Sociotechnical Notemaking: Short-Form to Long-Form Writing Practices

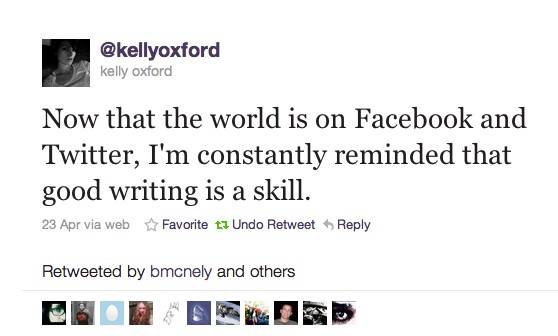

Clive Thompson, contributing writer for the New York Times magazine and columnist for Wired magazine, is keenly interested in emergent literacy practices. He’s no stranger to the field of Rhetoric and Composition, having written an insightful treatment of Andrea Lunsford’s Stanford Study of Writing in a 2009 issue of Wired (“On the New Literacy”). In the January 2011 issue of Wired, Thompson explores short-form writing practices—“text messages, tweets, and status updates” (“Tweets and Texts”)—invoking what Jeff Jarvis calls the distraction trope: “We’re often told that the internet has destroyed people’s patience for long, well-thought-out arguments” (“Tweets and Texts”). But Thompson has a contrary response to the distraction trope: a “torrent of short-form thinking is actually a catalyst for more long-form meditation” (“Tweets and Texts”). Thompson argues that short-form writing actually fosters longer, more considered explorations that sometimes evolve into substantial, formal prose.

Thompson cites Anil Dash, an influential blogger and technology advisor. He quotes Dash as saying, “I save the little stuff for Twitter and blog only when I have something big to say” (“Tweets and Texts”). Shortly after Thompson’s column appeared online, Dash responded with a lengthy blog post, arguing that “some ideas are bigger than 140 characters. In fact, most good ideas are” (“If You Didn’t Blog It”). Dash contends that “individual ideas in those flow-based media [such as Twitter and Facebook] don’t have enough substance for a meaningful conversation to accrete around them” (“If You Didn’t Blog It”). He suggests instead that blog posts (and other, longer-form media) enable a kind of ideational synthesis, where the persistence and stability of blog posts, in contrast to sometimes ephemeral flow-based media, foster a sense of permanence—ideas and spaces to which people may link and return to again and again. Despite his arguments in favor of blogging as a persistent medium for substantial ideas, Dash doesn’t seem to deny Thompson’s claim concerning the inventional usefulness of short-form writing.

Nicholas Carr does, however. Author of The Shallows and frequent proponent of the distraction trope (see, for example, “Is Google Making us Stupid?”), Carr publicly joined the discussion shortly after Dash, suggesting that “Short is the new long.” One of Carr’s contributions to the debate concerns the definition of what constitutes long-form writing, where what once would have been a “middle take” is now viewed as a “long take” (“Short is The New Long”). Carr also confronts Thompson’s primary claim, arguing that he “never describes precisely how or why this alleged catalytic action, through which the swirl of info-bits deepens our engagement with longer-form material, plays out” (“Short is The New Long”). Carr’s complaint is one of evidence and validity; seeing none, he suggests that Thompson’s argument amounts to little more than a “hunch.”1

Thompson’s argument is ultimately about invention and heuristics, about the affordances of social software for getting people to write, and for those same people to think and know through their writing. In this article, I reframe these recent public debates about emergent literacy practices by situating the movement of short-form to long-form writing work within the disciplinary milieu of Rhetoric and Composition. More importantly, I provide findings from an ethnographic study of media researchers that illustrate how Thompson’s claim is significantly more than a “hunch,” that knowledge workers actually use social software in heuristic and inventional ways, in a kind of sociotechnical notemaking.

Reframing the Debate

To scholars in the field of Rhetoric and Composition, Thompson’s “hunch” has plenty of evidence: at least 50 years of research from a variety of methodological perspectives that support the notion that writing is explicitly epistemic.2 We make meaning through our writing; sometimes short-form writing acts as a catalyst for longer-form writing. This is less a revelation than the sudden realization of such practices on a massive scale, thanks in part to social software and text messaging. But many of these newly visible practices have been observed, documented, and analyzed by Rhetoric and Composition scholars for years—in classrooms, workplaces, and experimental studies. Carr’s focus is trained in the opposite direction of Thompson’s claim—on consumption practices rather than production, what writing actually does for writers themselves.

Carr’s critique of Thompson’s primary claim hinges on a wayward assumption about the nature of the claim itself. Carr argues that “it’s a fallacy to assume that the availability of long-form works means that our reading and viewing of long-form works is increasing” (“Short is The New Long”). In following this argument, Carr moves away from Thompson’s claim, which has far less to do with consumption patterns than it does with illustrating how long-form public writing work may have gotten its start through short-form inventional practices. Put more simply: for Carr, the debate is about reading;3 for Thompson, the debate is about significant public writing work, extending a point made in his 2009 piece on emergent literacies: “Before the Internet came along, most Americans never wrote anything, ever, that wasn’t a school assignment” (“On the New Literacy”). It’s not simply about consumption; it’s about the act of writing and publishing, about knowing and being in the world as one who writes.

This aspect of the debate is well-worn ground for scholars and practitioners in Rhetoric and Composition. Writing and rhetoric are productive acts—to study writing is to study how people come to know, and how they share and negotiate what they know. To write, to speak, to act in the world as rhetorical practice (in short forms and long forms) is to make meaning, to situate oneself—to think, make, and do. Robert Scott, Barry Brummett, Michael Leff, James Berlin, and many other prominent scholars have argued cogently and from a variety of perspectives that rhetoric is indeed epistemic, that rhetoric creates truth rather than simply revealing extant truths. A common thread woven into germinal Rhetoric and Composition scholarship is the notion that writing and rhetorical practice are ways of knowing and being.4

Writing is an increasingly pervasive human activity, a crucial, everyday aspect of making meaning in the world. As Andrea Lunsford notes in Thompson’s 2009 piece, “I think we’re in the midst of a literacy revolution the likes of which we haven’t seen since Greek civilization” (“On the New Literacy”). We write constantly—with pencils, on mobile devices, in text editors, in emails and documents, and increasingly, through social software. These writing activities—however ephemeral, fleeting, or seemingly insignificant—are, in the main, “epistemologically productive” (Grabill and Hart-Davidson 1). Again, this is nothing new for disciplinary insiders. In 1977, Janet Emig argued that “writing represents a unique mode of learning,” primarily because “writing as process-and-product possesses a cluster of attributes that correspond uniquely to certain powerful learning strategies” (122). Based partly on detailed studies of the writing activities of twelfth graders—note-taking, planning, revising, etc.—Emig suggests that “writing involves the fullest possible functioning of the brain” (125).5

In addition to these perspectives on writing as an epistemic activity, certain writing practices are likewise explicitly heuristic and inventional. Once again, for Rhetoric and Composition scholars, this is old news. In 1980, James Berlin and Robert Inkster argued that the cognitive mechanisms of classical invention, such as Aristotle’s topoi, constitute heuristic processes.6 Certain practices—outlining, sketching, underlining, writing in margins—are often heuristic and inventional, a way of formulating meaning through intentional and directed informal writing that often leads to other, more formal writing work. The field of Rhetoric and Composition has a rich history of studying this informal, transitory, often ephemeral writing work that supports more formalized modes of production. These are practices of planning and thinking about problems through informal writing work—small but significant inventional, heuristic, and epistemic practices.

Sociotechnical Notemaking and the Read/Write Web

For Bonnie Nardi and Vicki O’Day, the term “sociotechnical networks” reflects the fact that technological tools carry social meaning that becomes embedded in the technologies themselves (21). Sociotechnical networks evoke the complexity of much contemporary online communication; they describe intricate relations among individuals and groups through enabling technologies such as social software. Clay Spinuzzi notes that sociotechnical networks are significantly instantiated in writing and rhetoric. Indeed, the sociotechnical networks of contemporary distributed work create situations in which “rhetoric becomes an essential area of expertise” because “we are all potentially in contact with each other, across organizational and disciplinary lines” (Spinuzzi 272). We have the potential, via social software and other enabling technologies of distributed work and education, to think out loud and be immediately heard by others through our writing.

Christina Haas defines “notemaking” as “the creation and manipulation of planning notes prior to, and occasionally during, writing” (98). In her experimental studies of writers’ planning processes, she argues that “[n]otes are at once the output of planning, a strategy for cognitive monitoring, and a writer’s first visible attempts at language” (98, emphasis added). Haas discusses the inventional and heuristic benefits of notemaking, suggesting that these practices created infrastructures of external memory and cognitive monitoring while aiding writers in developing conceptual structures that “provide a way to work out relationships between ideas and to develop” more complex arguments (98). This is short-form writing that is epistemologically productive. What if such writing work were enacted within sociotechnical networks, rather than individually or in small groups? What if notemaking was a public, interactive practice?

In his discussion of the distraction trope, Jeff Jarvis notes that Twitter did distract him at times during the writing of his most recent book. But he also argues that Twitter has unique benefits for long-form writing work: “it helped with my writing that I always had ready researchers and editors, friends willing to help when I got stuck or needed inspiration” (“The Distraction Trope”). Jarvis, I argue, was engaged in sociotechnical notemaking during such periods, using informal, networked, short-form writing work in digital publics as a heuristic and inventional practice leading to the generation of more formal prose.

There are unique benefits to public notemaking activities, where one’s thoughts and ideas, however small or ill-formed, are enmeshed in networks of potentially interested collaborators who can buttress cognitive monitoring and aid invention. When notemaking is shared with such fellow travelers, when these practices are viewable by potentially everyone, across different disciplinary and professional domains, how much more can 140 characters act heuristically, as a pivot for social interaction (Morville) and agonistic exchange, where ideas can be tested and developed, and where invention might flourish?7

Facebook, Twitter, and other forms of social software are about consumption and production, about dialectic interaction on the read/write web. It’s no wonder short-form writing in sociotechnical networks is epistemologically productive, often leading to richer, longer-form writing work. Savvy writers might intentionally deploy sociotechnical notemaking as a powerful heuristic strategy for moving from short-form to long-form writing practices. Sociotechnical notemaking may therefore be defined as short-form writing work that is typically enacted informally via the enabling technologies of social software, with explicit heuristic, inventional, and epistemological implications. In the final section, I discuss such implications in professional practice, among knowledge workers who specifically deployed sociotechnical notemaking in conjunction with more formal modes of writing.

More than a Hunch

For almost nine months—from July, 2010 through March, 2011—I collected rich, granular data for an ethnographic study of professionals at a media research firm, following their work in planning, conducting, and publicly disseminating findings from behavioral studies of consumer privacy issues online.8 I had unique access to my participants’ communication practices—online and face-to-face, formal and informal, in social software and drafts of organizational deliverables. While a detailed discussion of this study is beyond the scope of this article, one of my findings clearly indicates that short-form writing work and sociotechnical notemaking did indeed act in heuristic and inventional ways for my participants, leading directly into longer-form professional deliverables. Below, I detail one example of the kinds of short-form to long-form sociotechnical notemaking practices that I observed repeatedly during my study.

As the lead project manager for the consumer research sessions described above, Jenn was responsible for leading data collection, and for generating a significant portion of the formal, organizational prose that was eventually disseminated. Jenn worked closely with Mike, the firm’s director, and Michelle, the firm’s communication specialist, throughout the project. During my study, these three were constantly in contact with one another: in the office; at lunches and meetings; and via email, Facebook, Twitter, and text messages. Through social software in particular, they exchanged ideas with one another, while seeding and testing preliminary findings via short-form writing work with broader public audiences.

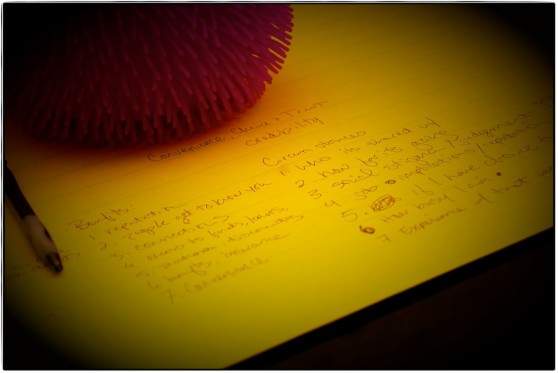

During one week in late September, the firm conducted four research sessions with small groups of consumers—one each day for about three hours. These sessions were intensive, with Jenn and Michelle using a variety of creativity techniques to yield insights from consumers about privacy issues online. After the last session ended, Jenn and Michelle uploaded select photos of their conference room to Facebook, so that other team members, friends, and professional contacts might see some of the playful artifacts they used in their sessions (as in the photo above).

Interestingly, these Facebook posts—images accompanied by short, explanatory text—generated much discussion about the project among team members and contacts beyond the firm. The following day, Jenn, Michelle, and Mike arranged a debrief meeting to discuss initial insights gleaned from the research sessions. While the team gathered informally in the office before the meeting, talk turned to the Facebook posts as team members revisited the upbeat mood from the previous day. This prompted a move to a local restaurant instead of the firm’s conference room, where they spent their first ten minutes together debriefing through individual notemaking activities—writing in silence, with pen and paper, the most important insights that each gleaned from a week of sessions. Many of these insights would later be made into brief, arresting encapsulations of their findings, things like “learned helplessness” and “transparency is the new green.”

During the weeks that followed, these ideas were repeatedly expressed via short-form writing work and informal face-to-face communication, as Jenn worked through her detailed analysis of the data. Mike and Michelle periodically posted these ideas on Facebook and Twitter, garnering interaction from friends, clients, and industry contacts. Doing so, they engaged in dialogue with important influencers, adding weight to their developing ideas about how they would report and position their findings. Jenn’s formal writing work could be traced from Facebook, to pen and paper notemaking, to face-to-face discussions in the office, via email and social software, all the way through her qualitative data analysis application, outlines, coding spreadsheets, presentation software, and text editors.

Each link in the chain of Jenn’s writing activity matters. Some (such as notemaking, Facebook posts, and tweets) were strategically heuristic and inventional, while all were epistemologically productive—they helped her move from planning to dissemination, from informal short-forms to professional long-forms. A crucial link in that chain of literate activity was sociotechnical notemaking—the testing of ideas in digital publics, initial visible attempts at formulating complex, long-form writing work.

Findings from this study indicate that Thompson’s idea—that public, short-form writing work may often act as a catalyst for more considered long-form prose—is much more than a hunch. Indeed, sociotechnical notemaking is short-form writing work that is explicitly heuristic, inventional, and epistemologically productive.

Endnotes

- Recent books by Dennis Baron and Sherry Turkle provide considerably more nuance and context for these and similar ongoing debates. return

- Writing is epistemic, in fact, in many different genres and media—short, long, and in-between. return

- This is because, for Carr, it appears that reading is the primary means through which one achieves engagement, a notion that’s not defined or quantified in any way in his blog post. Implicit in Carr’s argument is the corresponding assumption that writing, especially in short forms, does not constitute engagement. return

- Indeed, for Barry Brummett rhetoric and writing are epistemic in an ontological sense—“all of what people do is in some way rhetorically shaped and, in its turn, rhetorically influential on others” (Brummett 4). return

- Janice Lauer’s germinal work (“Writing as Inquiry,” “Composition Studies”) similarly explores writing as enacting complex languaging and learning processes, seeing writing as inherently epistemic. return

- Berlin and Inkster argue that a heuristic “may be defined as a systematic way of moving toward satisfactory control of an ambiguous or problematic situation, but not to a single solution” (3). return

- Jeff Atwood’s Coding Horror provides yet another salient example, in a blog post titled “How to Write Without Writing.” Atwood sees his Stack Overflow site, a collaboratively edited question-and-answer repository for professional programmers, as providing “lightweight, focused, fun-size units of writing” designed to get programmers thinking out loud, through their writing, while improving communication skills in the process (“How to Write”). This is writing as discovery, where professionals are engaged in often short, “fun-size” writing activities within a sociotechnical network as a way to improve more formal modes of communication—programming, documentation, reports. return

- This study was approved under Ball State University’s Institutional Review Board, #180393-1, “Exploring Ideation Sessions as Knowledge Work,” 16 July, 2010. As an ethnographic workplace study, my data consisted of site observations (both scheduled and impromptu) and corresponding field notes; interviews with research participants; audio recordings of work sessions and meetings; photographs; and artifact collection and analysis. The total data set is comprehensive, relative to the specific activities of my research participants working through the arc of consumer research sessions described herein.

I collected over 150 participant-produced artifacts, recorded over 60 hours of meetings and interviews (impromptu and official), conducted over 20 semi-structured interviews, took over 400 photographs, and traced my participants’ communication practices through two different social networks, collecting almost 2,400 tweets while simultaneously monitoring several hundred Facebook status updates from my three primary participants (out of seven total). Data analysis of the full corpus is ongoing; findings for the social software sample of this data (discussed in this article) were generated via process and descriptive coding, analytic memos, and theming of those specific artifacts (tweets and Facebook updates) within the larger context of my observations, field notes, and semi-structured interviews. return

Works Cited

- Atwood, Jeff. “How to Write without Writing.” Coding Horror. Coding Horror, 4 Feb. 2011. Web. 5 Feb. 2011.

- Baron, Dennis. A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

- Berlin, James. “Contemporary Composition: The Major Pedagogical Theories.” College English 44.8 (1982): 765–777. Print.

- Berlin, James, and Robert Inkster. “Current-Traditional Rhetoric: Paradigm and Practice.” Freshman English News 8.3 (1980): 1–14. Print.

- Brummett, Barry. “Three Meanings of Epistemic Rhetoric.” Speech Communication Association Annual Convention. San Antonio, TX. Nov. 1979. Conference Presentation.

- Carr, Nicholas. “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” The Atlantic. Atlantic Mag., July/Aug. 2008. Web. 28 Mar. 2011.

- —. The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains. New York: Norton, 2010. Print.

- —. “Short is the New Long.” Rough Type. Rough Type, 16 Jan. 2011. Web. 16 Jan. 2011.

- Dash, Anil. “If You Didn’t Blog It, It Didn’t Happen.” Anil Dash: A Blog about Making Culture. Anil Dash, 4 Jan. 2011. Web. 6 Jan. 2011.

- Emig, Janet. “Writing as a Mode of Learning.” College Composition and Communication 28.2 (1977): 122–128. Print.

- Grabill, Jeffery, and William Hart-Davidson. “Understanding and Supporting Knowledge Work in Everyday Life.” Language At Work (2010): n. pag. Web. 28 Dec. 2010.

- Haas, Christina. Writing Technology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1996. Print.

- Jarvis, Jeff. “The Distraction Trope.” BuzzMachine. BuzzMachine, 24 Feb. 2011. Web. 8 Mar. 2011.

- Lauer, Janice. “Composition Studies: Dappled Discipline.” Rhetoric Review 3.1 (1984): 20–29. Print.

- —. “Writing as Inquiry: Some Questions for Teachers.” College Composition and Communication 33.1 (1982): 89–93. Print.

- Leff, Michael. “In Search of Ariadne’s Thread: A Review of the Recent Literature on Rhetorical Theory.” Central States Speech Journal 29 (1978): 73–91. Print.

- Morville, Peter. Ambient Findability. Sebastapol, CA: O’Reilly, 2005. Print.

- Nardi, Bonnie, and Vicki O’Day. Information Ecologies: Using Technology with Heart. Cambridge: MIT UP, 1999. Print.

- Scott, Robert. “On Viewing Rhetoric as Epistemic.” Central States Speech Journal 18 (1967): 9–16. Print.

- Spinuzzi, Clay. “Guest Editor’s Introduction: Technical Communication in the Age of Distributed Work.” Technical Communication Quarterly 16.3 (2007): 265–277. Print.

- Thompson, Clive. “On the New Literacy.” Wired. Wired Mag., 24 Aug. 2009. Web. 28 Mar. 2011.

- —. “Clive Thompson on How Tweets and Texts Nurture In-Depth Analysis.” Wired. Wired Mag., 27 Dec. 2010. Web. 28 Dec. 2010.

- Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2011. Print.