The Crossing as Constitutional Rhetoric: Balsero Art and Identity from Cuban Refugee Camps and Implications for Cuban-American Relations

In 2014 Barack Obama changed the foreign policy of isolationism existing between the mainland of the United States and the island nation of Cuba. The White House’s Office of the Press Secretary issued the statement below on December 17 of that year:

Countless thousands of Cubans have come to Miami—on planes and makeshift rafts; some with little but the shirt on their back and hope in their hearts. Today, Miami is often referred to as the capital of Latin America. But it is also a profoundly American city—a place that reminds us that ideals matter more than the color of our skin, or the circumstances of our birth; a demonstration of what the Cuban people can achieve, and the openness of the United States to our family to the South. Todos somos Americanos.

This policy enabled Americans and Cubans alike to imagine a future water crossing without obstacles or checkpoints, even if, as Karl Vick described recently in Time Magazine, this policy only “nibbles at the edges of the embargo, which remains the law of the land” (35). As Americans consider this new relationship with Cuba, they may also reflect upon the more troubled crossings that characterize the journey from Cuba to Miami. Those crossing the Florida Strait were known as balseros (a word meaning rafters) who, as Obama describes in his White House press statement above, had only “the shirt on their back and hope in their hearts.” The Elián González case in particular highlights how the crossing of the Florida Strait—the passage between Cuba and Florida—has affected immigration policies and perceptions of political exodus. While many balseros fled the Castro administration in the 1990s to pursue US citizenship, Elián, a five-year-old Cuban boy, was the most famous balserito to arrive just months before the Bush/Gore election of 2000. His mother and stepfather had died upon crossing the waters between Cuba and Miami. Controversy reached its zenith when US federal marshals seized the exiled Elián from his remaining relatives’ home in order to return him to his father, leaving Cuban Americans feeling as if their dreams of a “young nation” rescued from Castro had been “shipwrecked” (“Saving Elián”). The boy’s arrival and sudden departure became a symbol of immigration policy gone sour; additionally, it characterized the Florida Strait as one in which innocent children may be pictured as exiles “clinging to an inner tube” amid “shark-infested waters” (“Saving Elián”), which relays the passionate feelings associated with survivors of the crossing.

As our relationship with Cuba evolves from a position of isolationism to one of “openness” (as Obama describes in his press statement), the consideration of how Cuban identity has been constituted by sea crossings seems especially important to our national consciousness. The image of families and children lost at sea, as was almost the case with Elián, holds a powerful place in the American imagination and has been a key trope in identifying and constituting Cuban refugees for decades. In this article, I look at the way balseros like Elián and others, in the midst of fleeing their home country and Castro’s reign, constitute themselves in a specific ideology when detained at Guantanamo Bay naval base in the mid-1990s. Here I draw upon a constitutive rhetoric approach explained by Maurice Charland to assist me in understanding how balsero children, many younger than Elián at the time he was transported back to Cuba, used visual rhetoric to reflect the idealized nature of their interrupted crossing to America. The photographs and pictures I share come from the University of Miami’s Digital Library archive titled “The Cuban Rafter Phenomenon: A Unique Sea Exodus.” These pictures, first displayed in the online archive in 2004 and created mostly by Cuban children, describe those living in the temporary camps at Guantanamo Bay just after they were apprehended by the US government. These refugees created drawings and graffiti on clothes in order to describe their experience in this “middle” space between the United States and Cuba.

Charland’s explanation of constitutive rhetoric originally applied to the rhetorical analysis of formal government documents, particularly in the case of French Canadians, the people of Quebec, who worked to articulate the constitution of a sovereign nation. In this article I intervene to suggest that constitutive rhetoric also frames and illumines the mundane, everyday creations of children, especially those whose life stories are shaped by exile and continual relocation. Although Charland’s ideas of constitution are based partly on the ideas of Kenneth Burke, who has already argued that “we must think of rhetoric not in terms of some one particular address but as a general body of identifications that owe their convincingness much more to trivial repetition and the dull daily enforcement than to exceptional rhetorical skill” (26), the documents Charland studies in his work rely on the imaginings and prose articulations of adult citizens embracing new identifications. Images from the archive, however, show how children—those unable to pen formal documents or fully articulate what exile means to them in a government white paper—paint their struggles of sea crossings in images just as compelling as those captured in written arguments. As Charland describes, the work of constitutive rhetoric has three main characteristics: the formation of a collective subject, the positing of a transhistorical subject, and the lack of free will associated with participation in a predetermined and fixed ending (141). This narrative frame may now be extended to Cuban children who similarly constitute and compose their balsero identity on material canvasses.

First, constitutive rhetoric establishes the collective subject’s point of view (Charland, “Politics” 617). Figure 1 shows that a child has written the name “balsero” on the canvas of a sneaker. Like many children wearing high-top sneakers in the late 1980s and 90s, this one has decorated the shoe with words and ideas like a peace sign and a heart with two sets of initials in it. These personal touches make the shoe a marker of identity as well as something to protect one’s feet. By writing the word “balsero” imprinted on her or his shoe, the child suggests that she or he is not just a balsero in the past tense but that she or he wishes to be hailed as a continual participant in crossing as a state of being. The child’s self presentation in such situations is a paradox if we consider the policy on immigration that once referred to dry feet versus wet feet. This “wet foot, dry foot” policy traditionally grants those Cubans who cross successfully and land on US soil the right to establish residence in Florida. Those who fail to achieve a successful crossing because of mishap or disaster at sea must return to their home country (Dooling; Silva). In the case of the shoe, the very act of standing on land grounds the exile in a community, however temporarily. But with the shoe comes a label that characterizes the owner’s foot as more than just a pedestrian but a swimmer or crosser of the sea. In this sense, the memory of wet feet constitutes, or identifies, the wearer as one who has earned the right to walk on dry land and call her/himself balsero.

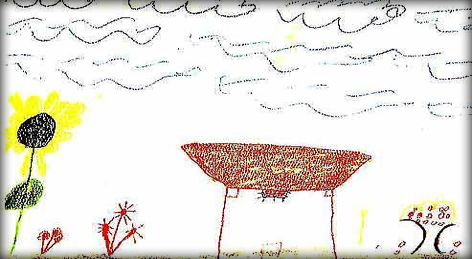

Drawings also constitute the balsero in a narrative that showcases the value of the raft as a source of protection and shelter. Figure 2 shows a child’s drawing in which a raft acts as a roof for a structure, or possibly a shelter, on land. The boat is not floating in water but is propped on two poles and empty of cargo. Still, in the midst of the landscape, the boat is central. The flowers, soil, and clouds surround it and make it the central focus. Even on land, the boat itself remains the dominant object; it is the means by which the balseros are always, as Charland says, “teleologically moving towards emancipation” (144). The boat held aloft on dry land illustrates the paradox within which the exiles lived—both as residents and refugees detained in their passage to Miami. They existed, as Erik Doxtader in his work on the rhetorical middle has articulated, between dissensus and consensus. The boat as shelter and tool for future passage is indicative of how “everywhere and nowhere, middles are hard to define” (338). Middles become important spaces for discussion because, as Doxtader further argues, “civil society becomes vulnerable to extremism and insensitive to the nuances of public interaction” as it stresses beginnings and endings (338). Balseros followed US orders by remaining at the camps in Guantanamo while still contesting the political world of their homeland. This state of passage, or crossing, places Cubans in the middle of their experience to gain US citizenship. We tend to overlook this middle experience and favor more extreme representations of disaster, such as photos or descriptions of balseros who died at sea. This lack of attention toward the middle, where they remain in a time of waiting, costs us insight into how balseros shape their identity.

Children’s art from Guantanamo also depicts the dream of freedom as possible but illusory since chains and fences barricade the way (see Figure 3). The water itself is not a source of anxiety or separation from the United States, even though crossing it is dangerous. Here, barbed wire, not water, separates the refugee from freedom, or “libertad,” which the child artist crosses through in dark black ink. As depicted here, a person seated in a manmade chair is far more enclosed than one who finds herself on dangerous waters on a makeshift raft. By accepting the trappings of domesticated living, the possible becomes less probable for those who forget their original goal of crossing. In constitutive rhetoric, the narrative provides a scene of action for those who struggle to achieve a goal; Charland says it is “orienting them towards action” (143), while Burke in A Grammar of Motives explains that constitution works in part because we see how the present is charged with futurity (336). This idea places great emphasis on the value of the drawing because it reveals how balseros view the middle experience as an obstacle to the ending, represented by the brown terra firma in the horizon. If the present is charged with futurity, then, as Burke says, it is harder to see “around the edges of our customary perspective” (335); and, for the balsero, becoming a domesticated resident of the camps means compromising the chance of a successful crossing. As he sits, freedom remains behind him and distant—not before him and easily obtained. Residence, however temporary, in Guantanamo becomes a narrative detour that tempts the Cuban refugees into complacency and sidetracks the original journey, even if they are originally held there against their will. Once seated and complacent, the man above in the drawing fails to orient himself toward action, and, therefore, he remains behind. The child artist accurately captures what would have been a common fear for all balseros of this particular time.

However, the balsero narrative includes symbols that comfort them during their time in limbo at Guantanamo. Hints of religious iconography seem to appear in artifacts that young balseros left behind, particularly in one image from the University of Miami’s Digital Collection.

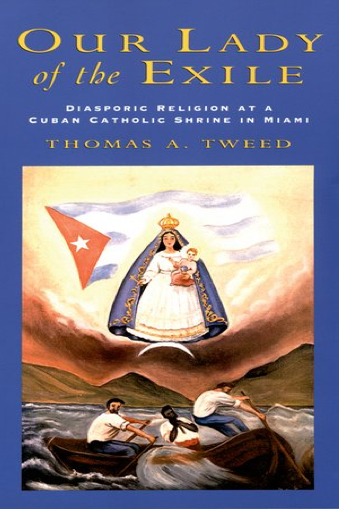

In Figure 4 the artist drew a triangular rainbow trapped by barbed wire. In this picture, the rainbow takes the form of a shape reaching toward heaven with a star at its top. Many pictures of the Virgin Mary, known as the Lady of the Exile to Cubans, show her in this same triangular shape, reaching toward the heavens, wearing a colorful blue coat that, when opened at the base, forms a triangle with her body (see Figure 5).

Rafters often take the Catholic image of Mary the Virgin as a safeguard against harm during the crossing between Cuba and Miami. The cover art on Thomas Tweed’s monograph in Figure 5 provides a common representation of Mary as Our Lady of the Exile, a title associated with her shrine in Miami, Florida. This title references the statue’s own exile from Havana when she was delivered by plane to the US mainland in 1961. Over time, the shrine of Our Lady in Miami became a place where former refugees gathered to honor their heritage and their crossing. In this sense, the theological symbol of the Virgin is a transhistorical one because she links balseros across generations through the shared values of Catholic faith. She helps establish a narrative like the one Charland explains in his work on the Quebeçois. In his study of the white paper produced by these people, he argues that the founding of a nation creates a linear movement toward emancipation. Likewise, Mary’s (or the statue’s) position as a lady in exile enforces the premise that in constitutive rhetoric the subject “exists beyond one’s body and life span” (143) and may be linked to historical events happening across decades. For many, she was considered by Cuban Americans to ally herself with balseros, even if she was not transported by raft to Miami. Instead, she represented and continues to represent for Cuban Americans the fortune of a successful arrival on US soil; however, the Miami shrine itself also faces Cuba and the sea separating families from their homeland (101), thereby making it an object associated with diaspora.

Miami Cubans rallied around Mary as a way to unify their identity after leaving their homeland. During the crossing, even those considered “unchurched” or separated from religion would offer private prayers to the Virgin for a safe arrival and would carry an image of her in their wallets (Tweed 28-29, 32). While it is impossible to prove whether Figure 5, the child’s drawing, was based on the Virgin’s shape, the children at the camp would have been familiar with multiple images of her during their stay and may have been influenced by the colors and shapes associated with her. In most images, the Virgin’s placement echoes the placement of this rainbow in its reaching toward the heavens. For those detained at Guantanamo, the Virgin, who would protect them in a crossing, could not free herself from the same wires that trapped the exiles. In this sense, the Virgin and the people detained become the same collective subject, one that reaches across time.

Both terms,“crossing” and “constitution,” represent processes in which the completion or ending of a narrative becomes secondary to the unfolding or continual progression of a people’s history. The act of constituting, as explicated by Burke and by Charland, helps to characterize what happens as a journey becomes the identifying marker of a group seeking a new life. As Charland stresses in his work, “if it is easier to praise Athens before Athenians than before Laecedemonians, we should ask how those in Athens come to experience themselves as Athenians” (134). What is remarkable about the children’s art is the wealth of ideological and political insight that helps us understand what it means to be a balsero. Charland explains that often, at the start of life, “our first subject positions are modest, linked to our name, our family, and our sex,” only becoming more complex as we approach adulthood (147). Balsero children, subjects we might consider naïve or inexperienced in worldly matters, challenge this idea with their drawings: their art reflects what it means to exist in the political middle of national upheaval and help us understand how an exiled people identified themselves.

In the movement from and to a place, the identifying markers that characterize a community’s participants hold rhetorical meaning beyond a specific moment or individual case like Elián González. Especially today, as the United States and Cuba move toward a more open version of this famous passage, the story of rafters detained in Guantanamo represents a unique contestation of national identity that exists in the spaces between a journey’s beginning and its end. The drawings made by children are one way to glimpse this particular moment as a testament to crossings as constitutive of what it means to be a balsero. The art represents a struggle with identity that continues to this day since the island of Cuba remains both proximal to but separate from the US mainland that once denied many residents entrance into Miami. While options for travel to Cuba increase for Americans, the preservation of history associated with the water passage becomes even more important since, to put it mildly, “cultural miscues” between Cuban and American citizens are likely results of future tourist invasions (Elliot). Today’s political climate represents another “middle” for the US and Cuba, one characterized by anticipation but also lingering suspicions.

All images appear courtesy of the Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida.

Works Cited

- Burke, Kenneth. A Grammar of Motives. Berkeley: U of California P, 1945. Print.

- —. A Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: U of California P, 1950. Print.

- Charland, Maurice. “Constitutive Rhetoric: The Case of the Peuple Quebecois.” Quarterly Journal of Speech. 73 (1987): 133-50. Print.

- —. “Politics.” Encyclopedia of Rhetoric. Vol. 1. Ed. Thomas O. Sloan. New York: Oxford UP, 2001. 617-18. Print.

- “The Cuban Rafter Phenomenon: A Unique Sea Exodus.” University of Miami Digital Library. Web. 1 May 2014.

- Dooling, Maria.“Twentieth Anniversary of the Cuban Rafter Crisis.” University of Miami Libraries Cuban Heritage Collection. 1 Aug. 2014. Web. 27 April 2015.

- Doxtader, Erik. “Characters in the Middle of Public Life: Consensus, Dissent, and Ethos.”Philosophy and Rhetoric. 33 (2000): 336-69. Print.

- Elliot, Christopher. “What Americans Should Expect When Traveling to Cuba.” Fortune. 14 Aug. 2015. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

- Heath, Robert. “Identification.” Encyclopedia of Rhetoric. Vol. 1. Ed. Thomas O. Sloane. New York: Oxford UP, 2001. 376-77. Print.

- “Saving Elián: A Timeline.” Frontline. PBS. Feb. 2001. Web. 15 Apr. 2015.

- Silva, Cristina. “Illegal Immigration 2015: Immigrants from Cuba Can Continue ‘Wet Foot, Dry Foot’ Policy, Says Obama Official.” International Business Times. 24 Feb. 2015. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

- “Statement by the President on Cuba Policy Changes.” The White House. 17 Dec. 2014. Web. 23 Mar. 2015.

- Tweed, Thomas. Our Lady of the Exile: Diasporic Religion at a Cuban Catholic Shrine in Miami. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997. Print.

- Vick, Karl. “Cuba on the Cusp.” Time Magazine. 185. 12 (2015): 28-39. Print.

Shannon Howard is an assistant professor at Auburn University Montgomery and the Director of the Master of Teaching Writing degree. Her recent work has been featured in Journal of American Culture, Studies in Popular Culture, and Pedagogy. Her research interest focuses primarily on material rhetorics as they are experienced in communities, popular culture, and pedagogical settings.

Shannon Howard is an assistant professor at Auburn University Montgomery and the Director of the Master of Teaching Writing degree. Her recent work has been featured in Journal of American Culture, Studies in Popular Culture, and Pedagogy. Her research interest focuses primarily on material rhetorics as they are experienced in communities, popular culture, and pedagogical settings.