Embracing the Messy Business of Learning: Serving Multiple Stakeholders in a Technical Communication Internship

Introduction

For those providing internships as part of their curricula in rhetoric and writing studies, teaching the processes of working through an internship can be challenging: there is not one process but potentially many.1 The constraints of the coursework—resources and time—add to the practical approach of teaching a linear process: learn skills throughout your coursework, find an internship, produce a deliverable needed by your client, get a grade. However, there are many things faculty and students may not anticipate as the structure of the curriculum and the pedagogy might not reflect the very messy, recursive, discomforting approaches taken by various and sometimes unexpected stakeholders in internships and other workspaces. While in the classroom we provide students with instruction in working with multiple clients—especially in the case of experiential learning opportunities, the actual internship may not be so straightforward (Bosley). How should a student respond to the multiple factors affecting the work they must accomplish with various stakeholders?

In this case study, we describe a process of one author-intern’s work negotiating with multiple stakeholders to successfully complete her internship. While acting as an author-intern for the client, a rural community health center, the student also served as a conduit for information amongst primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences.2 Even with the proper training in the use of production tools and best practices for interacting with clients, our student still needed on-the-job training to understand the highly recursive nature of the work she undertook (Little). We argue that while we as instructors cannot prepare students for every possible situation they may encounter, we can prepare them for the complexities that arise in working with real-world clients by teaching them flexibility in approaching this type of work—that is, a process in which there are multiple processes. Ultimately, with such an understanding, students in internships serve as professional writers by employing rhetorical skills that allow them to work as equal partners with their workplace constituents.

Methods

In the summer of 2011, a student in our graduate technical communication program undertook work with a rural community health center in Virginia as an author-intern. The health center had implemented a program using community health workers (CHWs) as a means of serving its clients. Members of the public who provide basic medical care to their community, CHWs act as liaisons between local healthcare consumers and their providers. While not formally trained in medicine, CHWs receive training in basic medical care. Their primary responsibility is to reduce clients’ unnecessary visits to emergency medical facilities by providing them medical advice and healthy-living education (Witmer et al.). Providing specialized and general care to a wide range of individuals, today’s CHWs must accommodate linguistic and cultural differences when interacting with and treating clients, training their own clients not only in medical treatment but also in the best ways to use CHWs as a resource.

A goal of the CHW program is to empower underserved populations to take control of their own health decisions. One method of helping these populations is to design communications specifically for the clients’ needs. In this case, the CHW program wanted a brochure to explain the services they offered to underrepresented populations. Though not trained in brochure design, the author-intern used the workplace as a way to learn the conventions of that genre. The conventions go beyond simply the linguistic; she must rely on the CHWs to understand the cultural significance of the communication and how it can help empower the client to use the CHW as an appropriate resource for the client’s own basic medical needs.

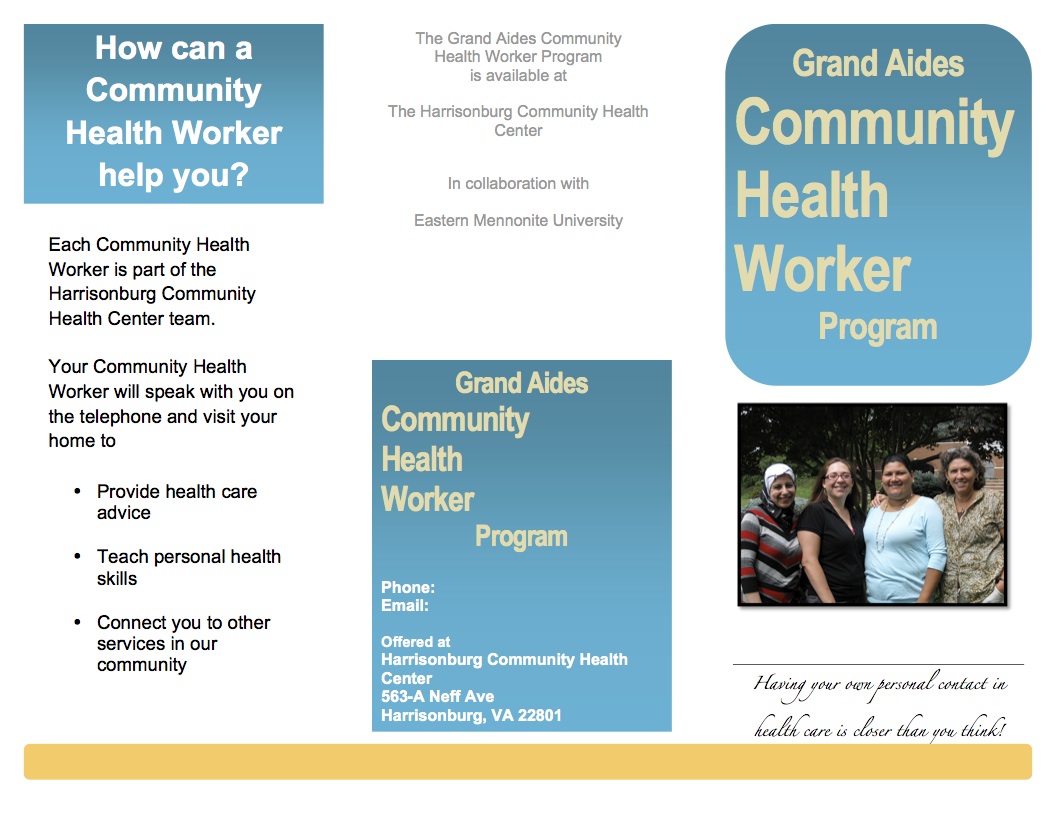

The author-intern took on this task as part of her graduate internship, developing five brochures: one general English-language brochure for the health center; and four customized brochures, one for each of the community center’s CHWs, in both English and a second language specifically intended for the clients of individual CHWs, either Spanish or Arabic. While the author encountered issues of design and layout when creating the brochures, the biggest hurdle was localizing the contents of the individual brochures for their intended audience. Even though the CHWs who were native speakers translated their brochures into a second language, the author-intern worked with them to accommodate the cultural expectations of the audience when writing the English version of the brochure.

To understand the purpose, audience, and scope of the brochures, the author-intern first met with two representatives who coordinated the CHW program: the community health center marketing director and CHW program director. During an early meeting between the author-intern and CHW program representatives, the latter established these needs for the brochures and the identity of the program. For example, the marketing director outlined the identity and mission of the community health center; the CHWs’ brochures include this information, as well as its market identity, legal wording, and style (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). As the program was relatively new, neither the CHWs nor the community health center had existing marketing materials. The program representatives decided that a general brochure and personalized brochures would serve different purposes. Health center staff would provide potential participants in the CHW program with the general brochure. CHWs would then use the personalized brochures as an introduction to and a reference for their clients.

Once the purpose and audience for the brochures were established, the author-intern created a draft of both the general brochure and a basic outline for the personalized brochure. An initial meeting with each CHW helped form an idea of who the CHW’s clients were and how she interacted with them. To prepare for this meeting, the author created a list of questions designed to encourage the CHW to discuss how the brochure could be useful and included possible options for content, such as the CHW’s biography.

Even at this stage—before writing anything for the brochure—the author-intern considered the culture of the CHW’s clients when deciding what information to include in the CHW’s brochure. For example, one CHW stated that she worked almost exclusively with single mothers who were willing to place a greater amount of trust in the CHW for medical advice, while another said that her clients placed a great emphasis on the family hierarchy and asked for her assistance mostly for English translation during medical visits. Each CHW modified the brochure to give appropriate information to her clients and omit or lessen information on issues clients did not usually encounter.

While establishing a personal connection with the client was a top consideration for the personalized brochures, the translated brochures required even more customization. After finalizing the personalized brochures in English, the author met with the three bilingual CHWs several times to write, review, and edit translations for clients who were not English speakers. The processes for creating the translations were similar; yet, because the general brochure needed to adhere more closely to the marketing identity and legal concerns of the community health center, the CHWs who translated had less freedom of word and phrase choice. Developing the general brochure in English, the author-intern used lay terms and simple phrases, which aided the CHWs greatly in translation. The rule of thumb followed was to stick to widely accepted translations. Because the potential client may not have a translator present when receiving and/or reading the brochure, it needed to be concise and simple for easy comprehension.

Applying similar approaches to the translations, the author-intern recognized the unique elements that each CHW required in their own translated brochures. For example, a CHW who spoke Arabic helped design her brochure in English with the ultimate goal of creating an Arabic translation of it for those of her clients who did not speak English (some of her clients were bilingual and some spoke English as their primary language). The author-intern and CHW worked together to ensure that the CHW was comfortable with the overall persona she presented in the brochure by omitting issues that were sensitive in her culture from both English and Arabic versions. Then, the CHW conducted the final translation from English to Arabic.

While finalizing the general brochure, the CHWs each took prototypes of their personalized brochures to their clients, who provided suggestions and comments for these prototypes, leading to modifications of the personalized brochures to make them more usable for the CHWs. For example, one CHW noticed that her clients kept her brochure on the refrigerator so her contact information could be easily accessible. Because of the design of the brochure, her clients had to re-fold or cut the brochure to make her contact information accessible. Subsequently, the CHW moved these two blocks of information onto the same panel on all brochures.

The context that fosters the relationship between the CHW and her client encourages a personal connection and, thus, the consideration of her own ethos. The specialized brochures for each individual CHW follow a series of conditions of use to build that connection and credibility. First, it was crucial to ensure that the information presented was easily accessible to clients: the CHW translated each brochure into the native language of the client. Second, the very form of a brochure bridges the physical proximity between the CHW and the client, acting metaphorically as a handshake to build trust. As CHWs are not medical experts, they must relate to their clients in other ways to build that trust. CHWs’ linguistic and cultural identification, instead, helps do just that. Lastly, a brochure provides information that lower-income clients may not be able to access from the health center’s website if their Internet access is limited.

Results

Writing a culturally appropriate, individualized brochure for each CHW, the author-intern had to recognize certain traits of the health workers’ clients so she could understand how each brochure would work. While one cannot assume that these brochures work equally for each CHW, they all do work rhetorically: the CHWs’ translations of the brochures reflect the cultural relationships they have with their own clients. For example, two of the CHWs spoke Spanish, but each chose a different approach to translate their brochures as they were from different Spanish-speaking countries: Mexico and the Dominican Republic. For their personalized brochures, each chose to use Spanish words and phrases more appropriate to their respective Spanish-speaking cultures (and, thus, words and phrases they were more comfortable using) to present their personalities. One CHW chose to use informal Spanish, which she said is more widely used in her country and created a friendly persona in writing. The other chose to use formal Spanish because, to her, informal Spanish seemed inappropriate when introducing herself to a new client.

Despite minor changes, all four CHWs said they were very satisfied with their personalized brochures. One said having her own brochure made her feel more professional when she met with clients for the first time. Another CHW commented that she used her brochure to discuss what she could do for a client, and the visual aid of using the brochure seemed to help her clients better define and understand her role as a CHW. For the CHWs, the brochures provide legitimacy for the work they are doing. Working together, the author-intern, health center liaisons, and CHWs accommodated the linguistic and cultural needs of the clients. This collaborative effort illustrates the need for stakeholders to be involved in a network of creating effective health communications for the public.

Discussion

The author-intern situated herself within such a network to understand the rhetorical construction of this discourse community. She benefited as well from experiential learning through classroom-workplace collaborations, which “can be valuable experiences for our students, exposing them to the cultures and activities of the workplace and gradually introducing them to the genres that both arise from and support those cultures and activities” (Blakeslee 189). Such experiences have the potential to help acclimate students to a workplace; however, students need to fully grasp the rhetorical nature of the situation. Preparation in meeting the needs of various communities in epistemic as well as linguistic ways, in part, relies on the student’s challenge to embed herself within a community and her willingness to understand and work with, and within, the genres of that community (Berkenkotter and Huckin).

But the challenge goes beyond trying to “embed” herself into “a community.” There are multiple communities here, beginning with the curricular: (1) the coursework that prefaces (2) the 150-hour internship required of our graduate program; (3) the CHW program and its representatives; (4) the community health workers; and (5) their own clients. The author-intern situates herself among all of these communities, directly or indirectly, and must resituate herself in response to the needs of each. The work is not linear; it is messy, recursive, and disrupts the approaches we tend to instill in our students: here are your new skills, go and use them. The most important skills, however, are to understand that there are too many skills to learn (and teach); that there are processes, not a process, and that there are too many to learn (and teach); and that these processes in themselves are not linear: potential interns will not get a client, apply skills, do the job, and get the grade. Students, therefore, must learn to be rhetorically in tune to discovery and appropriate action.

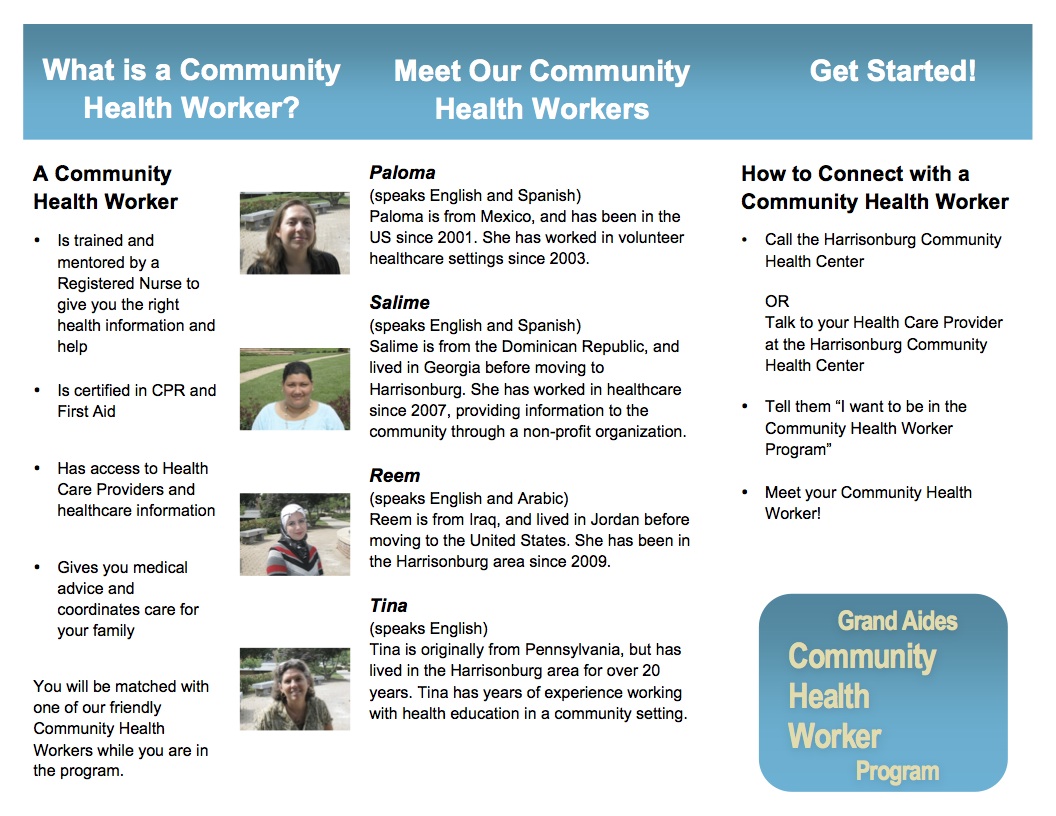

For example, the author-intern, asked to design a brochure, had to learn how to design a brochure as she went, and to design it in the software the CHW program used so that anyone in the office would be able to update or revise the brochure once the author-intern had fulfilled the internship. The reality of small budgets in the workplace—particularly for nonprofits such as the CHW program—drives the need for software that is less cutting-edge than the ones we teach our students to embrace. Further, the author-intern had to understand the needs of the principal client: the CHW program and their identity and mission reflected in the brochures. But as the author-intern began working with the community health workers, she had to understand how each CHW wanted to represent themselves, negotiating with the constraints of: (1) the message and mission of the CHW program; (2) the ethos the CHW wants to present and the ethos the CHW program will allow them to present; (3) the varying translations appropriate for the client’s culture and vernacular; and (4) the clients’ satisfaction that the brochure is actually useful. The author-intern must negotiate each of these elements: How does the usability affect the design? How would translation affect the formatting of the brochure: designing the brochure to be read from left to right in English and Spanish but right to left in Arabic? Do these translations reflect the cultures of not simply, for example, Spanish speakers but of their vernacular-Spanish-speaking nations? Do the vernacular translations effectively serve the identity brand of the CHW program? Do the CHW’s biographical statements—in either English or other respective language—reflect the identity and messages of the CHW program itself? Each of these questions begins with the client, then moves to the CHW, then to the author-intern, who goes to the CHW program for a final say.

For the author-intern, working on this project was as much about learning to understand the genre constraints—of both the community health center and its clients—as it was about communicating information. She learned that understanding the conventions of her own network, through direct interaction with CHWs and community health center officials and indirect contact with the CHW clients, allowed her to provide deliverables to the CHWs that met their needs and the needs of their clients. Working with these various stakeholders, the author–intern produced documents that fulfilled the rhetorical needs of the various situations and their audiences by being responsive to such a recursive approach. This awareness reinforces the need to understand that the workplace, or the classroom, is a recursive system that consists of more than simply a linear process of an employee producing a text for a supervisor or a student producing a text for a teacher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like thank the Harrisonburg Community Health Center, the Community Health Worker Program at Eastern Mennonite University, and the four community health workers for their assistance in this project. They would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful feedback during the revision process.

Endnotes

- This article is especially geared towards programs—both undergraduate and graduate—that are considering the inclusion of an internship course either as an elective or requirement. Preparing students ahead of time to anticipate the challenges they might encounter (such as by learning from the experiences of our own intern) will increase the likelihood that the internship experience is a beneficial one for all parties involved. return

- We describe her here as an “author-intern,” as she is one of the authors of this article—extending her role into yet another community of stakeholders with whom she must also negotiate a number of processes. return

Works Cited

- Berkenkotter, Carol, and Thomas Huckin. Genre Knowledge in Disciplinary Communication. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1995. Print.

- Blakeslee, Ann M. “Bridging the Workplace and the Academy: Teaching Professional Genres through Classroom-Workplace Collaborations. Technical Communication Quarterly 10.2 (2001): 169–92. Print.

- Bosley, Deborah S. “Broadening the Base of a Technical Communication Program: An Industrial/Academic Alliance.” Technical Communication Quarterly 1.1 (1992): 41-56. Print.

- Little, Sherry Burgus. “The Technical Communication Internship: An Application of Experiential Learning Theory.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 7.4: (1993): 423-51.

- Witmer, Anne, Sarena D. Seifer, Leonard Finocchio, Jodi Leslie, and Edward H. O’Neil. “Community Health Workers: Integral Members of the Health Care Work Force.” American Journal of Public Health 83.8 (1995): 1055-58. Print.

Michael J. Klein is director of graduate studies and associate professor of Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication at James Madison University, where he coordinates the graduate internship program. His research interests include the examination of surveillance of the body through medical technology and the media’s role in disseminating scientific and technological information.

Michael J. Klein is director of graduate studies and associate professor of Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication at James Madison University, where he coordinates the graduate internship program. His research interests include the examination of surveillance of the body through medical technology and the media’s role in disseminating scientific and technological information.  Scott Lunsford is assistant professor of Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication at James Madison University. His research explores the intersections of rhetoric and mobility: the implications of discursive and material rhetorics on our experiences in and through various spaces/places.

Scott Lunsford is assistant professor of Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication at James Madison University. His research explores the intersections of rhetoric and mobility: the implications of discursive and material rhetorics on our experiences in and through various spaces/places.  Cindy Chiarello is a graduate of the Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication graduate program at James Madison University, where her research interests included scientific and medical writing for lay audiences, working with non-native English writers and editing for non-native English audiences. She currently works in University Planning at JMU to support planning initiatives and accreditation compliance.

Cindy Chiarello is a graduate of the Writing, Rhetoric and Technical Communication graduate program at James Madison University, where her research interests included scientific and medical writing for lay audiences, working with non-native English writers and editing for non-native English audiences. She currently works in University Planning at JMU to support planning initiatives and accreditation compliance.