Reappropriating Public Memory: Racism, Resistance and Erasure of the Confederate Defenders of Charleston Monument

No memory is possible outside frameworks used by people living in society to determine and retrieve their recollections. ~ Maurice Halbwachs

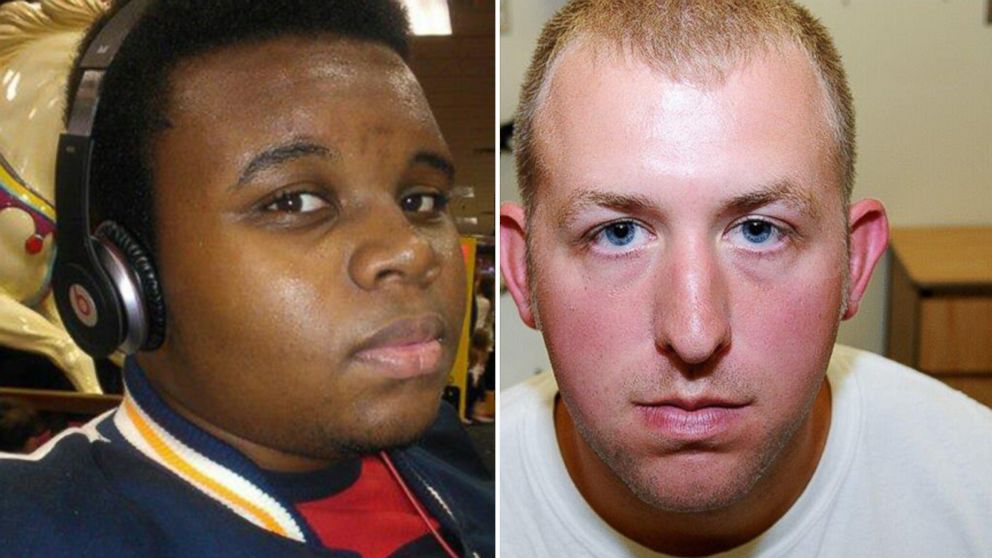

As of 2015, the question of whether #blacklivesmatter has been proclaimed publicly in response to a tragic string of murders, starting with the death of Michael Brown in August 2014 and moving most recently (as of this writing) to Charleston, where a self-proclaimed White supremacist killed nine Black people in a church. These events hearken back to the long history of violence against Black community members; indeed, in the relatively short history of the United States, the torture and killing of Black citizens has been disturbingly prominent, though perhaps all-too-quickly fleeting, from White mainstream America’s memory. The recent tragedies serve as a reminder of the past’s presence, and the #blacklivesmatter movement signals an effort both to resist the racist politics of the 21st century and to remember Black struggles. We, too, want to address memories and remembering, particularly as they are memorialized through monuments. Monuments function to collect public memories and to erase, coalesce, and homogenize individual memories. Monuments hold up a mirror to the community, telling them not just who they were but who they will be (Hatskins; Johnson).

The importance of public memory and monuments has been particularly clear in the wake of a terrorist attack at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church. The nine victims of the attack—Reverend Clementa Pinckney, Reverend Charanda Singleton, Reverend Daniel Simmons, Cynthia Hurd, Sharonda Singleton, Myra Thompson, Tywanza Sanders, Reverend DePayne Middleton-Doctor, Susie Jackson, and Ethel Lance [we say their names]—were shot and killed by a White supremacist during a Bible study. The Charleston shooting caused outrage throughout the nation, but, in Charleston, peaceful vigils, open forgiveness, and prayer services marked a contrast to the more rancorous responses seen in Baltimore after Freddie Gray’s death and in Ferguson, MO, after Michael Brown’s death.

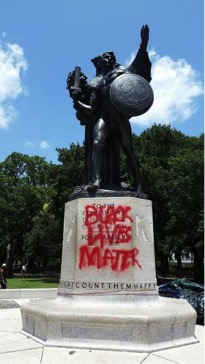

Discourse surrounding the rampant Confederate pride of South Carolina, however, appeared less forgiving. The long history of violence against the Black community remains memorialized across the state, where the Confederate flag continues to fly1 and where monuments to the Confederacy still stand. One such monument is the Confederate Defenders of Charleston (CDC), erected in 1932 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Hermon MacNeil sculpted the statue as a dedication to the Confederate soldiers who defended Fort Sumter. The statue, nearly thirteen feet tall, depicts a soldier with his shield posed in front of his wife, standing on top of a base (“Confederate Defenders”). Until Saturday, June 20, the base read “To the Confederate Defenders of Charleston,” and below it read “Count Them Happy Who For Their Faith And Their Courage Endured A Great Fight.” For several hours on June 21, however, the monument’s original inscription was illegible, having been spray-painted over (allegedly by protesters) with “Black Lives Matter” on one side of the monument’s base and, on the other side, “This is the Problem #Racism.” This version of the monument lasted only a few hours before city workers covered the spray-painted portion of the statue with a tarp, leaving the soldier and his wife visible and protruding from the cover.

For a few brief hours, the public memory of Charleston’s Confederate history (represented by the CDC monument) was materially reinscribed as part of the #blacklivesmatter movement. In this article, we consider this act and its impact on the #blacklivesmatter movement, particularly as an act that shapes and reshapes public memory. Because public memory forms (and constantly reforms) through material and rhetorical means, such an analysis offers US rhetoricians a way to consider our own public memory and identity as it is tied to the history of violence against Black people. We analyze the CDC as an act of racism and the spray-painting as an act of resistance and then question the efficacy of that resistance, given the tarping (erasure) of the spray-paint. The now half-statue represents a new public memory, but what, if anything, has been changed or erased? Might we consider the “Black Lives Matter” inscription as its own memorialization? Can we read the tarping of the monument as a racist act, wherein the state acts on behalf of its racist history by covering up the “Black Lives Matter” resistance?

The Rhetoric of Public Monuments

Public monuments serve as rhetorical and material renderings of public memory, wherein, as James Young suggests, not only is public memory constructed but events are co-constructed with memories and monuments. We follow Young’s argument that there are “worldly consequences in the kinds of historical understanding generated by monuments,” and our analysis seeks to understand the consequences of the CDC monument, its subsequent defacement, and the state’s final act of erasure (15). The consequences of this act, we think, are more pronounced because of the racialized nature of the monument and contested memory it accompanies. As Paul A. Shackel and other scholars note, sites of memory that become contested are typically racialized ones, so we pinpoint how activists reappropriated the contested memory of race for their own movement (173-4).

Other recent scholars establish Shackel’s point through writing about specific monuments that represent racial complexity. Victoria J. Gallagher and Margaret R. LaWare, for example, challenge the racial interpretation of the Monument of Joe Louis located in downtown Detroit, arguing that this (and other monuments with racial value) remain “complicated” and “unfinished” due to the multitude of interpretations from various audiences (102). Racialized material objects are constantly being rewritten and revalued by different audiences who either visit the site or, to draw on Laura Gries, see circulated (and/or iconic) images of the site. Kristan Poirot and Shevaun E. Watson address Charleston more specifically and suggest that racialized material objects there are particularly important because the city’s tourism practice eschews its potential to resist White supremacy. Though the authors see potential for “characterizations of black agency that offer a new perspective of the antebellum South, the rhetorical labor performed through its tourism imaginaries circumscribes this potential to commemorate and celebrate the living manifestations of racial hierarchies” (111). The CDC, as both a complex and racialized site of public memory, provides a rich text for rhetorical study, even more so given the reappropriation of the site through defacement.

Acts of Racism, Resistance and Erasure: #blacklivesmatter

Rhetorically and materially, the CDC functions (like other monuments) as a state-sanctioned reminder of history—but not just a reminder; it is also a celebration, a dedication, a way of honoring Confederate soldiers. As such, the CDC memorializes and celebrates a racially complex history, wherein the Confederate soldiers fought to maintain the institution of slavery, violence against Blacks in the country, and the racism that extends from and motivates both. Further, as a state-sanctioned monument, the CDC represents the state’s endorsement and, perhaps, shared celebration of the Confederate effort. The monument signifies the South and Charleston as “defenders” from northern aggression, adopting Confederate ideologies and suggesting that those ideologies are worth defending. The title of the statue invites visitors to identify with the righteousness of the Confederacy and to associate with the ideologies it represents. Although Confederate commemorations draw many White men and women to revere the Confederate legacy, Manuel Roig-Franzia notes that this kind of celebration “[is] not black Charleston’s event. Its leaders [shun] the festivities and [denounce] its purposes.” For protestors of the #blacklivesmatter movement, like the rest of Black Charleston, the statue signifies a pain of the past living and thriving through contemporary commemoration.

Although the CDC memorializes the Confederacy as a brave, noble, and valiant organization, for many others, this memory of the Confederacy is distorted: who would celebrate those who hoped to sustain the institution of slavery, replete with its violence and dehumanization of African-Americans? And so it follows that, in the wake of the Charleston shooting and as part of the #blacklivesmatter movement, this contestation would formulate materially.

After activists tagged the CDC with the inscriptions “Black Lives Matter” and “This is the Problem #Racism,” images of the monument circulated through news rounds. Through spray-paint, activists took back the memory of the Confederacy and reappropriated the symbolic value of the statue in favor of Black history, creating a “Black agency” and a more nuanced understanding of how people of color view Confederate monuments. By spray-painting the base of the monument and covering up its title, activists reinterpreted it; no longer the heralded symbol of Confederate pride, it became a new a symbol of Black history. In its original conception, the CDC erases the history of slavery and the violence of the Confederate mission. But with these new spray-painted sayings, the activists make the CDC represent their history, too, inscribed into the sides of the monument in red letters. The spray-painted quips create a new historical moment for the Black community, insisting that their history will be witnessed in front of White history. Yet the swift move to cover up the homage to Black history and Black lives complicates the resistance.

If spray-painting reappropriated the monument, making the CDC something quite other than a state-sanctioned Confederate celebration, what do we make of the hasty work of the city to cover up—not the entirety of the statue—but only the parts that had been “defaced?” By taking back the statue with a dank, gray tarp, the city sought to silence the protest and recover their White(washed) public memory. Contested sites of public memory are often silent2; however, in this instance, viewers know the discord is present, but the tarp attempts to cover the pain through erasure.

The need to cover up the conflict could be read in a number of ways. First, as in other cases of racial dissonance, the cover-up implies White America’s insistence that even when the Black community is victimized by the state, it ought to follow the rules of the state. Cries from White folks regarding the Ferguson protests, for example, sought “peace” and admonished any betrayal of the governing laws. Many White people likewise view the act of defacement as “criminal” and unjust. Second, the tarp also symbolizes erasing the public memory brought forth by the “Black Lives Matter” inscription. The red spray-paint brought a new perspective of the Confederacy and its racism into light. Since monuments seek to homogenize memory, the competing inscription was erased in order to maintain the city’s sense of orderly racism. We might, alternatively, assess the tarp as not just a rejection of the alternative perspective but as a renewed celebration of the Confederacy—not just an erasure of the idea that #blacklivesmatter but a declaration that, in fact, Black lives will never matter as much as the White lives that sought (unsuccessfully) to maintain the subjugation of slaves.

But we argue that these interpretations are not so simple. The covering up of the inscription, whether for compliance with the state, erasure, or racist celebration, creates a palimpsestic memory through the monument. Even if restored to its original state, the monument will never be the same, just as public memory of the monument will never be the same. The material of the paint shaped and shifted the original material, pulling at it, resisting it, drawing it away. Further, the reproduction and circulation of the image of the defaced CDC positions the reappropriation discursively as an act of resistance that cannot be erased. Finally, regardless of what happens, the local act, performed by an unknown number of people, will have an affective ripple effect. Even the mere circulation of CDC 2.0 resulted in other acts of resistance, including (presumably) activists defacing Confederate monuments in St. Louis, Baltimore, and Richmond. Indeed, while the tarp seeks to cover up the act, the rhetorical work of public memory is such that the resistant act will not be erased, though the monument has been covered up.

Conclusion

Given that more than half a dozen monuments have been tagged since this original incident, it stands to reason that more Confederate relics will be desecrated in the future (Salter). Even social justice sites like Fusion have called for crowdsourcing to map national statues of the Confederacy in order to promote their erasure and reappropriation (Hogan). For many activists, tagging these Confederate sites of contested memory affords the opportunity to recreate public memory as one that understands and empathizes with Black social justice issues.

Our brief analysis calls on rhetoricians to address and engage with the Black Lives Matter movement in new ways, embracing and engaging with public memory and affect as central to the rhetorical moment; even without the monument, the #blacklivesmatter movement continues to re-invite and recreate public rhetoric in part through shaping public memory. Public memory, as many scholars have written, shapes identity and values, and with each new act of defacement, with each new etching of “Black Lives Matter” on monuments and other sites, activists rewrite the public memory of these sites as a more complete symbol of reality: representing not just the Confederacy or Black struggles for humanization but the need for contesting injustice. Acts of “vandalism” and activism alter the perception of history, contesting our past and present, and illustrate that systemic racism pervades American culture from various viewpoints.

While Americans generally visit historical landmarks and sites of memory to better understand their past, defilement of these structures challenges mainstream accounts of history and produces a more accurate depiction of what these sites represent. In this historical moment, as the Black Lives Matter movement surges to the forefront of American politics, materially changing these statues not only generates a more nuanced view of history but also rewrites the narrative of Black people back into these sites. Indeed, as we respond to Gries’s (2014) call for drawing together affective and visual rhetorics, we also tend to the ways the Black Lives Matter movement and its rhetorics help to form public memories and illuminate the ways public memory can shift and be altered as well.

Endnotes

- At the time of this writing, the public debate surrounding the Confederate flag is prominent; Bree Newsome has just recently removed the flag from its position in the capital, and many government representatives have spoken openly about the need to remove the flag. So it may be (we hope) by the time this goes to print, the flag may no longer fly in South Carolina. return

- Sites of memory that are often contested typically are not marked by this contestation and are thus “silent,” only demonstrating the hegemony’s interpretation. For instance, monuments to Jefferson Davis often glorify his “character” but fail to describe his thoughts on slavery. Audiences might express disagreement with this interpretation of his remembrance, but the edifice only contains this one viewpoint, silencing opposing voices. return

Works Cited

- “Battery and White Point Gardens.” Discover South Carolina. South Carolina Office of Tourism, 2015. Web. 23 June 2015.

- “Confederate Defenders of Charleston.” The Historical Marker Database. The Historical Marker Database, 2015. Web. 24 June 2015.

- Gallagher, Victoria J., and Margaret R. LaWare. “Sparring with Public Memory.” Places of Public Memory. Eds. Greg Dickinson, Carole Blair, and Brian L. Ott. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2010. 87-112. Print.

- Goudeau, Ashely. “Confederate Statues Tagged with ‘Black Lives Matter.’” USA Today. USA Today, 24 June 2015. Web. 24 June 2015.

- Gries, Laurie. “Iconographic Tracking: A Digital Research Method for Visual Rhetoric and Circulation Studies.” Computers and Composition 30.4 (2013): 332-48. Print.

- Hatskins, Ekaterina V. “Russia’s Postcommunist Past.” Global Memoryscapes. Eds. Kendall R. Phillips and G. Mitchell Reyes. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2011. 49-79. Print.

- Hogan, Patrick. “Help Us Map the Last Remaining Monuments of the Confederacy.” Fusion. Fusion Media Network, 23 June 2015. Web. 24 June 2015.

- Johnson, Nuala. Ireland, the Great War, and the Geography of Remembrance. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

- Poirot, Kristan, and Shevaun E. Watson. “Memories of Freedom and White Resilience.” RSQ 45.2 (2015): 91-116. Print.

- Roig-Franzia, Manuel. “Charleston’s Confederate Defenders Are Lauded.” The Seattle Times. Access World News, 18 Apr. 2004. Web. 23 June 2015.

- Salter, Jim. “Vandals Target Confederate Monuments.” Yahoo. Associated Press, 26 June 2015. Web. 26 Jun. 2015.

- “Slavery in Charleston and the Lowcountry.” International African American Museums. International African American Museums, 2012. Web. 23 June 2015.

- “White Point Garden.” Palmetto Carriage. Palmetto Carriage Works, 2015. Web. 23 June 2015.

- Young, James E. The Texture of Memory. New Haven: Yale UP, 1993. Print.

Cover Image Credit: @RobertMaguire, Twitter

James Chase Sanchez is a doctoral candidate in Rhetoric and Composition at Texas Christian University and a member of the NCTE/CCCC Latin@ Caucus. His dissertation examines the public memory and identity construction of residents in his hometown of Grand Saline, TX, as catalyzed by an elderly, white preacher’s 2014 self-immolation in protest of the town’s racism. His work has appeared in Steinbeck Review, the Journal of Popular Culture, and Studies in American Culture.

James Chase Sanchez is a doctoral candidate in Rhetoric and Composition at Texas Christian University and a member of the NCTE/CCCC Latin@ Caucus. His dissertation examines the public memory and identity construction of residents in his hometown of Grand Saline, TX, as catalyzed by an elderly, white preacher’s 2014 self-immolation in protest of the town’s racism. His work has appeared in Steinbeck Review, the Journal of Popular Culture, and Studies in American Culture.  Kristen R. Moore is an assistant professor of technical communication and rhetoric at Texas Tech University. She researches public rhetoric and technical communication, focusing specifically on the ways that diverse communities might be served by critical theories, inclusive rhetorics, and activist scholarship. Her articles have been published in the Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, the Journal of Business and Technical Communication, and Learning, Media, and Technology.

Kristen R. Moore is an assistant professor of technical communication and rhetoric at Texas Tech University. She researches public rhetoric and technical communication, focusing specifically on the ways that diverse communities might be served by critical theories, inclusive rhetorics, and activist scholarship. Her articles have been published in the Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, the Journal of Business and Technical Communication, and Learning, Media, and Technology.