justice, and change-making.

KEYWORDS: spiritual rhetoric, rhetorical analysis, civil rights, hermeneutics, narration/story

Katie W. Powell is a Ph.D. candidate in the Rhetoric and Composition Program within the English Department at the University of Arkansas, as well as the associate director of student success with the University of Arkansas Honors College. Her research focuses on the ways in which communities remember, more specifically the problematic remnants of a community’s history such as confederate monuments and memorials. A white southerner herself, she is writing to understand the ways in which we perpetuate histories that a (white) community doesn’t want remembered yet cannot forget.

Katie W. Powell is a Ph.D. candidate in the Rhetoric and Composition Program within the English Department at the University of Arkansas, as well as the associate director of student success with the University of Arkansas Honors College. Her research focuses on the ways in which communities remember, more specifically the problematic remnants of a community’s history such as confederate monuments and memorials. A white southerner herself, she is writing to understand the ways in which we perpetuate histories that a (white) community doesn’t want remembered yet cannot forget.